Michael Bonesteel, Chicago - MEET THE COLLECTOR Series Part Twenty Three

I have read about the work of this week’s collector both online and in his books. He was introduced to me by John Maizels (Editor of Raw Vision). Michael Bonesteel is part 23 of my ‘meet the collector’ series. Read on to find out more about Michael’s fascination with the one and only Henry Darger and his other passions in life…

Michael Bonesteel, photo credit Richard Pearlman

1. When did your interest in the field of outsider/folk art begin?

In the late 1970s, I was working as the publicity director for an art museum and in its library I found a copy of the catalog for the first Henry Darger exhibition at Chicago’s Hyde Park Art Center in 1977. In the vernacular of that era, it blew my mind. I had never seen any art as astonishing as Darger’s and it was that event, coupled with an exhibition called “Grassroots Art Wisconsin” organized by the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in 1978, that I became fully aware of the field of non-mainstream art.

2. When did you become a collector of this art? How many pieces do you think are in your collection now? And do you exhibit any of it on the walls of your home or elsewhere?

I began collecting affordable self-taught art in the 1980s. I now have several hundred works of by both trained and untrained artists. Most of the former works were given to me by artist friends and yes, I exhibit my favorites on the walls of my home.

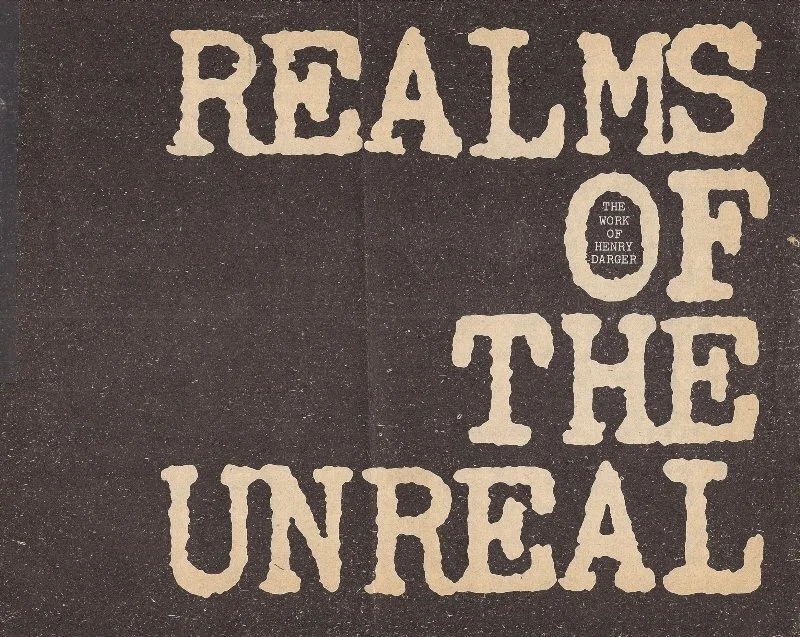

Realms of the Unreal The Work of Henry Darger, Hyde Park Art Center, Chicago, catalog, September 25 through November 5, 1977

