SAMUEL RIERA AND DERBIS CAMPOS - MEET THE COLLECTOR SERIES PART SIXTY FIVE

It has been a while, and then a translation from Spanish to English occured, but I bring you Meet the Collector Series part sixty five, featuring the two people who formed the Riera Studio and the Art Brut Project Cuba in Havana. It’s been fascinating to hear their studio and the change in Cuba over the years, and still how this work isn’t really respected within galleries and museums there. If you’re heading to Documenta 15 in Germany during August 2022, you will catch a large display from their collection! Grab a drink, find a comfy seat and read on.

Samuel Riera and Derbis Campos

1. Can you tell us a little about your background?

Samuel Riera (SR): My name is Samuel Riera. I am a visual artist with more than 25 years of arts experience. I graduated in Graphic Arts at the National Academy of Fine Arts ‘San Alejandro’ and at the Higher Institute of Art of Havana (ISA). For 16 years I was also a Professor at the National Academy of Fine Arts ‘San Alejandro’. Derbis Campos holds a degree in Biochemistry and a Master of Science degree from the University of Havana. For more than 15 years he was a researcher in Medical Genetics. His interest to the arts was through photography.

2. When did your interest in the field of outsider/folk/self-taught art begin?

Derbis Campos (DC): First a brief reference to the particular characteristics of our country, with a political system that centrally controls the different aspects of society, including art, drawing up guidelines and methodologies that regulate the different stages of artistic creation – from its conception to its promotion, both nationally and internationally. Until the late 1990s, these processes were extremely rigid and plagued by misconceptions and imported notions that had nothing to do with our socio-cultural background, motivated by the close link that for decades kept us as a satellite state of the Soviet Union. Thus, artistic expressions within the visual arts that gave rise to the slightest doubt about their ideological content, or that of their creators, were completely crushed and doomed to fail. On the other hand, the process of ‘culturalisation’ of Cuban society undertaken from the 1960s, with the establishment of the communist character of the Cuban Revolution, promoted the creation and establishment of governmental cultural institutions. A tiered system was created, ranging from communities to a national scope. They had as one of their objectives the identification of the different creative potentials from different communities. This centralized government system also covered all the galleries and exhibition spaces in the country. In a historic meeting with the leading Cuban intellectuals of the time, the historical leader of the Cuban Revolution, Fidel Castro expressed: "Within the Revolution everything, against the Revolution nothing..." (1). That phrase would become the manifesto of the country's cultural policy until today. This process indisputably had disastrous effects on creating institutionalized artists as they looked at things with a purely academic aesthetic model, ignoring authentic creative processes and popular art expressions.

From the 1980s, creative processes began to manifest themselves within the academies that somehow critically confronted the art systems in place, and the social and political reality of the country. They sought to transform and update cultural thought that had become weighed down by decades of old conceptions. Then, in the 1990s, with the fall of the iron curtain imposed by relations with the Soviet Union, and the socialist countries of Eastern Europe, a deep economic crisis was established that forced the country to make changes in pursuit of greater openness to the international market. This also influenced art, by creating new strata of artists and conditioning new aesthetics of creation and appreciation linked to specific markets. It is here when initiatives begin from independent positions uprooted from the institutional system to also visualise those creative processes and potentials, called alternatives, that were outside the mainstream.

SR: This phenomenon for me was very motivating. As a professionally trained artist and Professor at an art academy, the training received inclined me to think that all artistic expression was always developed from a link with art institutions. However, at the same time, I saw the development of creativity outside this area, with another level of freedom and expression. I always had the concern of trying to see art from different angles, without framing it in an established trend or norm. And that's a wonderful approach.

From 2008 to 2010 I was in Venezuela, working in a multidisciplinary government program for social groups with a high rate of drug addiction, and without protection. My purpose was to use artistic methodologies as evaluation, diagnostic, therapeutic and socio-productive insertion tools for these people. This work awakened in me the approach, as an artist, to social issues by linking directly with marginalised groups, and being able to recognise the therapeutic value of art. Elements that, even without being fully aware at that time, would serve as a basis for me to understand, accept and defend forms of artistic and aesthetic creation, with which I would link myself in the future.

From the beginning of the work at RIERA STUDIO, I set out to accommodate proposals from creators regardless of whether or not they had professional artistic training, only motivated by the strength and transgressive content of their works. Many of them were creators marginalised by the standards and aesthetics accepted by government galleries and exhibition spaces. We weren't talking about Art Brut and Outsider Art at the time. These were terms virtually unknown in our context, even at the level of academies and circles of art historians, curators, critics and specialists. We hardly found any historical references, only the work of Samuel Feijoó (2) with the “Grupo Signos” and his friendship with Jean Dubuffet in the 1970s – 1980s. There were also no records of artistic activities in mental health institutions.

