Shari Cavin and Randall Morris, New York - MEET THE COLLECTOR Series Part Thirty Two

For part thirty-two of my ‘Meet the Collector’ series I chatted over zoom with Shari Cavin and Randall Morris that make up the Cavin-Morris Gallery in New York. They were sitting in different parts of their apartment, but could hear each other and so could add things in to each other’s viewpoints. I have met these two on numerous occasions and had the delight of being on a booth next to them at the Outsider Art Fair in Paris in 2019. Read on to hear more about their lives and how they got to where they are now …

Shari Cavin and Randall Morris at the Outsider Art Fair

1. When did your interests in the field of outsider/folk art begin?

Shari – Randall was raised around self-taught material and I was raised with ‘you don’t put anything on your walls and you certainly don’t use scotch tape, and don’t mess up the paint’. I came to love art because I have danced all my life, so it was natural to learn certainly about music and art. I got interested in self-taught after meeting Randall.

When did you meet Randall? I met Randall in 1976 shortly after I came to New York and we got married in 1979. And where were you before this? I was in Santa Barbara, California. I went to the University of California, San Diego where I was going to be a scientist. I really wanted to study virology. However, my intellect was really geared towards dance, literature and music. It was the era of the assassination of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X . It was the era of the Vietnam War. There was extraordinary social unrest, so was no way I was going to sit in a lab hunched over a microscope. I needed to be involved. In my second year I transferred to UC Santa Barbara and that’s where I studied English Literature and Dance.

Randall – My father collected Haitian art to a degree in the forties, so I grew up with the art from the very beginning… especially the work of Georges Liautaud and Hector Hyppolite. I never saw myself as a collector until I met Shari, as I was going to be a marine biologist. When the demonstrations of 1968 in New York happened, everyone got an automatic grade of pass which was not good for where I was going to school for marine biology. I switched to literature. I was always a writer and literature was what I wanted to do anyway. From the time I was 15 onwards I had books on naïve and primitive art and tribal stuff, so I grew up surrounded by it. Then I met the poet Kenneth Rexroth in Santa Barbara and became part of his circle of students. He taught that a Native American or Pigmy chant was also world literature, and I felt that the seeds of Cavin-Morris were sown right there.