3. Can you tell us a bit about your background?

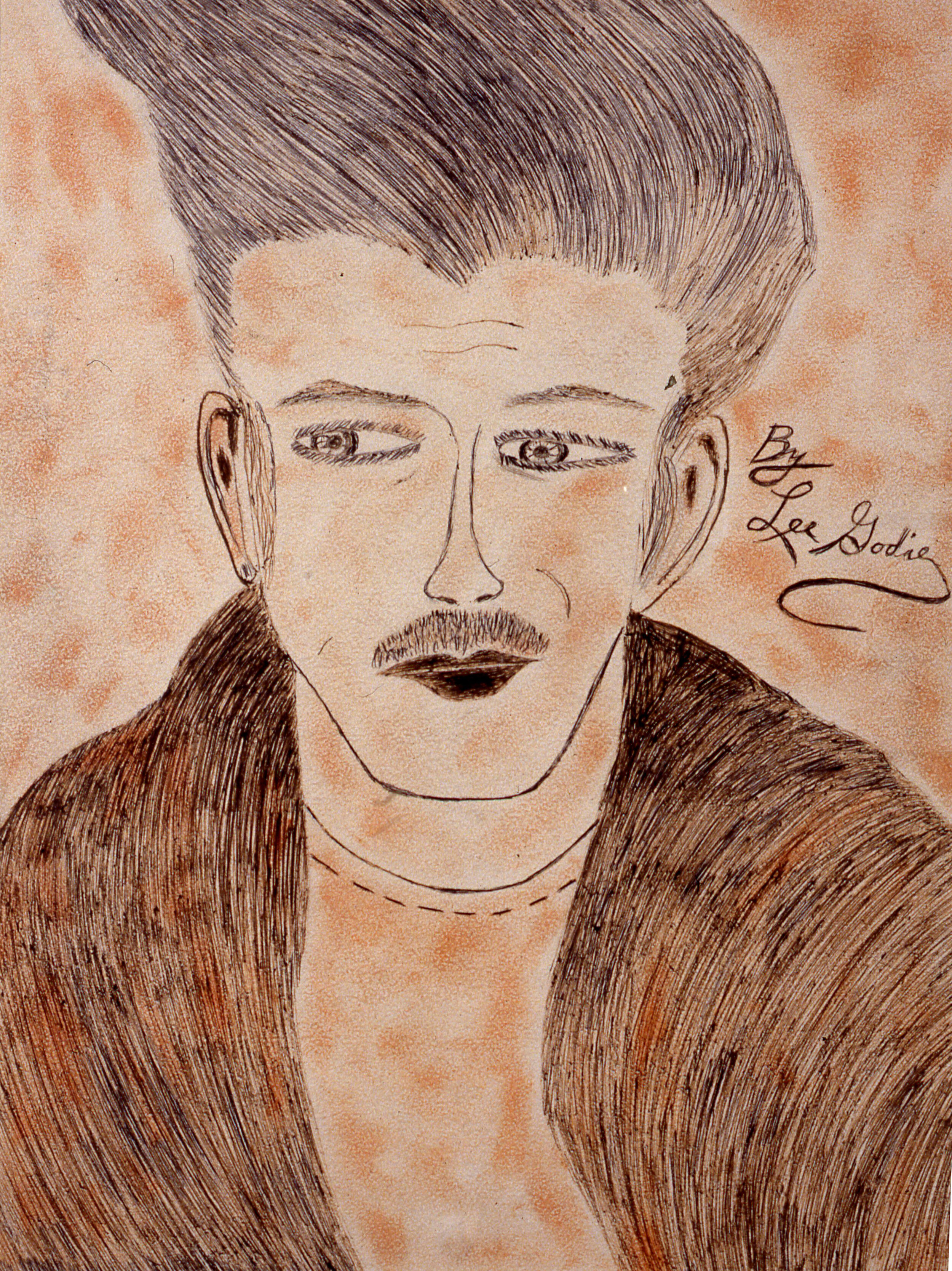

I was born in Chicago, Illinois and went to undergrad and grad schools in Wisconsin, majoring in English literature and creative writing, with a minor in psychology. As a young man I wrote and published poetry and did readings accompanied by folk and jazz musicians beginning in the late 1960s. These morphed into performance art pieces presented in art galleries by the early 1980s. From 1974-1977, I edited a newsletter for an alternative gallery and began publishing art reviews in area magazines and newspapers. In 1980, I was hired as a bureau chief for the New Art Examiner in Chicago, started writing art reviews of Chicago exhibitions for Artforum and other art publications, then became a Chicago correspondent for Art in America. For the latter, I broke stories nationally about Midwestern outsider artists Darger, Lee Godie, Joseph Yoakum, Eugene Von Bruenchenhein and others. For the better part of twenty-seven years, I worked full time as an art critic and arts journalist for a suburban Chicago newspaper chain, eventually becoming a managing editor. By the late 1980s, I was still writing about mainstream art for my day job, but devoted my freelance writing to the field of outsider art. I worked part-time as an adjunct professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and taught classes from 2003 to 2017 on the history of outsider art. Since 2010, I have been a contributing editor for the British publication Raw Vision.

4. You have written a couple of books about the infamous outsider artist Henry Darger. Can you explain to us what drew you to him in the first place and why you have written so many things on this great artist?

Learning about Darger’s work introduced me to the field of non-mainstream art in general, but over the years he and his work have remained my primary obsession. His vast oeuvre appealed to my interests in literature as well as visual art because Darger’s artwork extrapolated upon his two unpublished epic-length novels. The world-building mythology he constructed, colored by his conflicted Catholicism, and the fact that his personal and artistic lives blended inextricably, attracted my interests in psychology and spirituality.