In 2013 I met, on his visit to Cuba, an Art Brut collector. The absence of references to Art Brut and Outsider Art made in our country, of cataloguing its creators and their works, of initiatives aimed at its promotion and dissemination and the purpose of forming a collection of this totally Cuban art, led me from that moment to investigate it, and begin it as a professional and personal project.

As a first strategy I decided, for about two years, to depart almost completely from the dynamics of contemporary art in our country. If I wanted to understand the world of Art Brut and Outsider Art I had to stop going to exhibitions and events of contemporary art and stop visiting art institutions. I had to go through a process of visual purging, not because contemporary art was flawed, but I had to re-educate my visual patterns to be able to understand an art with a completely different aesthetic. To be able to assimilate the complex social field of its creators, and to understand the responsibilities acquired by those who promote their works.

Staying isolated, without being isolated, accentuated my observation about other realities little seen within our social-artistic context, and I understood different social phenomena and modes discriminately categorised as sub-cultural, marginalised and undervalued by a prevailing artistic elite and the institutionalised system of art and culture in our country.

View of an exhibition room at Riera Studio with pieces from Art Brut Project Cuba Collection. Photo credits: Samuel Riera and Derbis Campos. Riera Studio

3. When did you create RIERA STUDIO in Cuba, and did your collecting start sooner or later? Can you tell us about the study and its purpose? It seems like it's not really a study that people go into creating, like other studios in the world, is that correct?

DC: In Cuba, the entire system of commercial galleries belongs to the state, so its programming, gallery artists and dissemination interests respond to the hegemonic and strict lines of the governmental cultural system. From the 1990s (3) and with greater force from the XII Havana Biennial in 2012, the opening of some private spaces occurred, that independently made visible artistic processes separate to the exhibitions curated from state institutions and galleries.

SR: It is in this context that I decided to transform my own house into an exhibition space to show not only my work, but also that of other artists who were developing their work away from the mainstream art in the city. We founded RIERA STUDIO in 2012 with the curatorial project – Pura Mancha – in which young professional and self-didactic artists were included, and whose axis lay in the questioning of the value of art and officialdom.

We created RIERA STUDIO, not only as an exhibition space, but also as a space that fosters study, reflection and cultural dialogue around different dynamics of art created outside the established norms, its interrelation with society and the different processes and social contexts of its creators. Our interest would focus on the promotion of art forms made by vulnerable social groups and other creators who develop their work outside official art institutions or other platforms, in response to a strong intrinsic motivation and as a reflection of unique mental states, very individual idiosyncrasies and extravagant fantasy worlds.

In 2013 we inaugurated the first exhibition of an Art Brut artist – Simple Art – with works by Carlos Javier García Huergos. This is how Art Brut Project Cuba emerged as a platform from RIERA STUDIO, that would go on to house all those creators that we could identify after big investigations throughout the country. A project that would provide protection to their works and permanent advice to both family members and specialists interested in the subject. We wanted to offer both national and international recognition to each of them and provide sufficient conditions and means for the development of their works, to those creators who needed it.

DC: From its conception of studio-gallery nestled within our own house, RIERA STUDIO constitutes an atypical space in which art is resized from its curatorial exhibition, to an environment in which work and life are shared. We have three exhibition rooms: one of them is generally dedicated to the exhibition of the works housed in the Art Brut Project Cuba Collection, which is renewed at different times of the year, and two rooms dedicated to temporary curatorial projects and experimental projects. In addition, the studio has a work room where a small number of artists from Art Brut Project Cuba create at different times, in an alternative way, then an office-warehouse and another work room for our own work.

Art Brut Project Cuba is a project that works completely independently, that is, we do not receive funding from any cultural institution in our country or a systematic fund from other foreign public or private institutions. The different actions we carry out are largely based on our own personal funds, as well as the support of numerous friends and collaborators, obtaining funds from calls and specific scholarships and collaborations and joint projects with other international institutions.

It is important to mention that in our country there are no art studios for people with intellectual and/ or mental health disabilities. Even actions that use the classic approaches to art-therapy as a tool to support treatment and recovery are practically non-existent in different mental health institutions. Different factors contribute to this: the systematic lack of art materials, the lack of an art facilitators with availability, and enough sensitivity to work in these health institutions. There is also the ignorance or undervaluation of arts therapeutic value. Due to there being no art studio spaces for people with intellectual and/ or mental health disabilities in Cuba, we find people with these characteristi that have had no art tuition and their creativity is raw and original.

