Anthony Petullo – MEET THE COLLECTOR Series, Part Sixty Four

Anthony Petullo, now living in Wisconsin, makes up part sixty-four of my Meet the Collector series. I have seen much about Anthony’s collection of self-taught and outsider art over on Instagram, and thorugh his very thorough website. It was a pleasure to be able to talk on the phone to Anthony further, learn all about his travels to the UK to meet and research self-taught artists here, and to know how well looked after much of his collection is at the Milwaukee Art Galley now. Read on to learn more from this fascinating man …

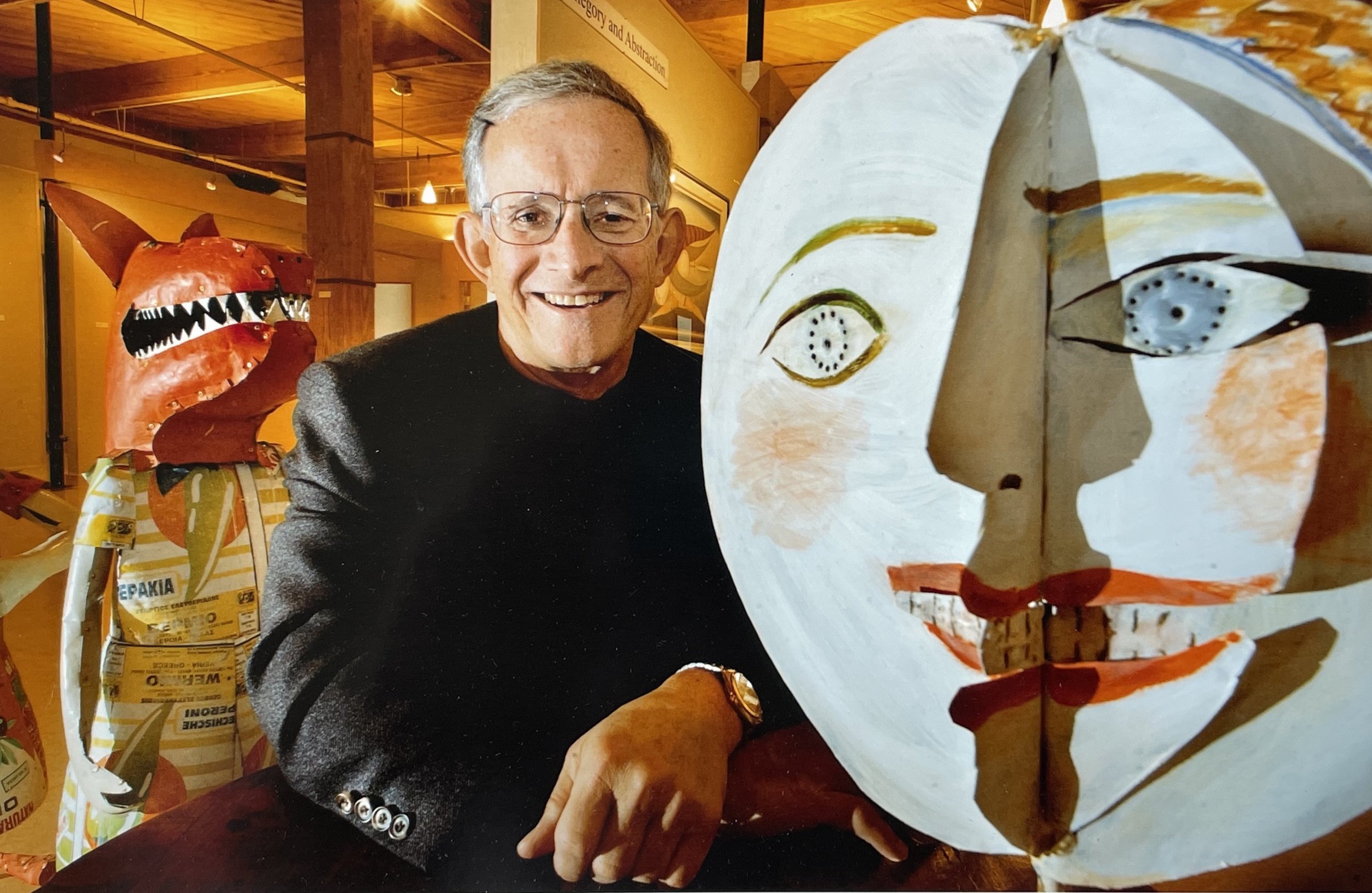

Anthony Petullo in his teaching gallery, ca. 2005, with sculptures by British artist Lucy Casson (left) French artist Gerard Rigot (right)

Jennifer: Can you tell me a bit about your background, because it seems quite fruitful?

