Scott Lang and JoAnn Seagren, Chicago - MEET THE COLLECTOR Series Part Fifty-Six

I found out about Scott Lang and his wife JoAnn Seagren earlier this year, then heard more about their collection through Deb Kerr from Intuit and through a short video shared through the 2020 Intersect Chicago Art Fair. Scott shares great stories of how he came to this art alongside him and JoAnn sharing how they curate outsider works alongside contemporary art works in their home. Read on to find out more from this couple in part fifty-six of my ‘Meet the Collector’ series. Grab a cup of your favourite hot drink as it’s a long one!

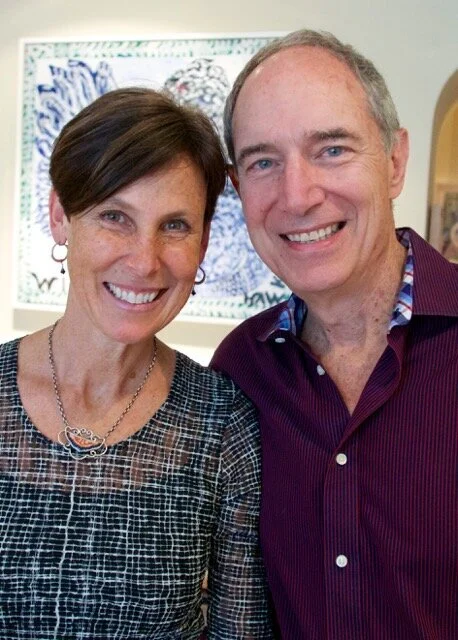

Scott Lang and JoAnn Seagren in front of William Hawkins

Jennifer: When did your interests in the outsider art field begin?

Scott: Back in the late 1970s for me. JoAnn’s interest started after we met, after she saw some of the outsider works I had been collecting. The collection has really grown since then.

JoAnn: Scott and I have been together for eight years and married for the last three. I had no knowledge of outsider art whatsoever until I met Scott. In his apartment, at the time we met, there were stacks of paintings on the floor and paintings and on the walls… well not just paintings, but all kinds of artforms, so he was clearly a collector - that was apparent to me right away, but I had not been a collector. We're a little bit different that way.

Scott: Just so you get the full context, JoAnn is very well traveled, and she has collected things from around the world. They tend to be works of indigenous and primitive people – actually self-taught artists. So those things happen to go extremely well with outsider art and with contemporary art. I mean they're beautiful things and they're not made by academically trained artists; so they have a similar feel to the outsider artists I was collecting.

I remember vividly when I bought my first work by an outsider or self-taught artist - it was back in the 70’s in Washington, D.C., where I lived at that time. I liked art, but I wasn't a collector or anything like that. I was a young government lawyer with no money for art collecting. One day, while visiting the Barbara Fendrick Gallery in Georgetown, I saw a work of art resting on the floor, just leaning up against the wall. It was about a foot and a half high and maybe two feet wide. It was carved from wood and very colorfully painted, a relief made from painted wood. I asked the gallery owner, ”What's that?” And she said, “Oh, that's by a ‘folk artist’ named Elijah Pierce.” She didn't say by an outsider artist, because “outsider” was not used then to describe the genre. The title of the work was “Pickin’ Cotton.” She pointed to various little scenes within the work. There were women slaves picking cotton in a field in the upper left quadrant, a beaming face of God smiling down beneficently like the sun in the upper right, and below were several small colorful scenes. One scene was of Uncle Sam promising a newly freed slave couple a mule and forty acres, but right behind Uncle Sam was a white man whipping a slave bloody, and there were a lot of other scenes depicting the meanness of slavery and the false promises of emancipation. I really liked the work, and I wanted to know more about the artist.

She told me the artist said he’d been visited by God in a dream or something when he was young and living in in the Deep South, and God told him to carve and paint wood, which he did. Later, during what we now call The Great Migration, he joined the millions of Black Americans moving from the South to the North and West to escape the Jim Crow laws and the poverty and depravity of being a free black person in the Jim Crow South. Elijah Pierce’s parents were, in fact, freed slaves. She told me he had settled in Columbus, Ohio, where he became a barber, continued to carve and paint wood, and he became a preacher of sorts. I asked how much the work cost. She said $750, which I could afford, so I bought it. I didn't know any more than what I just told you, but I will say that the colorful background of the artist made it exciting.

She showed me other works by Elijah Pierce, one called “Leroy Brown,” which I soon regretted I had not bought, but it was enough to buy just one of his works at the time. I asked where she got the works, and she said a young man in New York City was the artist’s dealer outside of Columbus, Ohio. His name was Jeffrey Wolf. Today he is the leading producer and director of documentary films on the lives of celebrated outsider artists, like James Castle, William Traylor, and others. So, I went up to New York, which I did often in those days, and visited Jeffrey Wolf and his wife in their apartment where I saw many more works by Pierce. I may have bought one, I can’t recall. Jeff and his wife Jeanie and I became friends and have remained good friends ever since. (That’s the thing about outsider art collecting, it’s still such a small subculture, so when you meet someone new in it and discover you have something uniquely interesting in common, a friendship instinctively grows around that. I think that’s true of collectors of almost any small art genre.) A couple of years later, in 1982, there was a museum show called Black Folk Art in America at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C., which you may have heard of, and I was asked to loan “Pickin’ Cotton” to the exhibition, which of course I did.

Jennifer: Yes, many people say that this is their favorite exhibition in this field, and it created major awareness.

Scott: It was an amazing exhibition. I went to it without any idea what to expect. I met Elijah Pierce. He signed my catalog. He was about 90 years old, very thin and well over six feet tall – a tall old skinny guy. I found out he also had a dealer in Philadelphia, named Janet Fleischer, whose name you might know.

Jennifer: Yes, Fleisher Ollman Gallery in Philadelphia.

Scott: Yes, exactly. It’s still one of the leading galleries of outsider art in the U.S. So, Fleischer Ollman had also loaned works by Elijah Pierce to the Corcoran show, and I actually bought a few of those works and still have them. One is called, “Kids Don’t Care about Race,” with a black boy and white boy sitting shoulder to shoulder on a bench, almost hugging each other, and there is a tiny black-and-white Dalmatian dog below them, separately carved and collaged onto the relief at their feet. The message: color of skin does not matter. That work was later loaned to an exhibit at the Renwick Gallery in D.C. I also bought a few fabulous little carved animals by Pierce from Janet Fleischer out of the Corcoran show. So that’s how it all started for me. It was not an investment or a commitment. I just liked the work and fortunately I could afford it, because it was really inexpensive, and fortunately the work had real merit, more than I understood at the time. Today (January 2021), a large selection of Elijah Pierce works are on display in a solo exhibition at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, a very prestigious museum, and they will be there through January 2022. I believe this is the first solo exhibition of an outsider artist at the Barnes. For outsider art collectors, it’s kind of mind-blowing when you see that happen. But events like that are beginning to happen more frequently for outsider artists.

Jennifer: How many pieces, do you think, are in your collection now, and quite obviously it is on the walls of your home, but is it anywhere else?

Scott: There are no more than a handful of pieces in my office, as we don’t have room for all of them in our apartment, but we also collect contemporary artists. It’s not all outsider art. We haven’t counted, but we probably have around 150 works or something like that altogether. Some of them are small and some are large. We have some very inexpensive works and recently added some rather expensive works. More recently, the mainstream art world has started paying serious attention to some of the more celebrated outsider artists, and that has been driving the prices higher. That’s not a bad thing, though, because there are a lot more trained eyes looking at outsider art today and realizing there is really some great work there and more to be discovered. And even though prices have risen, most high-quality outsider art is still very inexpensive compared to works of trained artists with major galleries sponsoring them and major art critics writing them up. As outsider works become appreciated by mainstream collectors, that helps collectors of outsider art like JoAnn and me, because it gives us the courage to keep collecting, knowing that there is a growing market for some of the things we own and possibly even a home in mainstream museums for some of the best of them. Mainstream recognition helps the outsider and self-taught artists, too, because as they become more valuable and more recognized, galleries and museums become more interested, more works get discovered, acquired and exhibited, and more and more mainstream collectors take notice and become involved with the works. The genre gains in importance. Someday there may be very little distinction between great outsider and great mainstream artworks in museums and in galleries in terms of their value, and that could be a good thing, as long as outsider artists can still maintain their status and appeal as a category, as a genre, whatever that appeal is. We think it’s mainly their unique backstories that differentiate them as a group from mainstream artists and, frankly, as of now, their lack of strong sponsorship in the leading galleries and museums and art publications also differentiates them, but that is already shifting.