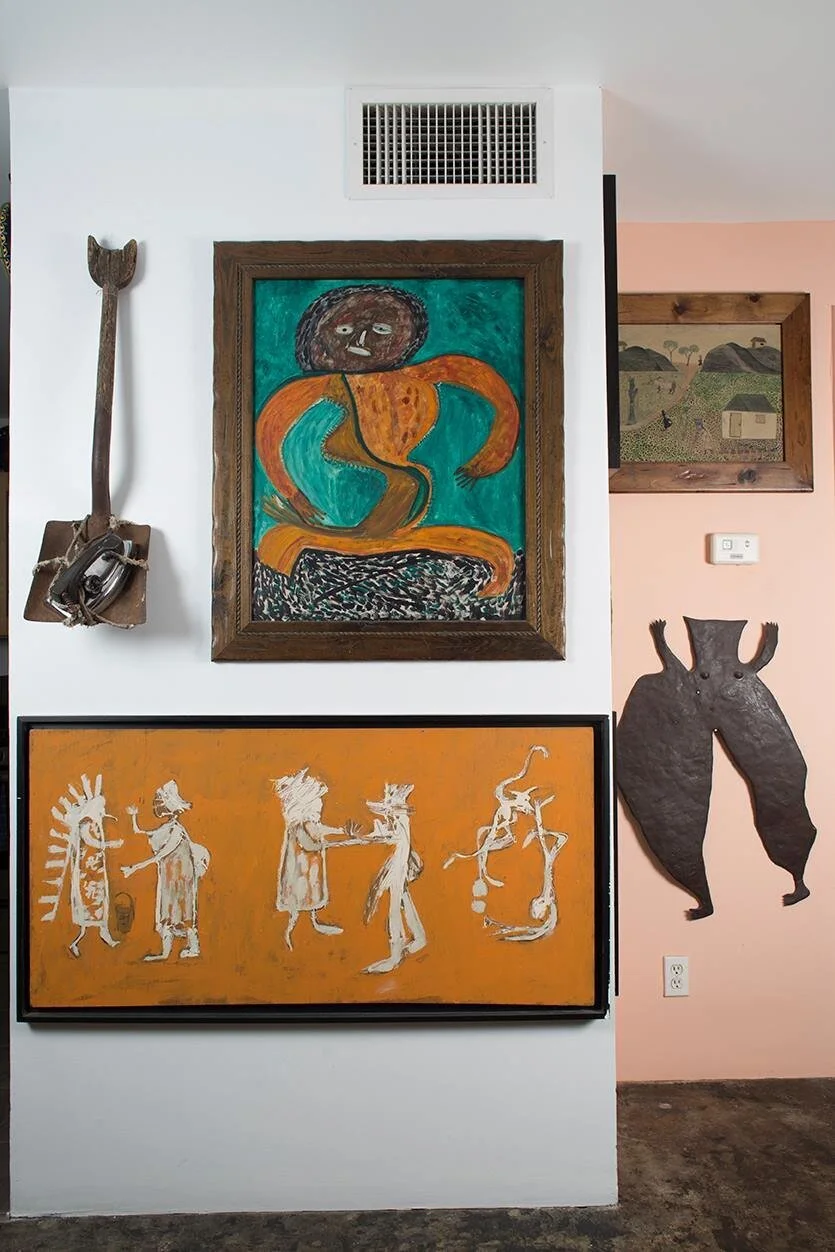

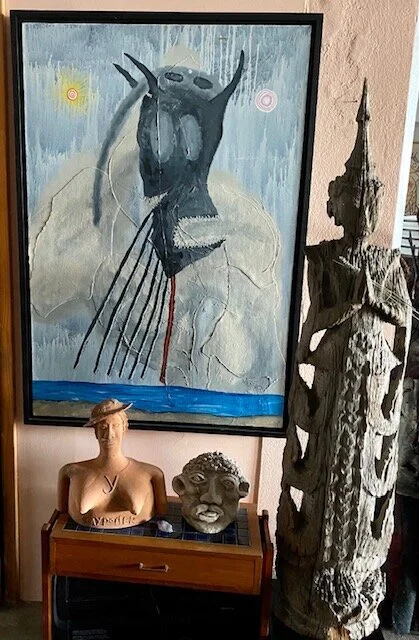

Inside Shari and Randall’s apartment

2. When did you become collectors of this art? How many pieces do you think are in your collection now? And do you exhibit any of it on the walls of your home or elsewhere?

Shari – I am trying to think about when we started. Randall’s dad gave us a piece of art or two after we got married. For our honeymoon we went to Haiti and we met Georges Liautaud. We bought sculpture from him on that trip. Back in New York, one of the first pieces we bought was a fake Mexican mask. We really paid a lot for it, even by today’s standards. When we realized it was fake, it was an enormous wake up call. It was an important lesson about collecting, that to be serious at it took studying. That included speaking with other dealers who were experts and watching them look at art, and listen as they spoke about it, including why they thought it was important and why they thought it was authentic. We also learnt from them how to see if something wasn’t right. It was more than just the material of the object, but the way a piece came together. We learnt to develop our intellectual dialogue as well as our visual dialogue. With enough of both, our intuitive sensibility started to develop. That carried over to the self-taught material. We had more experienced dealers as friends who generously shared their insights with “the kids”.

Randall – We started with Mexican masks and pre-Columbian art and Haitian art, but we were too late for the first generation of Haitian art. A lot of the collectors then were only paying attention to the first generation of artists. We started focusing on those works of art by lesser known artists. We figured that what we would do would be to go to Haiti, as by then we had the contacts, buy the work and then sell it at Sotheby’s Park Bernet. The plan was that the profits from those sales would allow us to purchase other works that we thought were excellent. Our second trip to Haiti was our buying trip, with this “business plan” in mind. The day after we stepped off the plane, Sotheby’s Park Bernet discontinued their Haitian art auctions. We had a lot of inventory, which became the beginning of the gallery. We were actually very successful with it.