Tony: I'm a Chicago native, now living in Wisconsin. I grew up in and around Chicago. I have a business degree from the University of Illinois in Champaign Urbana. Following graduation, I worked for Mobil Corporation for one year and then enlisted in the Navy and served three years as an officer. I then returned to Mobil for another four years. After my corporate experience, I founded a staffing company which I sold 30 years later. I opened a teaching gallery in year 2000, where I and a curator created four exhibitions a year from the Anthony Petullo Collection of Self-Taught and Outsider Collection. We hosted visiting groups, high school and college art classes and gave talks on the Collection. We also allowed non-profit organizations to use the gallery for fundraising, at which my curator and I would give talks about the Collection.

I never sold any artwork from my collection or any other art at the gallery. And there was no charge for any groups or when we opened on Milwaukee gallery nights. It was a very fun and fulfilling ten-year run. I closed the gallery when I donated 300 artworks to the Milwaukee Art Museum, much of which was exhibited in a six-week exhibition at the Museum. But I still have enough art left for two houses, and quite a bit more in storage.

Art dealer and good friend Alex Gerrard at his gallery in Battle, East Sussex, U.K., ca. 1992

Jennifer: So you called yourself a teaching gallery. So you were just like a gallery that showed works, but never sold anything, but you were keen to educate people about the works in your collection. Is that right?