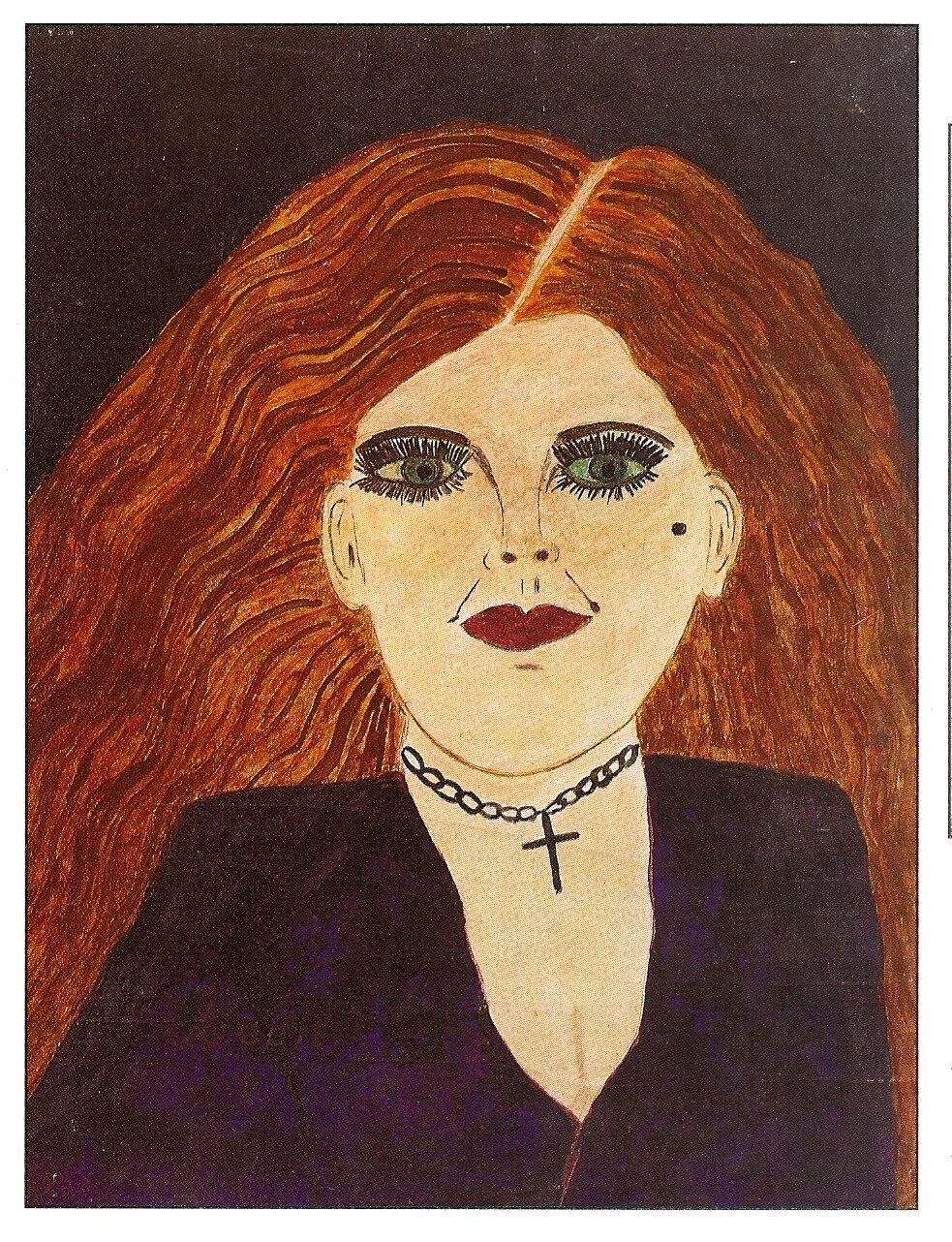

Lee Godie _The Girl in the Miror [sic],_ mixed mediums on canvas, 24 x 18 inches, 1970.