Jennifer: Definitely. So, I know that you collect contemporary art, alongside outsider art, so how do you feel that the two blend together?

Scott: I think it's hard to make a generalization about that. For us, we like things that are beautiful and unexpected, challenging but not unsettling or grotesque. I think our personal taste sort of blends together the outsider and mainstream art we collect, more than that they necessarily would go together. But it's very interesting to see. Like we have a James Castle “construction” of a coat and a vest made of found carboard and sewing threads, and it’s on a stand next to a beautiful triptych work-on-paper by Jasper Johns called “Voice 2” from the 80’s. Okay, now you wouldn't necessarily do that, but I guarantee you when you come into our living room and you see them together, you realize that those things really do go together. They speak to each other. “Voice 2,” with its abstracted letters and numbers and its really painterly abstract background hanging next to Castle’s small “construction” of a coat and separate vest with collaged square paper buttons, dangling string, and abstracted wash on it that Castle drew using a mix of stove soot and his own saliva, it’s not easy to say one is better than the other. But Castle, unlike Johns, not only had no training, he had no normal art supplies. He was limited to whatever materials came into the remote rural homestead where he lived. It's interesting to see the similar mixing of colors, the beautiful and similar sensibility of the two artists, and the way that their works, coming from very different cultural backgrounds, blend so well with each other, neither one better than the other. It may be just our visual integration of the two together, but others seem to feel it the same way.

Also, in our home we have works by the “Chicago Imagists,” like Roger Brown, Ed Paschke, Christina Ramburg, Gladys Nilsson, Ray Yoshida, Don Baum and others. These artists, many of them still in their 20’s, were among the earliest collectors of outsider artists in Chicago and elsewhere - so you have an obvious connection there between mainstream and outsider art, one that makes art history sense for us. When we have visitors, they can understand a little bit more about outsider artists when they realize that some highly regarded trained artists value outsider artists and buy their works and have even borrowed from their works. For example, you can see some obvious shared influences between Roger Brown and Joseph Yoakum, one of Chicago’s greatest outsider artists. Some of Roger Brown’s shrubs in a painting we own called “Pasadena Garden Residence” look very similar to bushes in some of Joseph Yoakum’s works, in terms of their shape, deep green color, and so on, and so do some of their skies. It brings out a connection, or “hinge,” as I like to call it, between the Chicago Imagists and Chicago outsider artists, which is why we have the two artists’ works hanging in sight of each other in our dining room. It’s no accident that Roger Brown lined the walls of his bedroom with Joseph Yoakum drawings.

The other thing is that great art is great art. And you can put great art of one genre next to great art of another genre without taking much of anything away from either, instead often reinforcing the worthiness of each. You won't notice anything jarring about it, because your eyes go from one great visual experience to another. Trained artists have, you know, I wouldn't call them necessarily rules, but they have techniques and disciplines they’ve been taught to use, and they are usually pretty well educated and integrated into the mainstream culture. Outsider artists don't have such techniques or disciplines, and they have very different influences. So, what the outsider artists are producing is just coming straight from inside, which is really remarkable. You know, to think of a guy like James Castle, who was deaf and mute… to think that he could come up with so many profoundly sensitive drawings and three dimensional constructions and graphic designs and books of his drawings using only found material, and that so many of his works are incredibly contemporary and anticipated some of the great contemporary artists of the 20th Century who came after him, even including Johns and Warhol – to me, that work becomes just as beautiful and important as the contemporary masters. People who visit us and don’t know who James Castle is think he must be a very important artist, because his work holds up so well next to Jasper Johns, perhaps the world’s greatest living contemporary artists. The truth is, Castle is an equally versatile and talented artist, even though he never had an art lesson, lived a sensory-deprived life in rural Idaho where he had very little exposure to the mainstream culture, couldn’t read or write, and had none of the usual resources for making art. So we don’t see a distinction aesthetically, and we notice that our friends don’t either.

James Castle’s “Untitled” (white Bird construction), an 18 page book of his stove soot and saliva miniature drawings and three larger drawings of the same medium

Jennifer: You mentioned the Chicago Imagists there, and I know we talked about it the other day, but for the purpose of this interview and for people that might not know, can you just say who the Chicago Imagists are?

Scott: I'll give you my understanding. There was a group of young artists and their teachers at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago in the mid-to-late 60’s, who viewed the mainstream art world at that time, which was largely dominated by the abstract expressionists of New York and by the emerging pop artists on both coasts, as something they did not want to be a part of. Kind of a “been there, done that” feeling, I suppose. So they started exploring and going back to physical images including a lot of comic book imagery, non-serious, non-sensical in-your-face kind of stuff, sometimes overtly sexual, mocking the self-importance of abstract expressionists and pop artists at that time. When six of them displayed their works together in a joint exhibition at the Hyde Park Art Center in Chicago in the late 60’s, they called themselves “The Hairy Who,” a made-up name that stuck and got them some national attention. A lot of their work was really tongue-in-cheek, poking fun, sexually kinky. It was considered crazy at the time, but today looking back, it seems original, fun and very beautiful, very professionally executed. Last year the Art Institute curated a retrospective exhibit of those early works, and it drew rave reviews. The first Hairy Who group show in Chicago, put on by museum curator Don Baum, was successful and was followed by another in Chicago and a third in San Francisco, when their works were still selling for next to nothing… only a few hundred dollars each. Later on, the six Hairy Who artists, together with some their contemporaries and near contemporaries like Ed Pashke, and professors from the School of the Art Institute, and they came to be collectively known as the “Chicago Imagists,” because of the quirky representational content of their work and their Chicago, mostly Art Institute, roots. Today their works are selling for hundreds of thousands of dollars and may soon go beyond that.

As the story goes, these School of the Art Institute artists were encouraged by their teachers to find art on the streets, art by untrained and anonymous artists, in flea markets and junk shops - Chicago had quite a few. I believe this is how Joseph Yoakum, Lee Godie, William Dawson and other Chicago outsider artists were discovered, befriended and then collected by several of the Chicago Imagists in the 60’s, 70’s and afterwards, and by a few Chicago gallerists like Carl Hammer early on. Jim Nutt, one of the most celebrated of the Chicago Imagists, became a major collector of outsider artists, not only the Chicago outsiders, but also works by others including Martin Ramirez, a self-taught Mexican American artist who was in a California mental institution most of his adult life, where he created some of the most profound artwork of the 20th Century from crude paper and materials he was given to work with by the institution’s personnel. But the Imagists mostly collected Chicago outsider artists, much of which remains in their personal collections today.

Jennifer: Thanks. So can you tell us a bit about your backgrounds?

Scott: Well my background… I grew up in Kankakee, Illinois, a small town downstate from Chicago, and I went to college and law school out east, a far cry from Kankakee. After law school, I wound up moving to Washington, D.C., to take a job with the Environmental Defense Fund, one of the first public interest law firms. After that, during the OPEC oil embargo, I went to work at a federal agency that later became the U.S. Department of Energy, where I headed litigation involving the U.S. Government and the major oil companies who were being regulated for the first time by the government. After that I went into private law practice at a large D.C. law firm, which, when it was moving into a new office building, had the foresight, to set aside considerable funds to start a contemporary art collection. I headed up the works on paper collection effort, which gave me some great exposure to the world of art galleries and dealers and appreciation for contemporary art in general. In the mid-80’s, I was invited to return to Chicago to open an investment banking practice inside a brokerage firm owned by a family member. Today, I’m an investment banker in a boutique Chicago firm, called City Capital Advisors, working with middle market and smaller businesses, which I still love.