About six months after that, we found Bert Hemphill’s book (Twentieth Century Folk Art and Artists) at Strand. Going through it, we realized that what we loved about Haitian art also existed in America. We knew about naïve art as it was presented in Europe, but less about the art in Bert’s book. We were not tuned into art brut yet. We came to it from a purely American perspective. That was the beginning of our involvement with self-taught art in a larger context.

I worked at what was then Ricco/Johnson Gallery, helping to support our then ‘by-appointment’ gallery. Ricco/Johnson predominantly sold folk art, so that was another education. What I really learnt from working with Roger Ricco for two years was how to light and present work in the best possible way.

It was a messy beginning. Because of our friendship with Bert we met a guy who had dozens and dozens of early Howard Finster pieces, which he consigned to us. These early works, dating from 1976 – to about 1979 were in great demand and those sales helped move the gallery forward. Bert Hemphill became one of my closest friends. This opened up the whole American field to us. We were very conscious that in America it was still called folk art and we were not comfortable with that, and still annoy people with our vehement separation of folk and art brut.

How many pieces are in you collection now? It is probably close to 1,000, but we stopped counting at 4. The masks on the feature wall in our home are Mexican, that we have been collecting from the beginning. There are around 150 of those. We now collect Nepalese masks as well. And of course Art Brut.

Inside Shari and Randall’s apartment

3. So I recently interviewed Monty Blanchard and he mentioned that he started buying art from you when you were selling it from your home, perhaps in 1985. Is that correct? And how long did you do that for before you started your gallery and why did you want to set it up?

Randall – We started selling out of our home very early on, maybe 1979. We moved from our home to our first gallery in 1985. Between 1980-1985 we had a private gallery called Ethnographic Arts Incorporated. We saw this work as part of the Ethnosphere, a phrase coined by Wade Davis. We knew all the players in the field by 1985. We went public when the co-op of our building (which included a blue-chip dealer or two, as well as a significant collector) threatened to sue us for dealing from our home. It was, despite the drama of the moment, one of the better things that ever happened to us.

Shari – It was wonderful having Monty and Anne around the corner from us. We do go way back. Anne was pregnant with her third daughter, Cordelia, when I was pregnant with our daughter, Simone.

And how many times has you gallery moved? We started ‘by appointment’ only. We had two ‘by-appointment’ homes and 3 different gallery spaces. So we have moved 5 times. We have been in our current gallery space nearly 15 years.

So what made you want to set up a gallery?

Randall – We wanted to handle as much work, as close to the source/the artist as possible. There were artists we wanted to see and be directly connected with it, plus we wanted to introduce new work, and we wanted to upgrade the way non-mainstream art was being presented at least in North America. We again did not want to present it as folk art, but show it as contemporary art, but not as mainstream CONTEMPORARY art. It is different and it will always be, but it deserves the same dignity, seriousness, and same formal presentation as Contemporary Art.

Inside Shari and Randall’s apartment

4. How has your gallery changed over the years and has the focus of what you sell shifted during that time?

Shari – At its core it is still the same now as it was in the early days. With our first public gallery we were very fortunate to have those early Howard Finster paintings, as well as other terrific artists. We worked closely with John Ollman for a while also, benefiting from his generous eye and business acumen. We not only showed the work of non-mainstream artists, but contemporary artists too. Sometimes we showed their work together in themed shows and sometimes we gave contemporary artists their own show. It was important for us to show the self-taught artists with the same respect given to contemporary art. But the contemporary art we showed with it had a definite affinity. That included the affinity of the hand, which was important for us. For example, we did an exhibition called The Apocalyptic Edge, with four enormous double-sided Darger’s, Charles Burns’ original drawings of Big Baby, a wall-sized painting by Don Colley, and some of Tony Fitzpatrick’s first slate drawings. Another exhibition had 8 enormous “roadside” crosses by Jimmy Roche; in another exhibition we had a huge, fabulous Petah Coyne sculpture hanging from the ceiling, another, Rachel Mendieta created an Ana Mendieta sand sculpture for us. It was all work that resonated with what we loved about the self-taught material. It was that material—the non-mainstream–that took the lead.