5. What is it that draws your eye away from contemporary art to outsider/folk art? Or do you collect both?

As mentioned, I have collected both but my predominant passion since the late 1980s has been for outsider art. Changing trends and fickle fashions in mainstream art began to annoy me to the point that by 1990 — when the mainstream and academic artworlds began to sink inexorably into deconstructionism and neo-conceptual art — I devoted my interest and writing almost exclusively to outsider and non-mainstream art. My predilection is for art brut (“raw art”), the most intense and extreme expression within the non-mainstream field, because to me it reflects most faithfully the deepest glimpse into the artist’s psyche.

6. What style of work, if any, is of particular interest to you within this field? (for example, is it embroidery, drawing, sculpture, and so on)

I most enjoy two-dimensional work: painting and drawing. Particularly those works which contain both image and text.

7. Where would you say you buy most of your work from: a studio, art fairs, exhibitions, auctions, or direct from artists?

Back in the day, I purchased work from galleries or directly from the artist. I am semiretired now and living very frugally, so I can no longer afford to collect work. In fact, as of late, I’ve been de-accessing and selling off some my collection. Several years ago, upon the death of Minneapolis art brut collage artist Richard Saholt, I inherited his entire body of work. I have been able to donate much of it to institutions such as the American Folk Art Museum in New York and Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art in Chicago, among others.