JoAnn: I come from Southern California, where I grew up and went to college at USC. I have always loved art, and I have a couple of reasons for that. One was the Tutankhamen exhibition that came to Los Angeles. I think a lot of people credit that as their first really big exhibition that sold tickets in advance to sellout crowds and all of that. And it made a huge impression on me - I was in middle school and I bought a poster of Tutankhamen on a canoe that I kept and hung on the wall of my college dorm room. Then, in college I went to Spain for a semester and signed up for an art class in the Prado Museum. That was a really transformational moment, where I started to really look at art differently, and I started going back to the museum twice a week to explore just a few paintings at a time, and I really tried to understand and get into the artists head and learn the history behind them. That was just transformational for me.

Currently, I'm a managing director of a boutique investment and wealth management firm, called JAG Capital Management, that advises and invests capital for high net worth individuals and family offices. But art continues to enrich everything I do. Also, with the clients I work with, it's really surprising how much art brings us together. And I think Scott and I have found that when we're meeting new people for the first time, there's something about art that deepens relationships and is really special. The final thing I'll say is that, as my kids have gotten to know Scott these last eight years that we’ve been together, they've started appreciating art in a deeper way. Of course, they've always enjoyed going to museums and seeing the art there, but seeing it in our home, seeing it through Scott's eyes, and learning about the unique backgrounds of both the relatively unknown outsiders and the highly trained and highly recognized mainstream artists, they've started appreciating art differently and a lot more. A great example is from a few years ago when my daughter was home visiting from the East Coast for the holidays, a friend of hers from college decided to stop here for a night and my daughter greeted her at the door. Before even showing her to her room, she said, “I want to show you the art,” and proceeded to give her friend this whole art tour in which she related all the artists’ stories. And the interesting thing is, going back to outsider art, the reason I think she retained all of that information and wanted to share it is because the stories of these outsider artists are so unusual, improbable, and often heroic. I think many artists go through hardships, including trained artists, because you know it's hard to make a living as an artist. But outsider artists’ stories are even more poignant, and those were the things that she was talking about. That's one of the reasons that Scott and I both love outsider art so much, because the artists’ stories are so moving and so unusual, and they make the art more interesting, personal and authentic.

Jennifer: So with that in mind, do you both have a favorite artist and why?

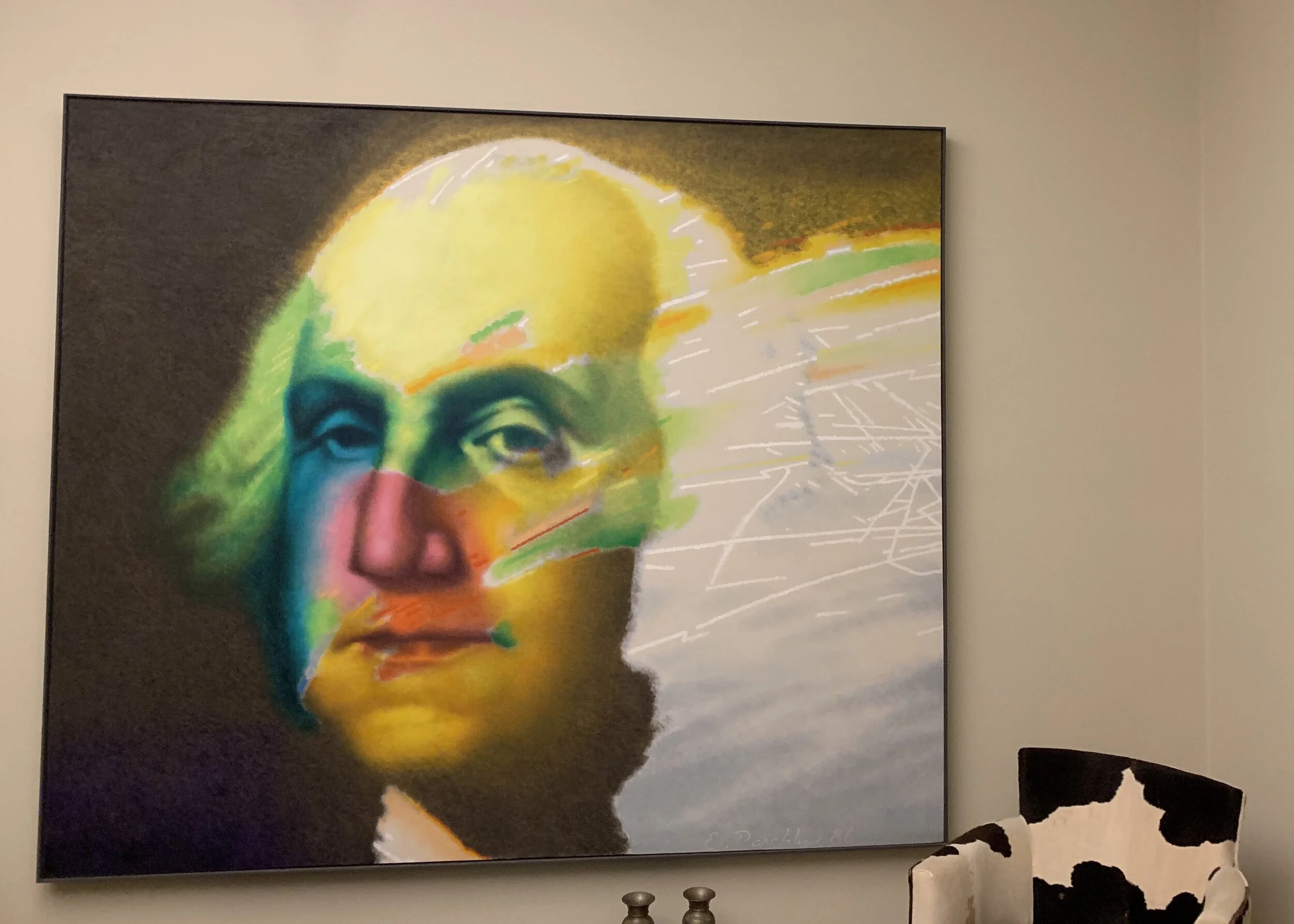

Scott: I mean with contemporary artists, we like many artists we can't afford, obviously, so we’ve now pretty much limited ourselves to collecting works by the Chicago Imagists. But if you’re asking just about what we own and live with, in terms of contemporary art, we have a Robert Longo diptych drawing from his “Men in the Cities” series that is one of our favorite works, which I bought back in the 80’s. And we have an iconic Ed Paschke painting of George Washington that I never tire of looking at. He’s not only magnificent, but mysterious and highly colorful… he just has a big presence. But in terms of outsider art, that's too hard… that question’s not fair!