Randall – I would say the only shift in focus that I can see is that we decided not to specialise in tribal art, which we were also showing at the time because we could not afford to present the quality of the tribal art that we wanted to show. In other words, we knew what the best and the greatest was and we were showing the new and the best and the greatest in the other field that we were involved in, so if we couldn’t do that with tribal art, we decided that we didn’t want to pursue it. We still have a few pieces now, which I still write about and show to this day. We also show our taste in contemporary ceramics and ceremonial masks of the world, in addition to Art Brut.

What are your roles in the gallery?

Shari – Randall says he is research and development and I am chief operating officer. So I say I am in the trenches and Randall is researching the next shows, processing intellectually, curating and looking at the whole concept of what it means to move forward in this field. He does the social media too… I don’t touch social media. I also do art appraisals, some through the gallery and some separately. My expertise is in (that word) Outsider Art. I am one of two certified people in the US for this category of art. My expertise is the impossible–the artist built vernacular environments. Those would be, for example, Eddie Owens Martin’s Pasaquan, in Buena Vista, GA; The Garden of Eden in Lucas, KS; Vollis Simpson’s Whirligig Park in Wilson, NC. They are all over America and they are certainly in Europe. The first European site that pops into my head is the Palais Idéal by Postman Chaval in Hauterives, France.

5. What is it that draws your eyes away from contemporary art to outsider/folk art? Or do you collect both?

Shari – For me, it is the show of the hand that I find extremely important. I have said before that I don’t find much cynicism or sarcasm in the work of self-taught artists. There is a genuineness, and there is irony. There are contemporary artists who also show the hand, which is often turned to justifiable political purposes. There is something about that hand that appeals to me immensely. Perhaps it is the immediacy – the connection between the impulse and the action — unedited — that I find so appealing. I do find minimalism extremely beautiful, but it can also be intellectually driven and rather icy. Much of contemporary art is about artists responding to other contemporary art, which becomes a knot of an argument and it leaves me asking why did you make this work? There is something about self-taught artist’s work that makes you understand why they made it on a very intuitive level. You listen to yourself while you look at it and you get it.

Randall – We don’t necessarily collect both, but we have examples of both. But we absolutely don’t see that one is more superior. We are very aware of mainstream art and artists. There is just an immediacy that is involved with the works that we do show and collect that fits with our focus. A lot of our friends are contemporary artists, so we are in that world no matter what. It is funny because people always assume that if you sell Art Brut, then you don't know anything about contemporary art. We are just as savvy as other people and we made a choice. We don’t collect or sell folk art.

Inside Shari and Randall’s apartment

6. A conflicted term at present, but can you tell us about your opinion of the term outsider art, how you feel about it and if there are any other words that you think we should be using instead?

Randall – A long time ago Didi Barrett was involved at the Folk Art Museum as the editor of the then publication called The Clarion. She coined a phrase that other people have since claimed, but she was the first to use: term warfare. We have not used the term outsider for years now. We used it for a few months at the beginning of our public gallery days because we did not want to use the term 20th century folk art. It was called that fanatically. Everyone denies it now. But the first dealers in folk art slowly began moving into this other term. That includes Phyllis Kind and a whole bunch of other wonderful dealers. But after a long back and forth and a personal friendship with Robert Farris Thompson (often labeled a feral scholar) who is a Professor Emeritus at Yale in the History of Art and African American Studies. He’s also the Master of Timothy Dwight College at Yale. We saw that the term ‘outsider’ was completely wrong as a label. It has become a brand and I understand that – it is no longer really debated. But it describes an infrastructure around the field – fairs, dealers and the American approach to the field – for better or worse, but it does not define the field. But we don't use it. It in inadequate and there are ramifications… there are political and social reasons that marginalise people as outsiders already. Art Brut for example, though not perfect, describes the art and not the artist. And that’s what we need to do… talk about the art. Non-mainstream is very general and it describes the intentionality of whom and for whom the work is made. This field is different again from mainstream art. I have said for years, it all comes back to the intentionality of the artist.