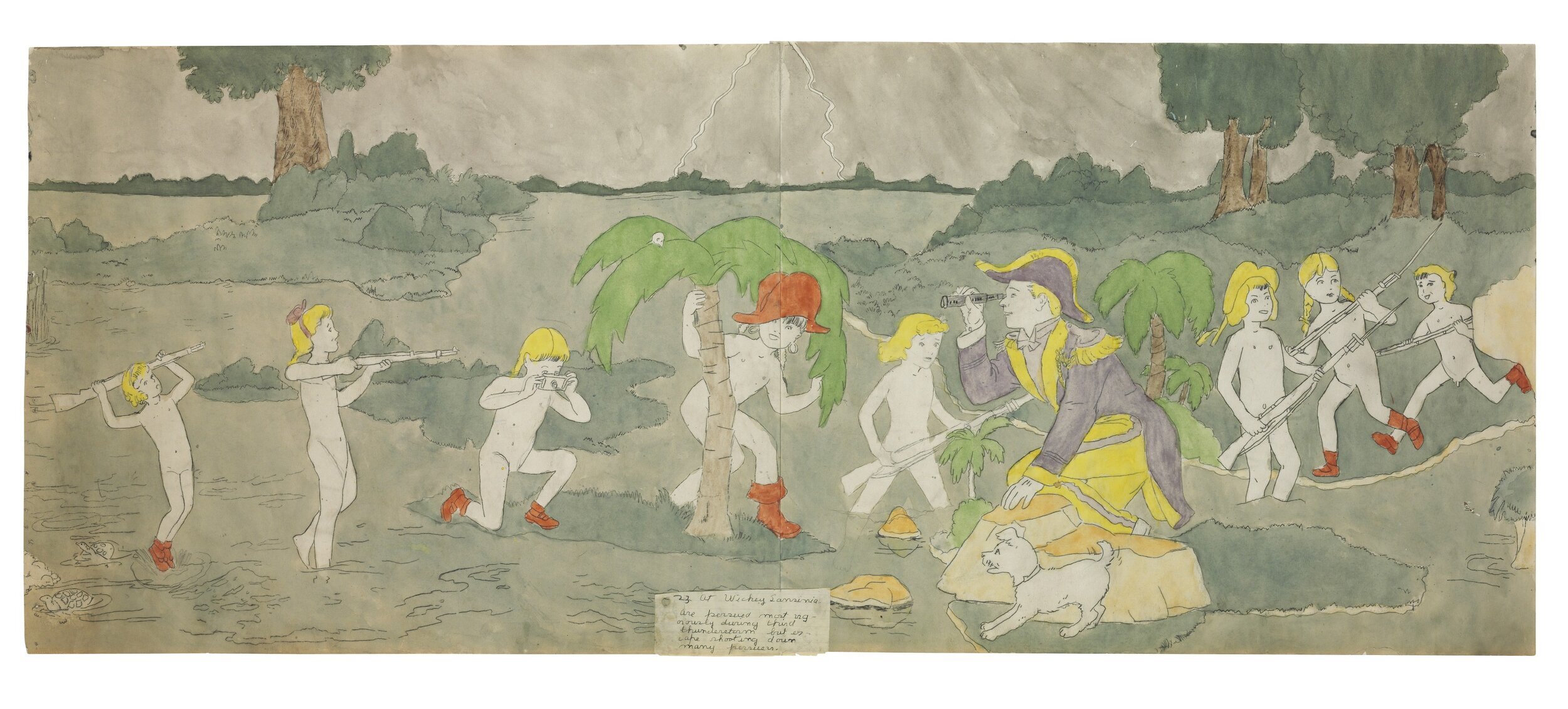

Henry Darger (1892-1973) At Wickey Sansiniacirca are persued most vigorously during thrid thunderstorm but escape shooting down many persuers,_ watercolor, graphite, ink, and carbon transfer on pieced paper,

8. Would you say you had a favourite artist or piece of work within your collection? And why?

My family was gifted a mid-sized Darger work and we lived with it for about fifteen years, but because we became financially strapped when I lost my newspaper job in 2009 following the economic downturn, we sold it at a Christie’s auction in 2015. Up until then, that was my favorite work. It pictured the seven Vivian princesses with their honorary sister, Gertrude Angeline, and their guardian, Jack Ambrose Evans, all set against a flooded landscape with a palm tree. My favorite piece now is an early Lee Godie painting ("Girl in the Miror" [sic]) that I had coveted for many years, and when the owner approached me about buying it in 2008, I snatched it up. That was the last artwork I bought.

9. Is there an exhibition in this field of art that you have felt has been particularly important? And why?

Historically, the most important exhibition in this field was when The Hans Prinzhorn Collection of psychiatric art traveled from Heidelberg, Germany to various American sites, including The David and Alfred Smart Gallery at the University of Chicago in 1985. This was an unprecedented event since the artists in the Prinzhorn Collection served as the core group from which Jean Dubuffet formulated his ideas regarding art brut. The Corcoran Gallery of Art’s Black Folk Art in America, 1930-1980 was also a milestone in the field. But the most important exhibition to me personally was Henry Darger: The Unreality of Being, organized by Stephen Prokopoff at the University of Iowa in 1996. Although it did not include some of the artist’s more graphically violent works, it was otherwise the most comprehensive traveling exhibition of Darger’s work to date.

Lee Godie, _An Actor_. (_James Dean_ crossed out on the verso), mixed mediums on board, 19 1_2 x 14 3_4 inches, n.d

10. Are there any people within this field that you feel have been particularly important to pave the way for where the field is at now?

Jean Dubuffet, obviously, since he coalesced a group of disparate mentally ill geniuses, mediumistic practitioners and eccentric rebel artists into a strong united front under the art brut banner in 1945. British historian Roger Cardinal was indispensable in broadening and humanizing the field of art brut under a new term called “outsider art” for English-speaking aficionados in 1972. Historian John MacGregor’s brilliant Darger scholarship was essential and groundbreaking, though I disagree with his otherwise over-pathologizing approach.

11. A conflicted term at present, but can you tell us about your opinion of the term outsider art, how you feel about it and if there are any other words that you think we should be using instead?

Despite being the preferred term from the mid-1970s through the 1990s, it has had a rather unhappy history since then. In the 1980s, gallery dealers began applying the label “outsider” irresponsibly and erroneously to any form of self-taught or folk art that they put on the market, thus confusing its already rather complex definition in the minds of anyone who did not know better. When African American vernacular art entered into the outsider field, some began to view the term as pejorative, saying that it discriminated against those artists so labeled because it implied that their work was somehow of less intrinsic value than that of insider artists — or because it was an example of how the powerful impose their own biased category on people they deem “outside” (meaning “other”). With all its failings, however, no one has come up with a better term. Politically correct terms like “self-taught,” “non-mainstream,” and most recently “outlier,” just don’t have the same panache as “outsider art,” so the label may remain with us for a while yet. I’ve always liked the term “intuitive art,” but most of the time I am prone to revert back to the original “art brut” moniker when warranted.