SR: At the beginning, we questioned the term workshop a lot to refer to the space we offer in our studio for a group of artists from Art Brut Project Cuba because, frequently, there is the criteria that when you say workshop or atelier you are talking about a space to build, which carries instruction and methodology. That is why we always warn people that our job is not to educate to obtain a specific aesthetic result. All the artists in the project, including those who attend our studio, already had their own creative process and had been developing their artwork before they came to us. One of our main aims is to maintain those creative processes that the artists discovered for themselves by offering them the confidence and support, so that they can continue and grow. All of them continue to create in their homes and environments, even the artists who attend the studio on certain days because their attendance is not daily. For those who decide to come here, the studio becomes a space for socialisation, and exchange of experiences and support among the relatives who accompany them.

Currently, most of the artists of Art Brut Project Cuba create only from their homes and environments. It is important to mention that our studio supports artists from all over the country, not only from Havana, where we reside. With all of them we maintain close communication, visit them, follow up and support their creative processes. This allows us to establish a good relationship, as well as provide family members and / or cohabitants with comprehensive and acceptance tools will help to change the perspective that often still exists with respect to creators with these characteristics.

Each artist works alone within his own home and is completely responsible for the whole process, from the initial motivation to the development of the art. Part of our support also consists of offering them the materials they need to carry out their works but taking care that the material provided does not modify their work processes or create a dependence on the existence or not of it. We work with each of them on an individual basis and responding to the characteristics of each creator, both at the level of their creative process and their psychopathological characteristics. We assume this work continuously for as long as the artist and their family wish, always providing the tools so that even in our absence, their relatives – if it is the case that the artist is under their care – can continue to help them.

Art Brut Project Cuba started for us as an investigation, not with the intention of creating a collection, that was never the purpose. The research opened the doors to an existing artistic flow, invisible until now, and to the need to bring together all this undervalued work – first within the immediate context of the creators themselves and then of the Cuban cultural institutions. This research spread to different regions of the country and began to unravel historical profiles and establish direct or indirect connections between Art Brut, Outsider Art, Folk Art, Self-taught Art, Peripheral Art, Marginal/Marginalised Art – and even from socio-political aspects.

Thus began to emerge the Art Brut Project Cuba Collection that would guarantee the cataloging, preservation and visualisation of selected works from each identified artist. Our collection is the only one of its kind in the country, and the largest of Cuban creators internationally. More than 8,000 catalogued pieces comprising drawings, paintings, objects, sculptures; and another significant group of works yet to be registered. A collection that increases every week by adding new artists and new works from existing ones.

View of an exhibitions rooms with works by Damian Valdès Dilla (left room) and Carlos Javier GarcÌa Huergo (right room). Photo credits: Samuel Riera and Derbis Campos. Riera Studio

4. Why are you so specific on just having Cuban creators, and have you made any exceptions?

SR: The Art Brut and Outsider Art that are created in Cuba are made in a unique context, given the geographical, historical, political, and social characteristics of our country. So far, we have no historical records of creations made before 1959, so we usually talk about the context of Art Brut and Outsider Art within the communist system imposed on the island from the 1960s. Also, the massification of services such as Internet access and the use of social networks has occurred relatively in recent years and due to its high costs, it remains inaccessible to a significant percentage of the population – usually older adults, families with limited incomes, dysfunctional families, and individuals with disabilities. These factors create a limited cultural influence for self-taught individuals.

In this context, the main purpose of the Art Brut Project Cuba Collection is to preserve the results of genuine and unique creative processes within the Cuban cultural heritage. We understand that it is essential to preserve the integrity of the work of each of the artists we consider as creators of Art Brut and Outsider Art. Valuing what each of these creators had already been doing in a hidden way, has an extraordinary meaning. Most of them are not aware of the artistic value of their creations – some even destroy them over time – so deciding to incorporate them into this collection acquires even greater importance in the formation of a historical record of the work of each one. The collection comes to detach itself from aesthetic considerations, themes or other subjective elements to become the main record of Art Brut and Outsider Art made in Cuba. Our limited financial resources will continue to maintain that purpose, even though of course we admire all Art Brut and Outsider Art internationally.

5. How do you find the artists who are part of your studio and collection?

DC: We find artists through various forms, but undoubtedly two of the most important elements are the creation of multidisciplinary interconnection networks and an intense work of promotion and dissemination of our work and our collection. These creators are not found in cultural centres, as they generally live outside the existence of this cultural system. In some cases, relatives may have tried to do something with their work, but they have been rejected and undervalued by the system itself.