So when you do things like the Outsider Art Fair how does it make you feel to exhibit under that label? It doesn’t put you off doing it?

Randall – I don’t describe the artist’s as outsider artists. So in my head it is easy to turn things around, like you don’t always buy hardware in a hardware store. Yes, they call it the Outsider Art Fair, but that doesn’t mean that I sell outsider art in it. It is just a brand. I guess that it’s the best substitute word for another word that may never be found. We focus on the artists and the art they create.

What do you think of the term outliers?

Randall – I was hoping you wouldn’t ask me. It’s a terrible word. You have the artist’s; you have the dealers; the curators and the academics. They are what I call the infrastructure of the field and they are constantly trying to plant a flag in the beach of the art claiming it and then showboating it. So this is what happened with outliers. There were great works in that show and incredible artists and the works have lasted longer than the term itself. I keep thinking of stagecoach robbers at the side of the road outlying and watching people go by. I think it fell flat on its face. But the quality of the show was still great.

Inside Shari and Randall’s apartment

7. What style of work, if any, is of particular interest to you within this field? (for example is it embroidery, drawing, sculpture, and so on)

Shari – I do love art that is extremely expressionistic, and I do love art that is extremely detailed, or what is generally called obsessive. So at this point I don't think I have a particular type that I like. I bet Randall would be able to say ‘oh I bet Shari would like this’ and he might be able to say why, but in my mind I don’t process it that way. You know at a certain point if you have studied enough and you have looked enough and you have questioned enough and you have argued enough and you’ve been in enough artist’s studios and homes, then at some point you have absorbed that material and the boundaries have disappeared in the absorption, so it’s a part of what you find beautiful — riveting, compelling. I love textiles, I love embroidery, I love the idea of contemporary embroidery that says outrageous political things, I love brutal massive metal sculptures, I love ceramics, and all of these are also a part of this field. There are certain things I really don’t like, but I find that variety is what I like best.

Randall – I love art that talks about culture on some level and has a meaning to it. Even if the work is from an institution, it still reflects culture. I can tell you what I don’t like which is whimsy. Nothing bums me out more than a piece of art that makes you chuckle once. You are meant to heh-heh at every time you look at it. I don’t like art that is funny for the sake of being funny. We gravitate to the art that comes from long, incredible, cultural history; Native-American, African American, non-western, art from different immigrant nationalities and Americas. That sort of thing. I just don't like art that has a funny face and expects me to guffaw.

Inside Shari and Randall’s apartment

8. Would you say you had a favourite artist or piece of work within your collection? And why?

Shari – We are fortunate in our home to have lots of different places where we can sit. If I am sitting on the couch by the window, I have view of the wall of masks and an incredible painting by José Bedia, and work by Bessie Harvey. If I am sitting at my piano I have Zemánková, Plny, Doi, Van Mannen. I have a Staëlens sculpture on my right and a Georges Liautaud on my left. The top of my piano is filled with miniature goddess figures from all over the world. If I am upstairs at my desk, I have a wall of small Zemánková’s surrounding a big Zemankova and my favorite masks behind me. Off to the side are paintings by Melvin Edward Nelson, Joseph Lambert, and J.B. Murray. There’s a small photograph of Merce Cunningham leaping taken by Barbara Morgan tucked in a private corner near my desk. There’s anonymous Indian tantric drawings mixed in. Near the television, is a place where we look at art and discuss it and process it. Randall’s desk has its own wild surroundings too. So the answer to your question is, not particularly. There are some very small insignificant pieces that give me great joy when I look at them, which I do daily. The first thing I look at in the morning when I wake is a painting called Divina Pastora by José Bedia. I try to receive her blessing each morning before I get up. There is a very small Liautaud dog on my bookshelf that I pick up every day as I like it so much.