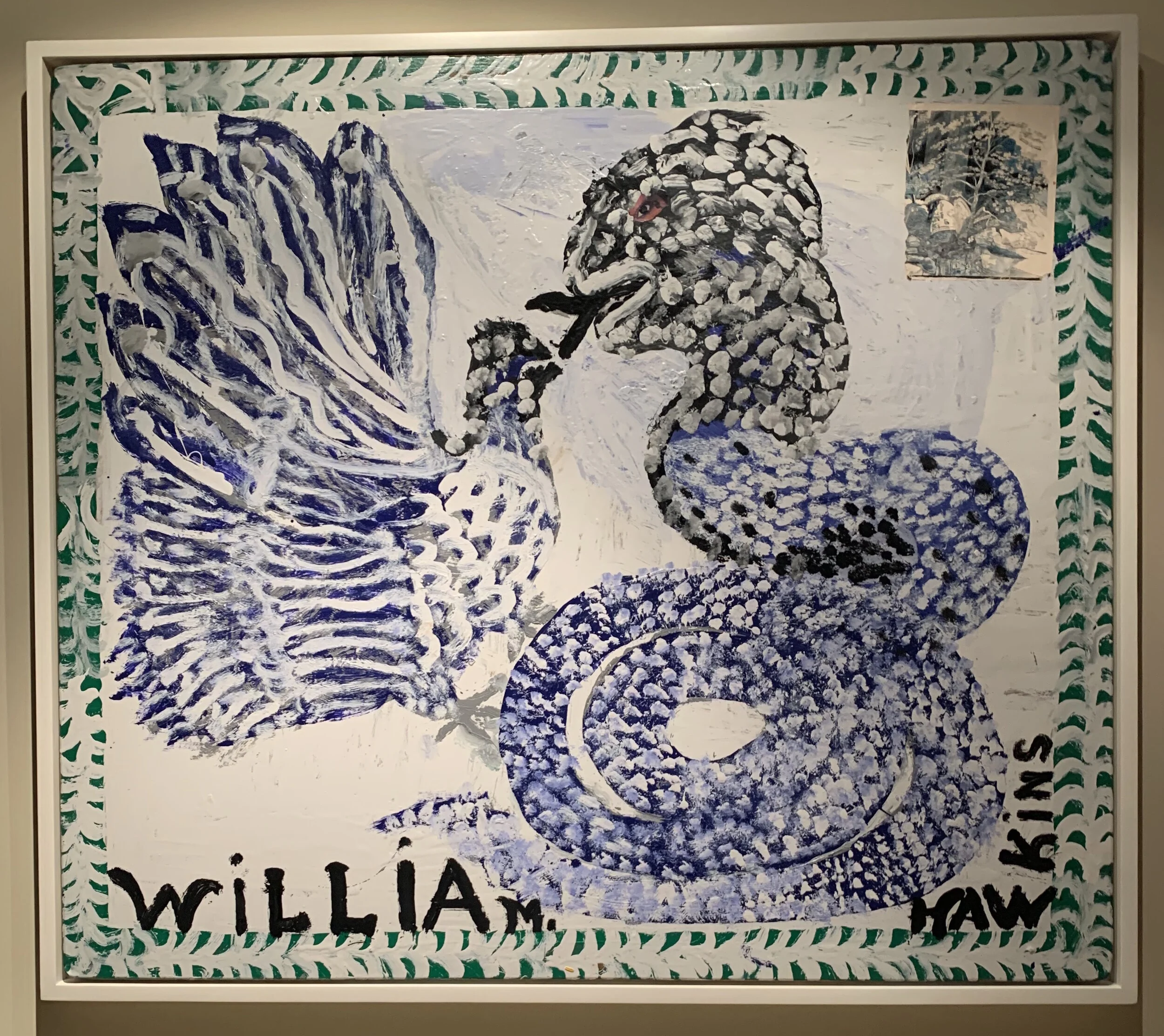

JoAnn: We did talk about this earlier though. I think the William Hawkins painting above the fireplace in our living room of a big coiled snake poised to do battle with an eagle with outspread wings, is really, really beautiful. We both love that piece. And then we also have a couple of James Castle sculptures that we love – his constructions, particularly one of a big white bird and the coat and vest Scott mentioned.

Scott: I want to just go back to one question about JoAnn and her interest in art. Since we've been married, she's become much more aware of and interested in some of the outsider art that I'd been collecting. As she said, it’s not just about the art; it’s even more about the artists and their very improbable backgrounds for becoming artists. Recently, she's become much more game, I would say, in terms of collecting, so we've started to focus together on collecting some of the best known outsider artists, whereas I used to just find works I liked and bring them home, hoping they wouldn’t be rejected. You know, we're really a team now, and it's great and a natural progression for us. So, recently we bought a Bill Traylor drawing together, and we bought three small works by Henry Darger together, and she’s become as excited about some of these artists as I am.

JoAnn: I had no idea what I was getting into being with a true collector.

Here is “Prima Verde” (or “First Green”) by Chicago Imagist Ed Paschke, taken from the Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington, our first President, that appears on the one dollar bill, a multi-layered play on words

Jennifer: Great! So they are your favorite artists, and you mentioned earlier about the 1982 show in Washington being really important at the Corcoran Gallery. Would you say there's any other exhibitions that you think have been groundbreaking for this field?

JoAnn: I think that the Outliers and American Vanguard Art exhibition at the National Gallery in D.C. two years ago was outstanding. I thought it was just terrifically put together. It really helped others understand what outsider art is and how it holds up with cutting edge American trained artists. And I liked all that art coming together in a holistic way versus just seeing an exhibition of outsider artists or just an exhibition of vanguard contemporary artists - putting everything together, I thought that was quite an important show.

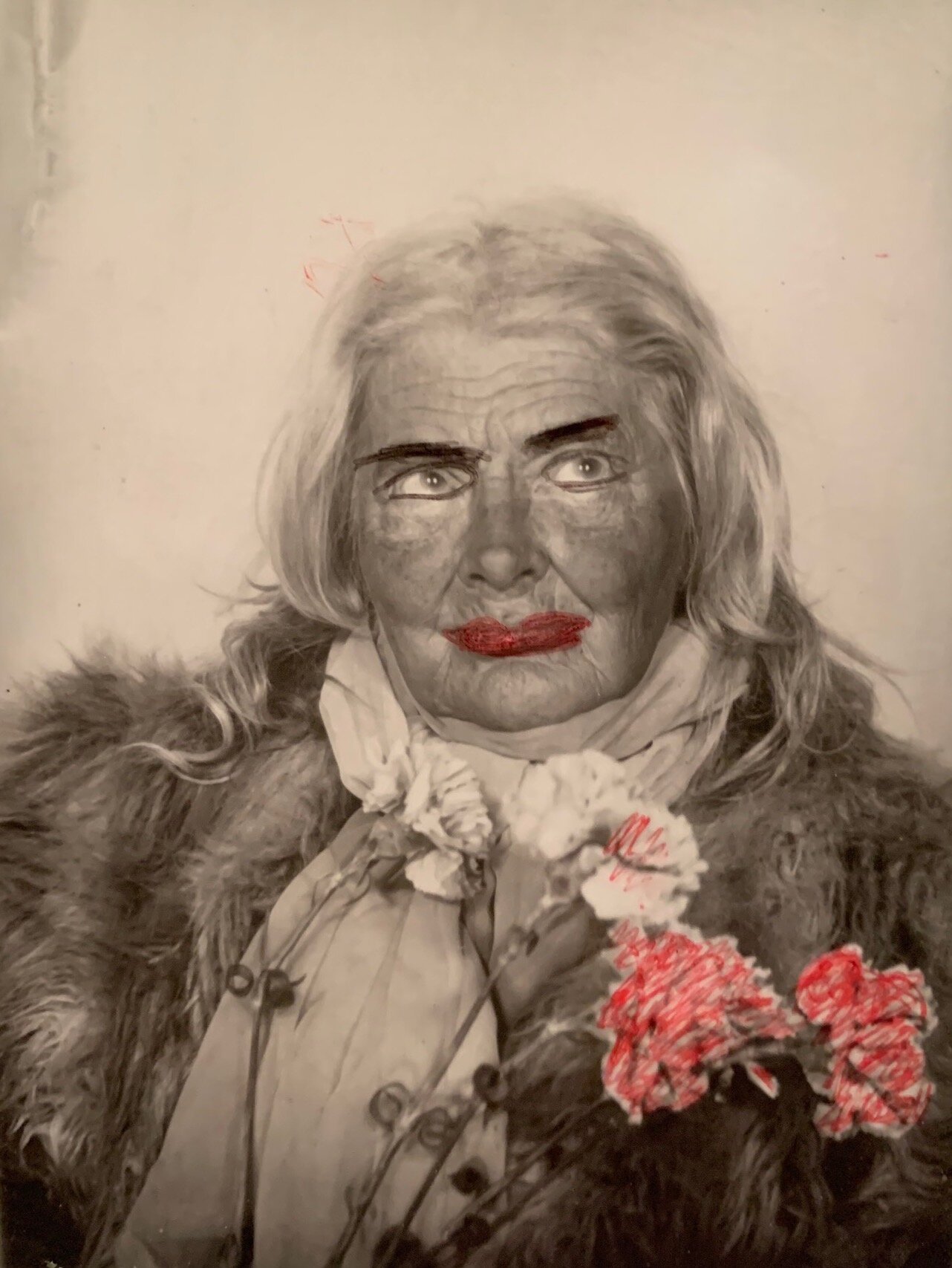

Scott: And we probably had the smallest work on loan in that show, a Lee Godie photobooth photo, which the curator hung next to a self-portrait photo by Cindy Sherman, who collects and pays homage to Lee Godie’s photobooth self-portraits. And by the way, the Godie photobooth photos are among our favorite things in our collection.