In the beginning, we established working contacts with clinical specialists, psychiatrists, and psychologists, who referred us to patients who at some point evidenced creative work. This continues to be a way for us to approach to these creators. We have also established contacts with specialists from mental health centres, social projects that include people with intellectual and/or mental disabilities, and some institutions of elementary artistic education. To the extent that our actions and work objectives have been disseminated in a national context based on our promotional work across different media, it has been possible to identify new creative potentials, both in Havana – the city where we live – and also in different provinces throughout the country. We generally receive this referential information from members of communities who have noticed a neighbour who is often drawing in the streets, or from a family member that say another family member often paints or scribbles.

SR: As an example, the first artist we met was a neighbour in my community: Carlos Javier García Huergo. I had known him since I was a child, and I always witnessed the harassment he suffered due to his psychotic condition. However, it is not until I decide to open the studio that one day I see one of his works – the ones he usually does on cartons or boxes that he finds. That's when I found out more about his work and his creative process that he had been carrying out for a long time, much of which had been discarded.

Sometimes, the creators of Art Brut and Outsider Art themselves behave as agents, and have led us to meet other artists, either because they share friendships or because they participate in the same circles of interests. This has been the case, for example, of esoteric study circles, or those interested in UFOs and alien civilisations, and of the Muslim religion.

DC: Once the person with creative potential has been identified, we propose to know them personally, preferably in their own home and this is how we verify their creative processes and seek to inquire about their life history. With all that information, we decide on its inclusion in Art Brut Project Cuba. Elements that we always keep in mind when we meet a new artist are: acceptance, humility and trust. Establishing a bond of trust is extremely important to be able to approach with complete sincerity their creative processes and that they can share their work with us and then if they decide to become part of Art Brut Project Cuba.

View of an exhibition room at Riera Studio with pieces from Art Brut Project Cuba Collection. Photo credits: Samuel Riera and Derbis Campos. Riera Studio

6. Do you want to share anything else about the collection?

SR: The collection also includes works with a historical heritage value made by deceased Art Brut and Outsider Art creators - both artists who were part of Art Brut Project Cuba, as well as others that we did not have the possibility to meet. Special attention in this sense is the archive that we have been forming with works made by Samuel Feijoó, and by the artists he brought together under the name of "Grupo Signos". These self-taught artists constitute the first approach or historical reference to Art Brut in our country, with works between the years 1970 – 1990. Also included in this archive are works by other authors and dedicated to Samuel Feijoo, including works by Jean Dubuffet. We have also included in the collection works of patients from mental health institutions – who although we have not been able to have a relationship with them – we have been donated some of their works by psychiatrists and psychologists with whom we have established work contacts.

7. Does each of you have a favourite artist or work in your collection? And why?

SR: We don't really define favouritism within the different artists we work with, neither in relation to their creative processes, nor in relation to the result of them. Of course, each artist is completely different both from the point of view of the development of their creativity and the result, but we try not to be biased by an aesthetic subjectivity. For us, delving into the complexity and uniqueness of the creative processes of each of these artists is a wonderful sensory experience. Experience that is even renewed because revisiting our collection over time is to rediscover new emotions, to notice details that until now had gone unnoticed, and to contemplate the beauty of the works.

8. Have you ever exhibited your collection outside of Cuba and can you tell us about it?

DC: So far we have not made an exhaustive exhibition of the collection outside of Cuba, although works made by several artists have been exhibited in institutions in Europe such as the Kunsthaus Kannen (Münster, Germany) and the Musée de la Création Franche (Bègles, France).