Randall – We love everything in our home. It is hard to build those hierarchies. Every piece is a mutual journey for us because for almost everything we both agree on its right and power of being here. We listen to the person who says yes and not the person who says no, as that person might see something in that piece that the other didn’t. But when it is here it joins the other pieces and it becomes family. The collection itself decides.

Do you ever hate any pieces that the other person has bought home?

Shari – There are pieces in the collection that Randall might like more than I, but we don’t hate any pieces here. The first argument we had as a couple – it was very defining for us – his father had been to Haiti and bought back a nasty wax sculpture that was about 20 inches long and 10 inches high with a skull carved in the center and something else on either end. Randall was raving about it. I said to Randall it is ethnographically significant and I get it, but I think it is just butt ugly and I don’t like it.

Randall – It seems to have disappeared somewhere over the years though!

Shari – Randall will appreciate the cultural significance of a piece and why it is important even if he doesn’t aesthetically love it. And I am the same. I always take art back to the place where the artist made it and think about the intentionality. And the visual. I come from years of dancing. I look for rhythm, composition, line, and something that makes a piece sing, that is not about technique.

Randall – And we both tend to appreciate its formal qualities. We don’t just like it because of the cultural thing but it has to answer other questions that we cannot verbalise… like what is its significance to the maker? How formally does it hold together? Are we excusing anything in the piece because we like the culture of it? So now with the quarantine thing, I walk around and look at pieces we bought 20-25 years ago and think ‘wow this thing is good’. And I realise we internalize the quality issue. We don’t speak about it, but we have done it long enough now and we both seem to be on the same page. And what it really comes down to is good, better or best. And I listen to Shari on that because she has a more critical eye, so between my expressionism and her minimalism is a good viewpoint between us. There has never really been anything to make us unhappy about pieces coming into our house. It is about a conversation. Something Thompson said: “you see me give a one-word answer or passionate declaration now but what you don’t see are the decades and decades of experience that feeds those answers.”

Shari – We bring art home for approval and we put it on the wall and if it bombs – if it cannot speak with the other art on the walls – out it goes. The collection becomes the judge of what can come into it.

9. Where would you say you buy most of your work from: a studio, art fairs, exhibitions, auctions, or direct from artists?

All of the above.

Inside Shari and Randall’s apartment

10. Is there an exhibition in this field of art that you have felt has been particularly important? And why?

Shari – For us, it started with ‘Black Folk Art in America’ – it was seminal. It was a mind boggling ground breaker.

I just bought the book actually as so many people highlight this as a great exhibition.

Shari – There are things you’ll love in the book and things you won’t… but it started a very necessary dialogue in this country. In Philadelphia there was a Martin Ramirez show at the Moore College of Art that was extraordinary. In LA there was ‘Parallel Visions’ that was vilified, but in retrospect it was pretty good. It bought together untrained artists and contemporary artists and discussed how one influenced the other. A lot of it was about how contemporary artists were influenced by these other extraordinary artists. And then around 30 years ago we saw the Hilma af Klint show at P.S. 1 that just blew the top of my head off. It opened my eyes to this whole other idea of true spiritual work of art, not religious, but spiritual. I want to give a shout out to the work that has been done at the John Michael Kohler Art Center in the work they have done to preserve artist’s environments and presented them there. There was a show called ‘The Road Less Travelled’ where there were major installations of artists’ works including Emery Blagdon, the Rhinestone Cowboy, Gregory van Maanen, Eugene von Bruenchenhein, Nek Chand, and Dr. Charles Smith. These are major artists’ environments that were bought into this one space. It was accompanied by several days of lectures and discussions as to why these environments were important to preserve and save. Those exhibitions and the solo exhibitions were super important too, including Wölfli at the American Folk Art Museum, and Leslie Umberger’s Bill Traylor show at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Valerie Rousseau has single-handedly brought major art brut exhibitions to the American Folk Art Museum. For many Americans, these exhibitions were their first exposure to Art Brut.