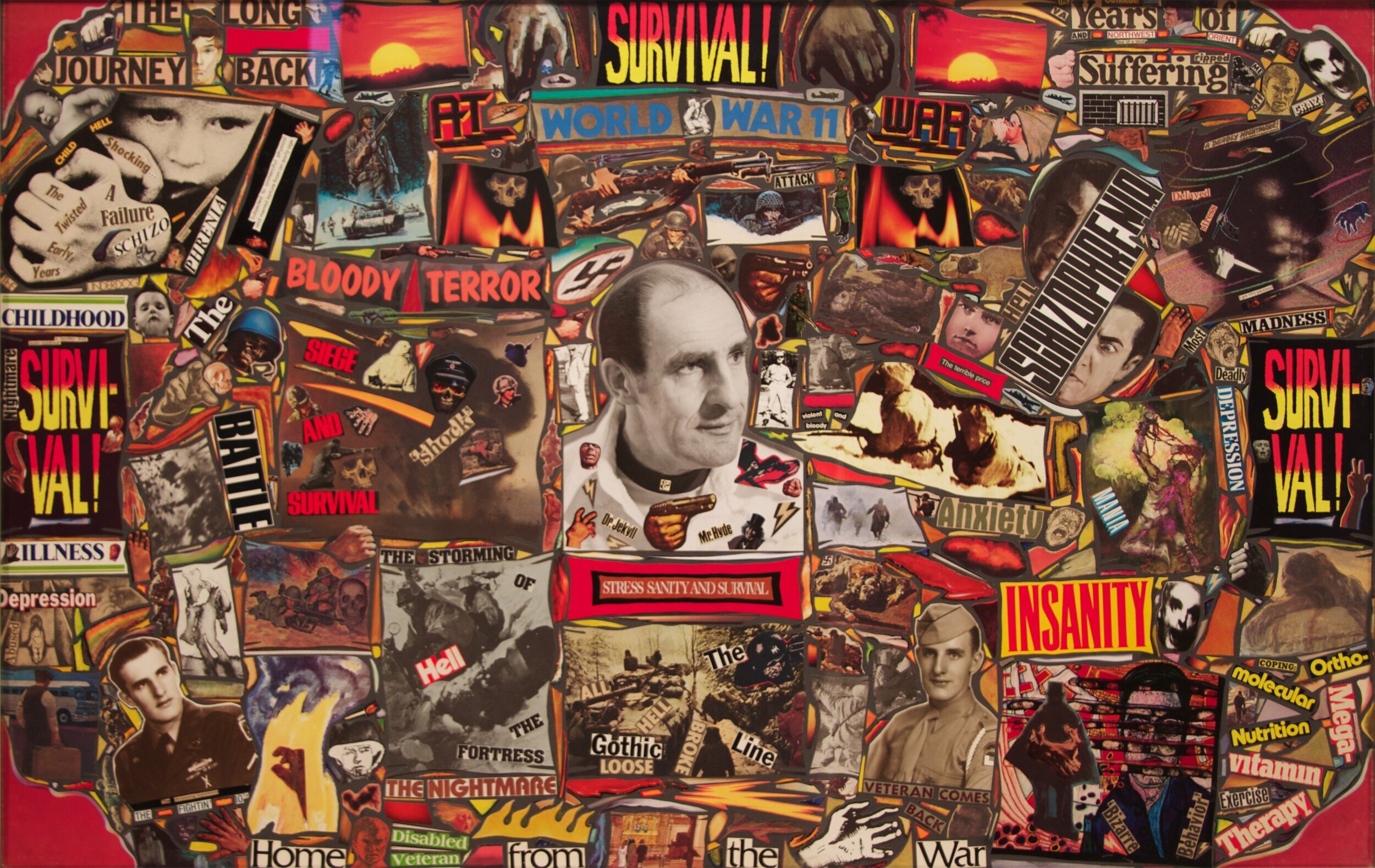

Richard Saholt, Untitled (Stress, Sanity and Survival), collage on cardboard, 44 x 28 inches, late 20th-early 21st century

12. What’s next for you?

I hope to see the publication of my “abridgment” of Darger’s magnum opus, The Story of the Vivian Girls in the Realms of the Unreal. I’ve been working on it off and on for more than a decade and just recently finished. I believe it will be useful to scholars and others interested in the meaning behind Darger’s visual art and who don’t have the time or inclination to wade through, as I have, digitized versions of the original 15,000-page manuscript in its entirety.

13. Is there anything else that you would like to add?

Not really, except to thank you for this invitation to talk about Henry Darger and art brut, which is always a pleasure.