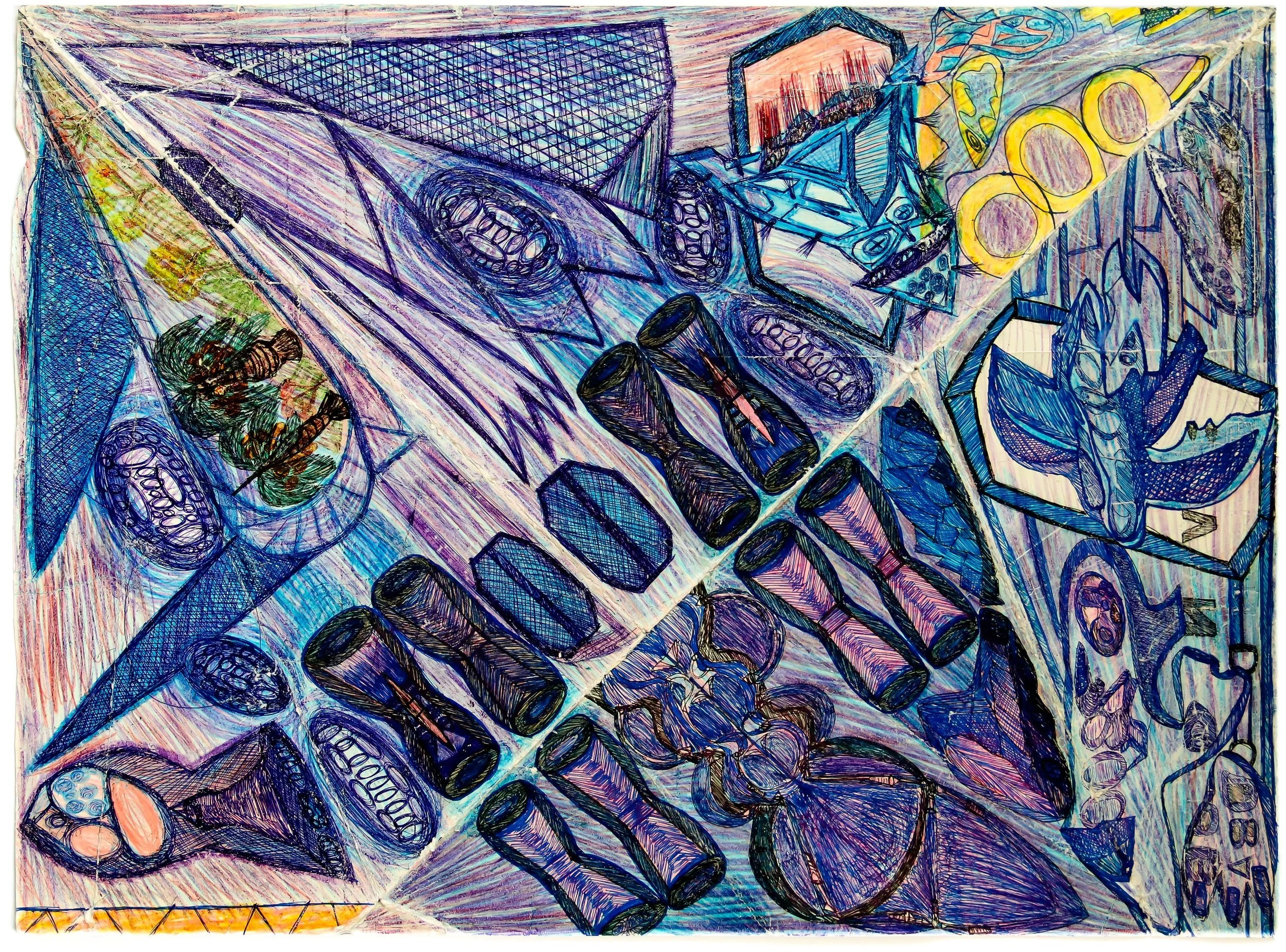

Damian Valdès Dilla. Ballpoint pen and colored pencil on paper, 70 cm x 100 cm, 2015. Photo credits: Samuel Riera and Derbis Campos. Riera Studio

9. You are about to exhibit some works within the framework of the Documenta Festival in Germany, can you tell us about it and what you are going to exhibit? And how did that opportunity come about?

DC: Yes, we are making an exhibition as part of Documenta 15. It will be very significant for Art Brut Project Cuba and a well-deserved recognition – first of all to the work of each of the Cuban artists – but also to the intense work that for nine years we have been doing in pursuit of Art Brut and Outsider Art carried out in our country. The invitation to participate in Documenta 15 was made by the Hannah Arendt Institute of Artivism (INSTAR), an independent organisation founded and directed by Tania Bruguera, one of the main Cuban contemporary artists of wide recognition and international presence. INSTAR constitutes a platform from which research is carried out in the theoretical-practical order for socially committed art and the aspiration of activism to be effective in Cuban society as an agent of social change.

This edition of Documenta has as its central concept, the actions of artistic collectives. INSTAR is one of the organisations invited through the presentation of the Operational Factography project, which shows a counter-narrative of Cuban cultural history through ten exhibitions. Each exhibition exhibits a specific project or practice in Cuba that has been subject to censorship and/or undervaluation by the Cuban government system, integrating various manifestations: visual arts, literature, journalism, cinematographic arts, theatre and music. Art Brut Project Cuba is one of the invited projects, bringing together a collective of artists – who create from their own individualities – marginalised by the systems of official Cuban culture.