Jennifer: Well that makes sense.

Scott: It was just an outstanding show and it was really extensive… it went on and on. It was an education, even for people who were already collectors and knowledgeable about outsider art. The curator of that show, Lynne Cooke, had come to our house a long time before that, when she was putting together the first major James Castle retrospective for the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which traveled to the Art Institute and the Berkley Museum. I loaned several Castle works to that show.

JoAnn: Then there are the shows at Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, a small but very important museum here in Chicago. The exhibitions are tremendous. It’s hard to point to a single one that stands out more than the others, because they're all just so interesting and beautiful and unusual. I think they do a great job, and they have been extremely important for the development of the public’s understanding of outsider and self-taught art and artists.

Scott: Intuit, which was founded by a group of collectors of outsider art collectors in the early 90’s and later became a museum, brought many of the best outsider artists into the sunlight, and most of those artists have continued to grow in importance and become widely appreciated, not just in Chicago, but around the country and even around the world. I’m thinking of Henry Darger, James Castle, Bill Traylor, and many other early and even recent shows at Intuit. There is obviously also the American Folk Art Museum in New York, which is a fabulous organization and has some of the best outsider artworks in its permanent collection, but it's also a museum for folk art, not just outsider art – which is where it differs from Intuit. So, when you think about it, Intuit is the only museum in America devoted solely to outsider and self-taught art. There are a few small museums in Europe with a similar focus, but we have to show Intuit some love for its singular dedication to the outsider/self-taught art genre.

This is the William Hawkins painting above the fireplace in our living room, which is “Untitled” but we call it “Eagle and Snake.” Note the collaged human eye on the snake and the collaged landsacape in the upper right corner - one our favorites!

Jennifer: Definitely. So following on from that, are there any people within this field that you think have been important to pave the way for where we are today?

Scott: Yes. I think Jean Dubuffet, the famous French surrealist and abstract artist, was one of the most influential. Dubuffet actually came to Chicago in the early 50’s to present a “manifesto” at the Chicago Arts Club. It was only a few pages long. The essence of it was that authentic art is not, and cannot be, taught in universities, or in the art academies. It comes from a different more personal and immediate source. At that time, he was already fascinated with art made by artists in mental institutions, artists like Adolf Wolfli and others. He called it “Art Brut,” or “raw art” in English. And now there's a museum called the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland, which started with Dubuffet’s collection. It’s not an accident that Intuit has a show on display there right now exhibiting the works of 10 Chicago outsider artists. It’s called “Art Against the Flow,” and most of the works come from collections of Intuit members, including three works of ours. As JoAnn says, Intuit rocks!

Jennifer: Oh yes, I saw that show when it was at the Halle Saint Pierre in Paris, as it is travelling around, isn’t it?

Scott: Right. And back to Dubuffet. He came to Chicago in the 50’s to read his manifesto at the Arts Club here. I’m not sure why he chose Chicago, but I assume a lot of Chicagoans heard it and started looking at outsider and self-taught art a little differently after that. Probably the next most important show was the Corcoran show, Black Folk Art in America, which we already discussed. But I want to say something about that exhibit, because in the US right now, and in Europe, too, contemporary African American art is gaining increasing importance in terms of its collectability and rising market values. But African American outsider artists, which probably account for half or more of all well-known American outsider artists, comes from the same roots and many of the same influences as African American contemporary artists – from Africa to slavery in the South, to the Jim Crow replacement for slavery, to the Great Migration to the big cities in the North and West, etc., but they have yet to be recognized as connected in any way. I am not sure why that is, but I think that is likely to change. The art of most Black American outsider artists basically came out of their shared cultural legacy as Black American contemporary artists, which in America can usually trace itself back to slavery and the culture of the enslaved south. The big difference is that the outsider Black artists never got exposure to art schools and mainstream culture that Black contemporary artists did. In fact, “Slavery Time” is the name of a major work by Elijah Pierce, who understood exactly where his art was from and what it was about. I think the Black contemporary artists in the US, who are getting so much well-deserved currency today, really owe a debt to the African American outsider artists who mainly came before them. If and when that begins to be better understood, I am hopeful Black American outsider art works will be viewed by Black American contemporary artists, and the mainstream art world in general, with greater understanding and importance. That hasn’t happened much yet. There is a debt there that hasn’t been acknowledged, and hopefully it will be. I am thinking of outsider artists like William Traylor, Joseph Yoakum, William Hawkins, Elijah Pierce, William Edmondson, Sister Gertrude Morgan, Sam Doyle and many, many others whose work has finally started to get some recognition from the mainstream art world and become collectable, but it’s been through the sheer talent of their work, without the influential connections that many Black contemporary artists have been enjoying as of late.

Jennifer: That’s interesting. And are there any other people you want to mention?

Scott: In the outsider and self-taught genre, a limited number of galleries and private dealers have made huge differences. Among those JoAnn and I know, I'd mention Frank Maresca at Ricco Maresca Gallery in New York, Carl Hammer at the Carl Hammer Gallery in Chicago, John Ollman at Fleischer Ollman in Philadelphia, Andrew Edlin at Andrew Edlin Gallery in New Yok. These are the ones we know the most. I think Jeffrey Wolf, although not a gallerist, has had a big impact, since he’s one of the only film-makers documenting the lives of some of leading outsider artists. I don't know if many people in the public are aware of his films, but they're going to be over time.

So guys like Frank Maresca and his partner Roger Ricco focused on artists like William Hawkins, like there was no tomorrow. They helped him and gave him materials and exposure. Hawkins went on to become a fairly successful self-taught non-mainstream artist while he was alive, but two years ago, almost 35 years after his death, Hawkins had a beautifully curated four-museum touring show that was a knockout, and I predict his work will grow and grow in importance, because it is bold and playful, untamed by conformity to any artistic norms, yet usually touches on important themes or is just wacky and really appealing on its own, and he made his art in his 80’s using pretty unique techniques. You know, there's a history here that hasn't all been told. So hats off to Ricco Maresca for pulling William Hawkins more into the sunlight and to Susan Crawley who curated Hawkins’s traveling museum show. I also want to mention the great outsider art dealer, Duff Lindsey of Columbus, Ohio, who has been an ardent and very personal supporter of Elijah Pierce and William Hawkins, both from Columbus, as well as Lonnie Holley and others who he has helped climb the rungs of the ladder while they were alive as well as afterwards.