Randall – The Corcoran show, the AVAM shows, the Traylor show at the Smithsonian, Halle Saint Pierre shows in Paris, abcd shows at the now shuttered Maison Rouge in Paris, the way the Quai Branly Museum in Paris approaches ethnographic exhibitions. They have a smaller gallery space where they show art of parallel interest. We saw a contemporary Aboriginal art exhibition there one year, and the next year there was a show on racism towards African Americans in the United States that was extremely powerful. Of course the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne.

11. Are there any people within this field that you feel have been particularly important to pave the way for where the field is at now?

Shari – I think that for me Bert Hemphill was essential. He was the most open human being I have ever met in my entire life. It didn't matter whether it was art or food. We went to a dim sum place in Chinatown with Bert. Our place of choice had a very loud wedding party there, people singing full throttle – he wasn’t phased! He laughed and said “isn’t this marvelous”. So like Bert! There are scholars whose work I appreciate, including Leslie Umberger and Valerie Rousseau. I do think that the enthusiasm with which Roberta Smith and Jerry Saltz have written has been critical in getting the general public to take this art form seriously. Robert Farris Thompson has been essential. And probably many others I cannot think of right now.

Randall – Robert Farris Thompson wrote the book ‘Flash of the Spirit’ and that book was so important, it may have been instrumental in giving the Corcoran Exhibition impetus to have been conceived. All the people that worked on that show were influenced by Robert Farris Thompson. We were so fortunate to have become close with him. He came and lectured at our first gallery, and I lectured in his class at Yale. He just got it. He wrote on Basquiat and other African American artists like Traylor. He used the term outsider to get a perspective on terms.

Roger Cardinal, Barbara Safarova, Leslie Umberger, Judy McWillie (she turned everyone’s head onto the African American South artists), Laurent Danchin, Valerie Rousseau, Colin Rhodes, Lucienne Pierry, Sara Lombardi, Terezie Zemánková, and others.

Inside Shari and Randall’s apartment

12. Is there anything else you would like to add?

Randall – I want to talk more about the focus of the gallery and the direction that we go in and how we focus what we do. In Art Brut etc., we are especially interested in spiritual art and the spiritualistic aspect. In ceramics we are really into textures and the transformation of texture. And with the masks we tend towards the spiritual and shamanistic. Everyone seems to be doing spiritualistic shows now, but we were the first to do these shows 10 and 20 years ago.

I am currently working on three projects. One is a book on American Art Brut as no one has presented it that way. In doing that I will be able to bring together Europe and the United States.

Another project is Art Brut and the shamanistic impulse. I got so tired of artists telling me they are shamans, or writers calling artists shamans. I wanted to do a book that shows the genius in the art. I believe the impulse to be spiritual and shamanistic is in every human being and it can be in the artist, but a shaman is trained in the culture year after year and that is where their art comes from, so I want to do something that shows the difference. And then this final project is up in the air, but I was supposed to curate a two-floor African American show at Halle Saint Pierre in Paris. I am not sure if this will happen now. No one has done a show of all of African Americans, including North and South America. Each place is normally kept separate and I would be mixing the south, with the north, with the Caribbean and so on.

Shari – I would add that both of us are drawn to work that feels as though nature is living through it. That there is some organic spirit in it. I feel that in spite of everything else art will be made because it has to be made and when I feel that genuine impulse and immediacy in a work it is very moving to me.

Randall – There is a section of mainstream art. We call it non-mainstream. It is not supposed to be negative. It is just about the intentionality. But there is a section that I am calling eccentric mainstream and that is the section where mainstream touches Art Brut. The artists like Simone Pelligrini and others who are completely aware of Contemporary art and trained, but who have chosen to work in a non-classical trained way and have re-built themselves to work in another way. Someone like Basquiat and Keith Haring. All those who are very aware of it and the mainstream. I think these artists work well shown together alongside non-mainstream artists.