The exhibition – which is curated by Tania Bruguera together with fellow Cuban curators Clara Astiasarán and Ernesto Oroza – will show in one of the main rooms of Documenta Hallle. It will be an installation featuring 1,700 individual pieces by 30 artists from Art Brut Project Cuba. Most of the works are two-dimensional, although a selection of objects made by the artist Lázaro Antonio Martínez Durán is included. As a curious fact, two full-scale furniture items, that were built specifically for this exhibition, will also be exhibited following exactly the design embodied in the drawings of another of our artists. This is the largest exhibition of Art Brut Project Cuba to date, in terms of the number of works and artists included, and therefore the most important exhibition of Cuban creators of Art Brut and Outsider Art.

The exhibition of this type of artistic expression within Documenta, has not been at all frequent. The references take us back to Documenta 5 (1972), which under the direction of the Swiss curator Harald Szeemann showed a selection of works by Adolf Wölfli. Undoubtedly, this edition of Documenta has displaced it from its comfort zone, by showing artistic processes - most of them located in or by artists from developing countries - that escape or are undervalued by the traditional contemporary mainstream.

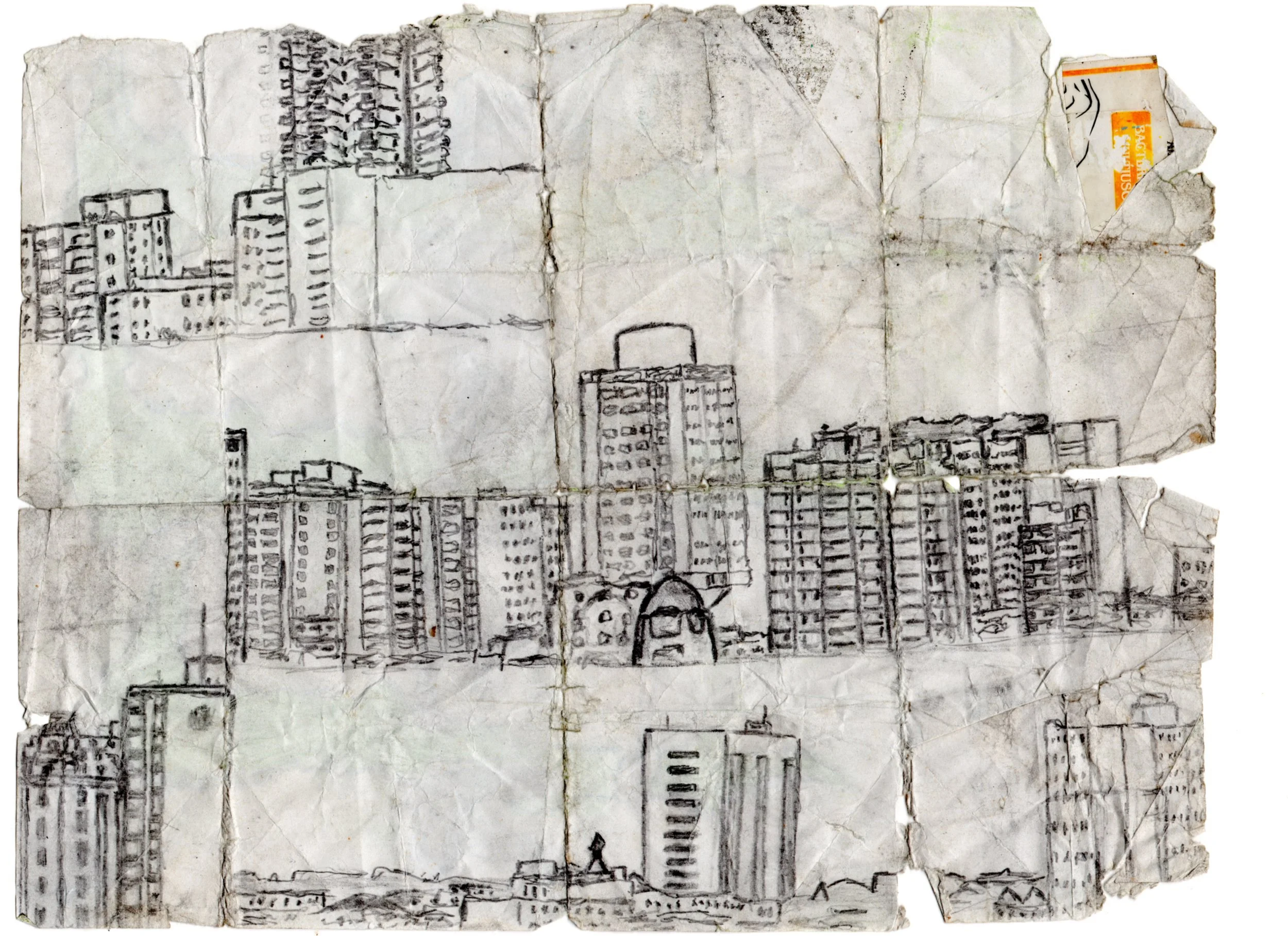

Joan Ramirez Flores. Lead pencil on found paper, 22 cm x 28 cm. Undated. Photo credits: Samuel Riera and Derbis Campos. Riera Studio

10. One of the artists in your studio has been quite successful, Misleidys Castillo Pedroso. Can you tell us about this?

SR: Misleidys was from the first group of creators that we managed to identify, and that we began to support and promote. We met her from another of our artists: Marcos Antonio Guerrero Garrido because they live relatively close, and he and Misleidys’ mother were part of the same Spiritualist study group. It was very interesting to see her drawings, still small at the time, kept in shoeboxes, as if they were her own version of the cut-out dolls that were so popular in Latin America and particularly in Cuba from the 1970s - 1990s. We managed to convince her mother not to remove the figures that Misleidys stuck to the walls of her room with adhesive tape as she finished them, and little by little, she was filling all the walls not only of her room but also of the living room of her home. This is how the figures also began to grow in size – the protective giants as I call them. Since we began to include her works in foreign exhibitions, we defended keeping her works intact as Misleidys stuck them to the wall, that is, leaving the adhesive tape segments as a significant part of her work. Seeing how her work has developed from the beginning and moving through Art Brut Project Cuba to its current representation by a Parisian Gallery, and having been part of that process is very gratifying.