The gallerists and museums who have had the belief and courage to sponsor these relatively unknown artists have made a huge difference. They did it to make a living and pay the rent, to be sure, but they take risk and do so out of tremendous conviction and passion for the work, and that has not been very remunerative until very recently. Carl Hammer with Henry Darger, Bill Traylor, Eugene Von Brunschenheim, Lee Godie, Mr. Imagination and others; Frank Maresca with Bill Traylor, William Hawkins, Martin Ramirez, George Widener, and many, many others. John Ollman with James Castle, Elijah Pierce, and many others. I don’t know all their stories. I believe the Godmother of them all, the one who first tied together the aesthetics of outsider artists and Chicago Imagists, was Phyllis Kind, who had a Chicago-New York Gallery that represented Chicago Imagists and outsider artists very early in the game. One of her proteges, a private dealer named Karen Lennox, who lives in Chicago and continues to sell really great Chicago Imagist and outsider art works from her apartment, knows the whereabouts of much of the art that traveled through the Phyllis Kind Gallery, Carl Hammer Gallery, and Fleischer Ollman Gallery early on. She has been instrumental in helping us and others collect great early works by the Chicago Imagists and outsider artists from Chicago and elsewhere. Without these people and others like them, there would be much less awareness, access and appreciation for these artists and their works, and that would be a shame. So they are unsung heroes in my book.

Works by Mr. Imagination (Gregory Warnock) of Chicago

Jennifer: Given all that, where would you say you buy most of your work from, is it from the gallerists and the art dealers, or do you buy from auctions or from art fairs or directly from the artists?

Scott: All of the above. Wherever we find them, especially the outsider artists. We have bought quite a bit of work from galleries. We go to the Outsider Art Fair in New York every year where dozens and dozens of galleries from around the world show their works. But we’ve bought works at art auctions and infrequently from other collectors. Christies in New York has an Outsider Art Auction in each January during the same week as the Outsider Art Fair, and that’s been a major boost to the genre, because the more selling outlets the better. It’s like the stock market, the more liquidity, the more safe and more attractive the market is, and a name like Christies endorsing an art genre with recurring annual auctions adds a lot of credibility and even permanence. I’m told a lot of the Intuit founders used to buy directly from the artists. They would get in their vans, travel to remote places, befriend the artists and their local dealers, and purchase their works. Some accumulated a lot of work that way and helped to raise the profile of now famous outsider artists like Howard Finster. They forged relationships with artists, in some cases over decades, that were special, like they became part of the family. It was symbiotic. The artists could sell their works for more money than they could get locally, and the collectors could buy the works for less money than they’d have to pay to galleries in their home markets, plus they could choose from a much larger selection of works. But there’s no real liquidity in that, and those old bargain basement opportunities and special relationships with artists are mostly over now. So the galleries, dealers, auction houses and museums will be where it’s at.

JoAnn: I’ll just add to that, I think the first time that I went to an exhibition of outsider art was of course with Scott at Intuit and it was an exhibition about Mr. Imagination. It was a whole collection of his art and it was outstanding. There were so many pieces, and at that particular exhibition I started talking with a woman I'd never met before, Sherry Siegel. She told me about her friendship with Mr. Imagination that lasted many years, and she even got a little teary, because he had passed away not long before the exhibition. She really cared about him. She had bought so much of his work just to keep him going on – so that was kind of her contribution to his life and business, and she would pay him, you know, more than he asked for, in many cases. So as I'm recalling the conversation that I had with Sherry, it was very moving, and all of a sudden, I began to get it - like what it is about these artists that draws people in. I'm sure, Jennifer, you must have that same kind of feeling, too, as you work with artists with disabilities. Mr. Imagination had some real challenges in his life, and to have someone like Sherry - and others, as she wasn't the only one who cared deeply about him and looked after him - this enabled him to continue to make his art and ultimately helped make his life better. So anyway, that was the first time that I really began to get what it was all about. Owning these works can bring a deeply personal satisfaction that I wouldn’t be available from more traditional artists.

Scott: Yeah, so that's why it’s becomes almost like, not an obsession, but it's like an exploration that keeps rewarding the explorer. With contemporary artists you don't get to do that, because they've already been explored and exposed and sponsored by the infrastructure that supports them, the galleries, the private dealers, the arts publications, the museums, etc., but many outsider artists haven’t enjoyed that during their lifetime.

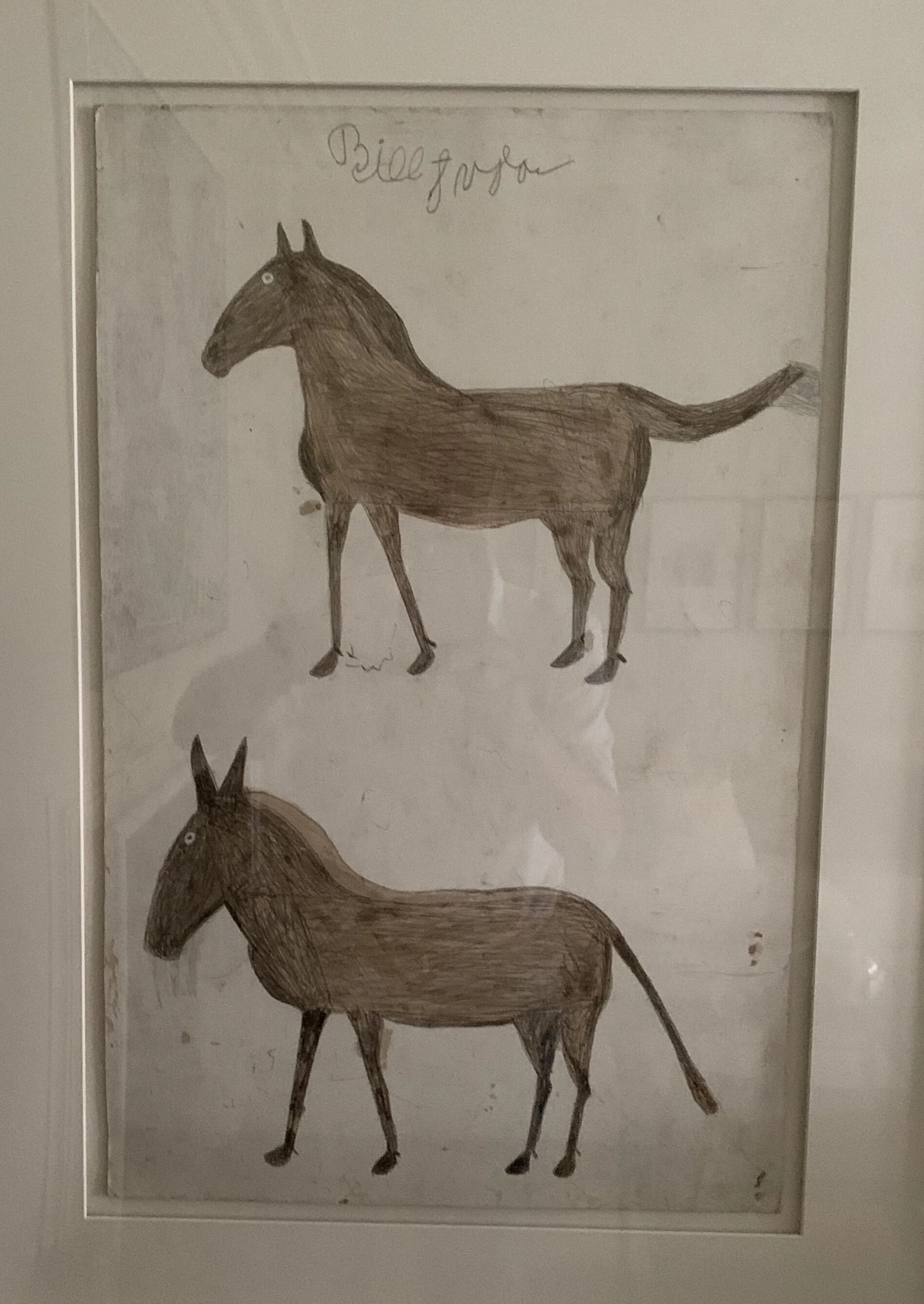

“Untitled” (Two Horses) by Bill Traylor. Previously owned by Robert Bishop from the American Folk Art Museum

Jennifer: So let’s look at the term outsider art. I'm always interested to hear what other people think. So how do you see the term outsider art? Do you like the term? Do you hate the term? Would you rather it be called something else?

JoAnn: I like the term, and I like it because it's already out there and people intuitively understand what it is. So to spend a lot of time debating something that already has meaning on a broad level is, to me, just a waste of time. Whether there could have been something better, you know maybe there could have been, but it's kind of too late. The ship has sailed on that, and that's my view of it, so I think it's fine.

Scott: We agree on that, and I think that there's already been a ton of thinking on it, and no one has come up with a better name for it. It could seem offensive to artists who don’t want to be labeled “outsider” artists, especially if they are trying to be considered mainstream, and I get that. But I also see “outsider” as a positive term. I think from the point of view of what's happening in the art world today, which is to try to make outsider art part of the mainstream, I kind of don't want that to happen, because the big museums and the major galleries will be taking it over, and showing it as if it's just another thing on the wall. I think that it would be great if outsider art can maintain a kind of separateness and independence, and a unique reason for being, while also being explored, exhibited, and valued similarly to mainstream art, but as a genre of its own, an identity of its own. Continuing to use the name “outsider art” helps in that regard.

JoAnn: I’ll add, it's not that I love the term outsider art, because I think it falls short in many ways. All art is hard to define, right? It's hard to categorize artists in any particular period, because art just can't be completely categorized in a certain way. So I think outsider art has a sort of a mystique to it. It's distinct and different, and the word “outsider” kind of makes people say, well what in the world is that? So that's kind of a good aspect of it. I think that categorizing all the artists that are in that category in the same way, however, is not the point or the right thing to do. It is just so hard to define any artist – they are never going to all fit into little boxes, so there’s never going to be a perfect definition.

Jennifer: Scott, you were saying you don't want to see it kind of integrated into these big institutions. Lets say MOMA in New York has a Judith Scott in a room full of contemporary art. I saw this in January 2020, and I thought that was great because it wasn't seeing her as this different person, it was saying, look at this incredible art alongside all these other incredible works.

Scott: I don't disagree with that at all. Many other mainstream museums are doing that now, like the Whitney, the Met, The Art Institute, the Tate – mostly just an outsider work here and a work there. The Milwaukee Art Museum has a small space dedicated to outsider and folk art on permanent display, as a genre of sorts, which was pretty unusual when it first came together a few decades ago. I’m sure others do as well like the High Museum in Atlanta, and others. While I do think nowadays it is very hard to label an artist an outsider artist, given social media and all the political correctness and culture wars surrounding us now, I do think it's helpful to identify a category of artists who live and work outside the mainstream, who do not have a great support system and who nevertheless produce great works. And if they are accepted into these big galleries and museums, that’s wonderful, but even if they don't make it in, it's great to know there's this whole unique genre out there into which they fall. I want their work to be shown along famous artists, because they are also entitled to become famous artists, but I don’t want to see them lose their uniqueness and identity. They are just people like the trained artists are just people. What’s different is their non-mainstream backgrounds and their improbable paths to success as artists. That difference seems worth recognizing and saluting. Like, when we went to the Art Institute of Chicago a few years ago and saw a limestone sculpture by William Edmonson on a pedestal in a room with paintings by famous post-impressionists – that surprised us, because we were not used to seeing that. But it also made us feel great, because we have seen the pictures of Edmondson taken by Edward Weston showing his incredibly hard-scrapple living conditions, and we know that there must have been something very unusual, very special about him to have lived in such poverty and still create such great works of art out of stone that are now sometimes compared to Brancusi or Arp or Picasso.

JoAnn: I would also say that when we read the New York Times arts section these days, we frequently see new outsider artists written up by the paper’s main art critics, and that's pretty exciting. I think Scott makes a good point, that it’s getting harder to find outsider artists that remain undiscovered during most or all of their lives like James Castle. And social media is making it harder and harder for artists to live outside the mainstream culture.

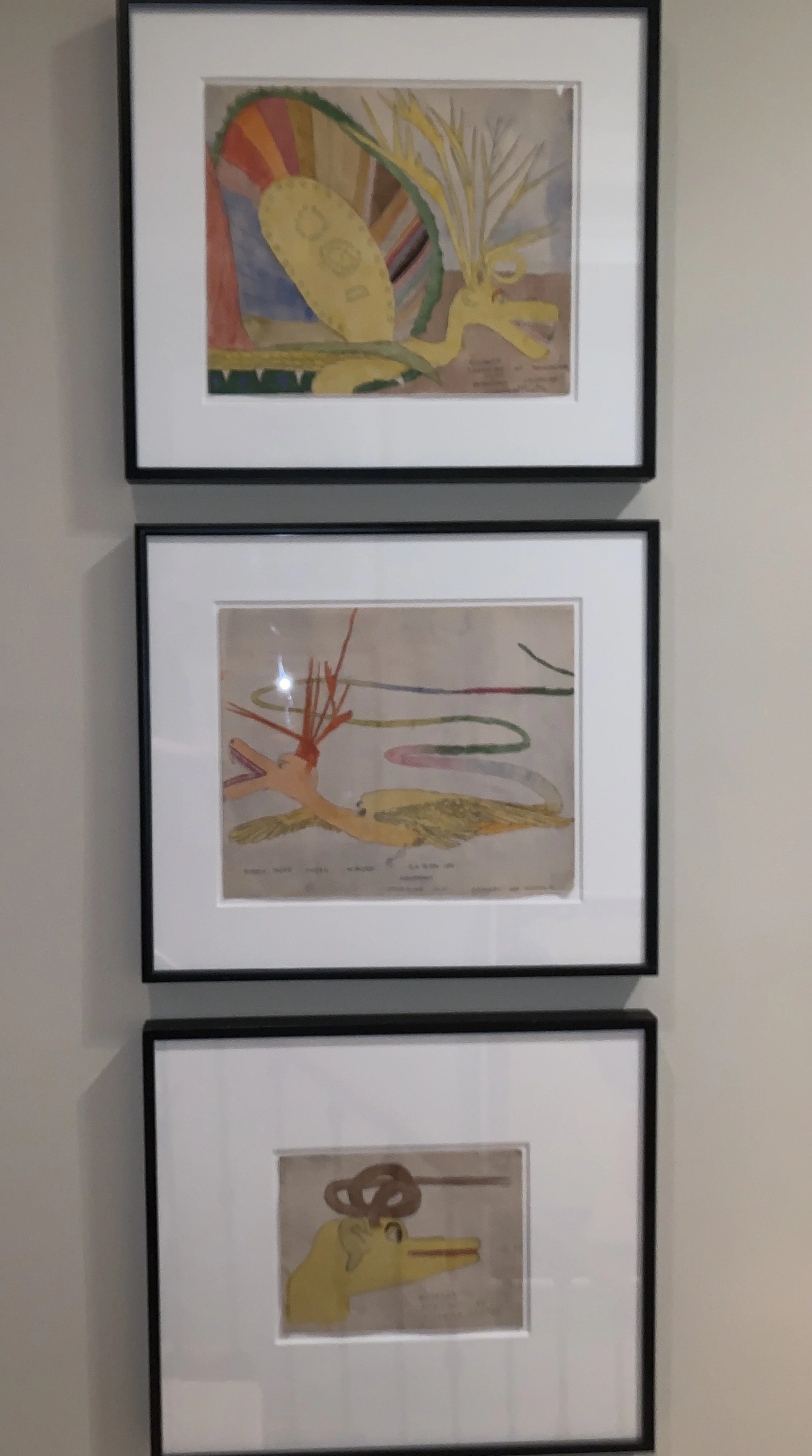

Three watercolor and pencil drawings by Henry Darger

Jennifer: Scott, you're the vice president of the board of Intuit. So when did you become a board member and why are you so interested in that museum?