But Misleidys is as important to the current heritage of Art Brut in our country as each of the artists promoted by Art Brut Project Cuba, and as those that we have not yet been able to identify and remain creating. To speak of success, in the traditional way, indisputably implies the consideration of many factors beyond the characteristics of the result of the artistic processes of these artists. Some of them are very subjective factors – as always happens in the art world – shaped by the taste and aesthetic appreciation of certain decision-makers in the processes of visibility and commercialisation of works internationally. Although Art Brut and Outsider Art have their own aesthetics and autonomous processes when considering the evaluation of their creators and their works, it does not escape from similar factors that condition success or not within contemporary art. We always take care to minimise those factors within the group of artists with whom we work. For us, success is seeing how each of these artists develops their creative potential to the maximum, by offering them the confidence that what they are doing is totally right and important – even though most of them are not aware of that reality. For us, success is to see how the assessment of each of them in the family environment changes, like Carlos Javier Garcia Huergo – the first artist with whom we began to work – already in his neighbourhood they do not call him "the madman" now but "the artist". And if we talk about traditional success, we must mention artists such as Carlos himself, with works present in the permanent collection of the Musée National d'Art Moderne du Centre Pompidou, and Damián Valdés Dilla, with works present in the Collection of L ́Art Brut Lausanne and the first Latin American artist to be a finalist in the EUWARD – European Art Award for Painting and Graphic Arts in the Context of Mental Disability competition.

11. A conflicting term at present, but can you tell us about your opinion on the term outsider art, how you feel about it and if there are other words you think we should use instead?

DC: Whenever we talk about the art we promote, we use both the term Art Brut and Outsider Art. We are aware of the semantic differences between one and the other, fundamentally given the origin of each of them and their dispersion and geographical-speaking use. It is even more significant that as Spanish-speakers, we use terms in other languages to refer to this type of creation. Given the limited research work, promotion and dissemination that persists in Latin America – and even in the Iberian Peninsula a term of its own is not used either – there has been no consensus on a term that encompasses this creation in all its magnitude and is not at the same time self-exclusive. Terms such as "marginal" or "bruto" carry implicit a generally pejorative and undervalued semantic load while "periférico" is self-limited to remaining in the shadow of a supposed central art of greater transcendence.

In the context of our country, yes, Art Brut and Outsider Art are consciously excluded by the obsolete cultural system, but we cannot be in favour of using a term such as "marginal" that responds to that imposed reality, and that it is our job day-by-day to be able to modify this. Undoubtedly, there is a need for more research and consensus in our geographical region that allows us to create tools to achieve an inclusive visualisation of these genuine forms of creation and not keep us in a self-censored "ghetto".

The use of one term or another is undoubtedly complex and often responds to interests of different kinds, even outside of art. Even Jean Dubuffet himself reclassified part of his Art Brut collection in the late 1960s, giving it the name "Neuve Invention" years later. So, the concept of Art Brut during all these decades had its readjustments by its own creator and main promoter at that time.

Then, the definition of Outsider Art provided by Roger Cardinal also led to the emergence of many other terms – art singulier, visionary art, intuitive art, art en marge, art hors-les-normes, art modeste, création franche, art inventive, mediumistic art, etc. Outsider Art's own term over the years has become a kind of inclusive umbrella for self-taught creators with a work of peculiar characteristics and content far from formal art, which evidently accommodates different interpretations and subjective applications.

With the development and evolution of our project and the acquisition of experience and visual training regarding this type of art, we manage the essential conditions of Art Brut exposed by Dubuffet, and also the first vision of Outsider Art, not rigidly, but evaluating each creator in their own context and each work in particular.

We consider it an ethical practice to keep the creators with whom we work aware of the exhibitions and recognitions of their works, that they are happy with this. Even in relation to the acquisition of their works. To ensure that these people can obtain an economic benefit, direct or indirect, for what they do with so much passion, is also one of the goals of our project. We are not afraid to call them artists, even if many specialists consider that an artist implies a conscious attitude towards the way of making art.

12. Is there anyone within this field who you feel has been especially important in paving the way to where the field is now?

SR: I think it would not be fair to single out one person in particular above the work that many have done and continue to do today. Even to mention Dubuffet, who undoubtedly opened the doors to the development of knowledge and appreciation that we have today, would not be completely fair to others who accompanied and supported him in his task, and to those who even before him began to glimpse the potential of this type of artistic creation. I believe that the interest in Art Brut and Outsider Art still grows significantly internationally among art specialists, critics, heads of cultural institutions, academic artists, gallerists, collectors, ethnographers, sociologists, students and in the general public.

Marcos Antonio Guerrero Herrera. Colored pencil and ball point pen on found paper, 49 cm x 56 cm, 2017. Photo credits: Samuel Riera and Derbis Campos. Riera Studio

13. Are there any artists you still want to add to your collection? And is there an artist or work that you haven't bought and that, looking back, you wish you had?

SR: As we mentioned, our collection is constantly growing from selected works by the artists with whom we currently work, as well as with the incorporation of works from deceased artists. Our work is constant in the identification of new potential creators from the different regions of the country. It is precisely in the provinces far from Havana where we think we still have a long way to go in the search for these potentials. So indisputably, new artists will continue to be added to Art Brut Project Cuba and the collection. On the way during these nine years of existence of the project also - but mainly in our beginnings – we missed the opportunity at certain times to incorporate works by some creators that for various reasons we were later unable to do so.

It is also curious to mention that on very few occasions we have met creators whose attachment to their productions is so strong and intimate that they have not allowed us to include them in the collection. Yes, in those cases it would have been important to add a selection of their works to the collection, but it has not been possible for us. On the other hand, the physical space we have for the storage of the works is limited, which makes it difficult for us to acquire large sculptural works. We have had excellent pieces of this type on display, but it has not been possible for us to maintain them in our collection, once these exhibitions are over.

14. Is there anything else you would like to add?

SR: Just to thank you once again for the possibility of sharing our experiences and opinions from a context that in itself generally locates us, and is worth the "outsider" redundancy of the field itself in which we move through both internal and external elements, many of which we have already addressed here. Our thanks also on behalf of all the artists of Art Brut Project Cuba.

NOTES TO TEXT

(1). Fidel Castro Rúz. Meeting with Cuban Intellectuals. National Library of Cuba. June 16, 23 and 30, 1961. Havana, Cuba. Shorthand versions. Department of State. Republic of Cuba.

(2). Samuel Feijóo was a self-taught multifaceted artist and writer. He was a promoter of the movement of popular artists in the central provinces of Cuba during the years 1960 - 1980. Under the name of “Grupo Signos”, he brought together a group of creators, most without academic training. He was invited by Jean Dubuffet to exhibit in Lausanne works by different artists of this group. The exhibition "Art Inventif a Cuba" was presented at the Collection del'Art Brut in Lausanne in 1983.

(3). The first independent exhibition space was Espacio Aglutinador, created by artists Sandra Ceballos and Ezequiel Suárez in their own residence, with the aim of somehow disseminating another point of view regarding the plastic arts in Cuba. It is a space more than anything curatorial that responds to the ideas of those who organise their events.

August 3, 2022