Scott: Well, that's good question. I was a founder of Intuit back in 1991. Carl Hammer, a friend of mine, asked me to donate $250 to this new organization called “Intuit,” and I said okay and wrote a check, which made me founder of Intuit without even knowing what Intuit was about. That was it. Intuit wasn't intended to be a museum then, and I wasn’t intending to be actively involved. Intuit started out as just a collective of collectors who wanted to share their interest and their finds in outsider art. At that point, I was not a serious collector, and I actually forgot I was a founder until about five or six years ago, when I was approached by two of Intuit’s leading board members, Bob Roth and Cleo Wilson. They knew we had been building an art collection with some good outsider works, and they asked me if I would go on the board. I took a look at the physical space and the financial statements and said the only way I would consider doing that was if they agreed to create a high-quality, modern physical space and raise enough money to convert Intuit into a modern museum, including the technology that is available today. They said okay, and then rewarded me by asking me to lead a major capital campaign, for which I had no prior experience and for which they had very few financial supporters. Deb Kerr had just become the Executive Director of the museum. She has tremendously positive energy, and she thoroughly embraced the idea, as did a lot of other people on the board. But you know, it’s been daunting. Intuit was originally a collective that had become a museum with very modest investment, mainly from a few board members, and it lacked a sympathetic cause like curing a horrible disease, serving depressed communities, fostering education, etc. Many of the early Intuit exhibits were amazing and brought notoriety among the collectors in Chicago and around the country. But Intuit had no money in the bank and had never had a capital campaign. To think about raising $4 million or $5 million was, in hindsight, a preposterous idea. But we started the campaign a few years ago, got it off to a good start with tremendous support from current and past board members, and we managed to buy the floor above us to double our space going forward and we added professionals to the staff. But then we found we still didn't have quite enough money to start construction when the pandemic came along and we put the capital campaign on hold. Now, I hope and think we will get it done, because we've got a truly beautiful plan for the museum, the outsider genre has continued to grow in stature, even during the pandemic, Deb and her team have developed amazing educational and community outreach programs that make us more relevant in the charitable giving world, and the appetite and need for a museum like the new Intuit have become greater than ever. We are missing only a few anchor donors, I think, to get the construction launched, and hopefully we will find them.

I think one of the distinguishing things about the outsider art world, which may be hard for people to appreciate, is there is no strong voice for these artists who have created amazing artwork against all odds – “against the flow,” if you will. Certainly not like mainstream artists who are supported by major galleries, museums, art periodicals, and wealthy collectors with a vested interest in their artists’ success. There are galleries that support outsider art, as you know yourself, because you own one. But that’s not where the deep pockets are nor where the money flows, at least not quite yet.

So Intuit started out as more or less a collective of collectors. It's probably not well known, but Intuit had the first exhibition of James Castle’s work outside of Boise, Idaho. Probably nobody outside of Idaho was even aware of James Castle then. Intuit, together with Fleisher Ollman and Karen Lennox, really helped put Castle on the map. But when Henry Darger died, a quintessential Chicago outsider artist, Intuit, which was among the first to show his work but had no benefactor to help acquire any Darger works, so Intuit got none. Fortunately, Intuit did get contributed all the contents of Darger’s efficiency apartment, where he created all of his art and wrote his books, and with that stuff, Intuit recreated a replica of the “Henry Darger Room” inside its walls. People now come from around the world to visit the “Henry Darger Room,” because Darger has become the most iconic outsider artist and cult figure of the genre, and with the Henry Darger Room, Intuit continues to play a central role in that. Visitors to Intuit can see what his living arrangement was, the source materials and implements he used, and begin to appreciate his phenomenal artistic achievements under almost unbearably cramped, isolated and depressing conditions. In the new Intuit, we're planning to move that room and its contents, which is now buried in a dark corner in the back of Intuit first floor, to the very front of the building, sink it down below street level onto the floor below, and leave it open from the top, so visitors can see into it from above and go down and look into it through a glass wall, even enter it with permission. And we're going to have a two-story wall above it describing key elements of Henry Darger’s life and art for the world to understand better how unique this artist truly is and how far outside the mainstream he lived. A true monument to an otherwise inscrutable artist!

Jennifer: That's amazing. So what's next for you both. I'm guessing you still want to add works to your collection? And would you ever do a show that's just works from your collection?

JoAnn: Parts of our collection get loaned out to shows, like nine Lee Godie’s photobooth photos recently left for a show in New York in January at the American Folk Art Museum. It’ll be a show about outsider artist photographers, and I think Godie will be the only female artist in the show. My challenge then becomes the fact that Scott will then see a blank space on the wall where those works used to hang, and he’ll want to fill it as if those works were never coming back!

Scott: We haven’t really thought about a show of just our collection, because there are far more important outsider art collections than ours that would make excellent exhibits. Intuit has one up now of works from the collection of Victor Keen, a Philadelphia lawyer and long-time outsider art collector, which has been an eye-opener for Chicago collectors. Ours is also very much a personal collection, as you can tell from our original comments about blending works by outsider artists with works by the Chicago Imagists and other contemporary artists. But we have had many visitors including a few groups in from Chicago and other parts of the country to view our collection, and that’s been fun for us, and for them. The energy from the art in our home is pretty amazing, and people are drawn to it.

This is the Lee Godie photobooth photo included in “Outliers and American Vanguard Art” exhibition at the National Gallery of Art

Jennifer: I think it’s quite interesting when I talk to people and they say they have people round to their house and their friends that might not know about outsider art, and some of their friends find the artwork very strange – how do your friends react?

Scott: Well they almost all love it, but then we don't have a lot of really strange pieces. I think we both look at the work from standpoint of beauty and the positive energy we get by living around it, and that’s what we collect for. That goes for mainstream art as well as outsider art. If it’s not going to make us feel good and enhance the beauty and interest of our home, we do not want to live with it. I think that’s the common denominator.

JoAnn: Our collection is much more curated from the standpoint of our aesthetic sense of what is beautiful to us. For example, one of my favorite parts of the collection is a whole grouping of a dozen or so Mark Catesby botanical prints done in the mid-1700s. Catesby was English and actually a self-taught artist. But he was from mainstream society and not considered in the outsider art category. I happen to love his documentation of the flora and fauna of this new world, which is what he came over from England to do. His works are just charming and whimsical but usually a little odd, and they are all beautiful and incredibly well done, especially for someone who taught himself how to make art. Scott had never heard of him, and when he realized Catesby was a self-taught artist, that made Scott super excited about him, and Catesby has become an important part of our collection. I never get tired of looking at them in our bedroom. They are so peaceful, strange and very beautiful.

Jennifer: So my final question is, is there anything else that you'd like to add?

JoAnn: I would say the gallerists and private dealers who deal in outsider art - they do it with a passion. It's a personal interest and excitement, and as a result they have been some of our best teachers.

Scott: They are the best source for the art, even though they may be more expensive than other sources. If you get to know them and trust them, they can be of tremendous value, because they want to share their expertise and knowledge, they want to help any collector make better decisions. Unfortunately, a lot of the gallerists and dealers who have helped us and so many other collectors discover and appreciate outsider art and create collections with some great works, are now reaching an age where they're not going to be able to do it for many more years, and there don’t seem to be many replacements coming up behind them. In New York, Andrew Edlin, who you probably know, and Scott Ogden from Shrine, are two great exceptions, and Cara Zimmerman of Christies, who has been responsible for their Outsider Art Auction since its beginning, is another major young force in the outsider art world – they’ve all got the ‘zeal’ and the eye it takes.

JoAnn: I'll just add one more thing. Another person that made a huge difference for me is Karen Lennox, who Scott mentioned. When I first met Scott, he would often go see Karen, who deals art from her apartment, and he’d come back a few hours later with outsider or Chicago Imagists works, since she deals in both. So I was like, who is this Karen person? Then I went with Scott to meet Karen one day, and she taught me so much about each piece of art that she had there. I learned so much about the artists, about their stories, and the histories of how these artists had been collected. So I began to love going to see Karen, too. She wasn’t always pushing to make sales, but she was just excited to share stories and artworks, because she truly loves and knows all that. She really helped with my appreciation and understanding of this genre of art.