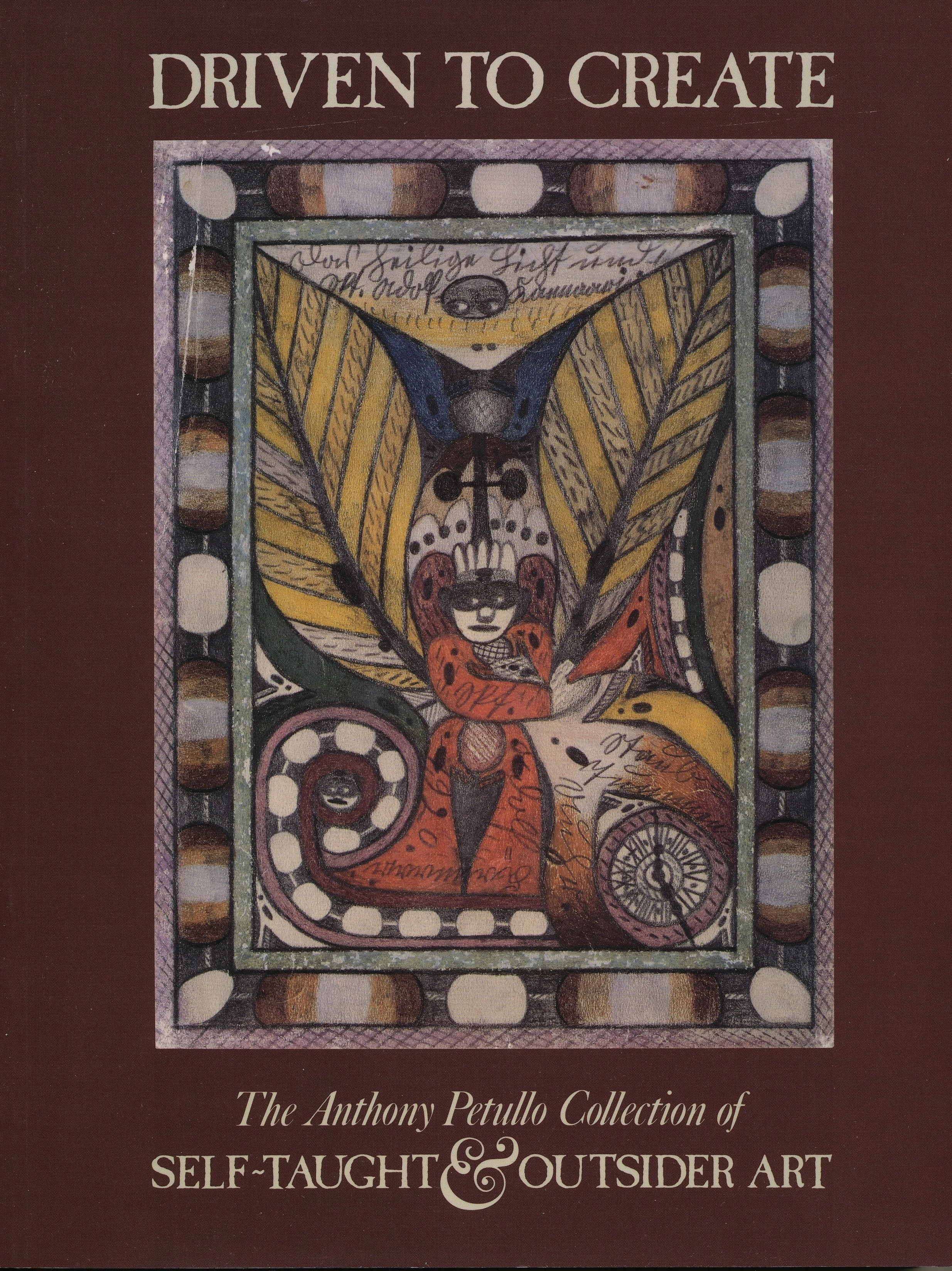

Tony: Exactly. Just like a commercial art gallery, but we made no money. In fact, it cost me quite a bit of money for ten years. But the experience was worth it. And we provided the art community with continued exposure to self-taught art, as well as writing a couple of books, something I and my curator had never done. The first book, which was co-authored by me and my curator Katherine Murrell, then an art history graduate student, was Scottie Wilson: Peddler Turned Painter. It is now the definitive book on the life and art of Scottish artist Scottie Wilson. We did extensive research for the book. Katherine went to Toronto to research where Scottie had discovered his talent and was promoted by a Toronto art dealer, after Scottie had traveled across Canada selling, but mostly charging people to see his work. I went to London and Edinburgh to research at the Tate, the V & A, the Family Records Center, and even the British Telecom, where I found that he never had a telephone number, anywhere. He used to live in boarding houses and he’d use the “common phone in the hall.” Frugal, to say the least. Then I visited the Edinburgh Museum which has the bulk of Scottie Wilson personal effects and archives. While in London, I even hired a taxi, who the doorman at the Savoy recommended, to drive me around to find places where Scottie Wilson had lived, had his stall, and even a very small, difficult find, synagogue. At the end of the day, I asked the driver how much I owed him and he said, “nothing, it’s been a very enjoyable day.” I mentioned him by name in the acknowledgment section of Scottie Wilson: Peddler Turned Painter.

Jennifer: Did you ever meet Scottie in person?

Tony: No, I didn’t. A friend of mine, Bill Hopkins (now deceased), was a journalist in London. Bill knew Scottie Wilson and was a mentor of sorts. When WWII ended, Scottie left Toronto for London, much to the disappointment of his dealer who had exhibitions planned for Scottie. In London, he began hawking his work to art dealers. One dealer was very interested in his work and would have put him in the upcoming exhibition with Miro, Dubuffet, Picasso and others, but the announcement and catalogue had been completed. So he decided to put some of Scottie’s works in a back galley. Visitors seeing his work assumed he was among the front galley artists’ group. Several years later, Jean Dubuffet wrote to Scottie in London and asked that he come to his Paris home and bring a portfolio of his work. Scottie wasn’t too keen on the idea, but showed Dubuffet’s letter to Bill Hopkins who persuaded him to go, and Bill would come along. When they arrived at Dubuffet’s house, they were greeted by both Dubuffet and Picasso. The two famous artists began haggling over Scottie’s drawings. I have seen Scottie’s drawings in a very extensive exhibition of Dubuffet’s work and his many collections.

Jennifer: Wow, I'm just going through all of Roger Cardinal’s things now with his wife, and just last week, I found all the letters where he's corresponded with Scottie Wilson over the years and many interviews he's done with him, or others that had. I haven't fully looked through it yet, but it looks absolutely fascinating because Roger just kept every single conversation they had.

Tony: That’s not surprising. Roger was a very thorough art historian. When my collection went on tour, curated by the Milwaukee Art Museum director Russell Bowman, it was exhibited in six art museums over a two-year period. Roger Cardinal agreed to write an essay for the catalogue that accompanied the Collection. He once told me that I was his favorite American collector because I was rather unorthodox. I was happy to be among his many, many friends and admirers. Roger said the Petullo collection is not an encyclopedic collection, it consists of only which Petullo likes. He was an interesting man, entertaining, joyful, and happy to share his knowledge.

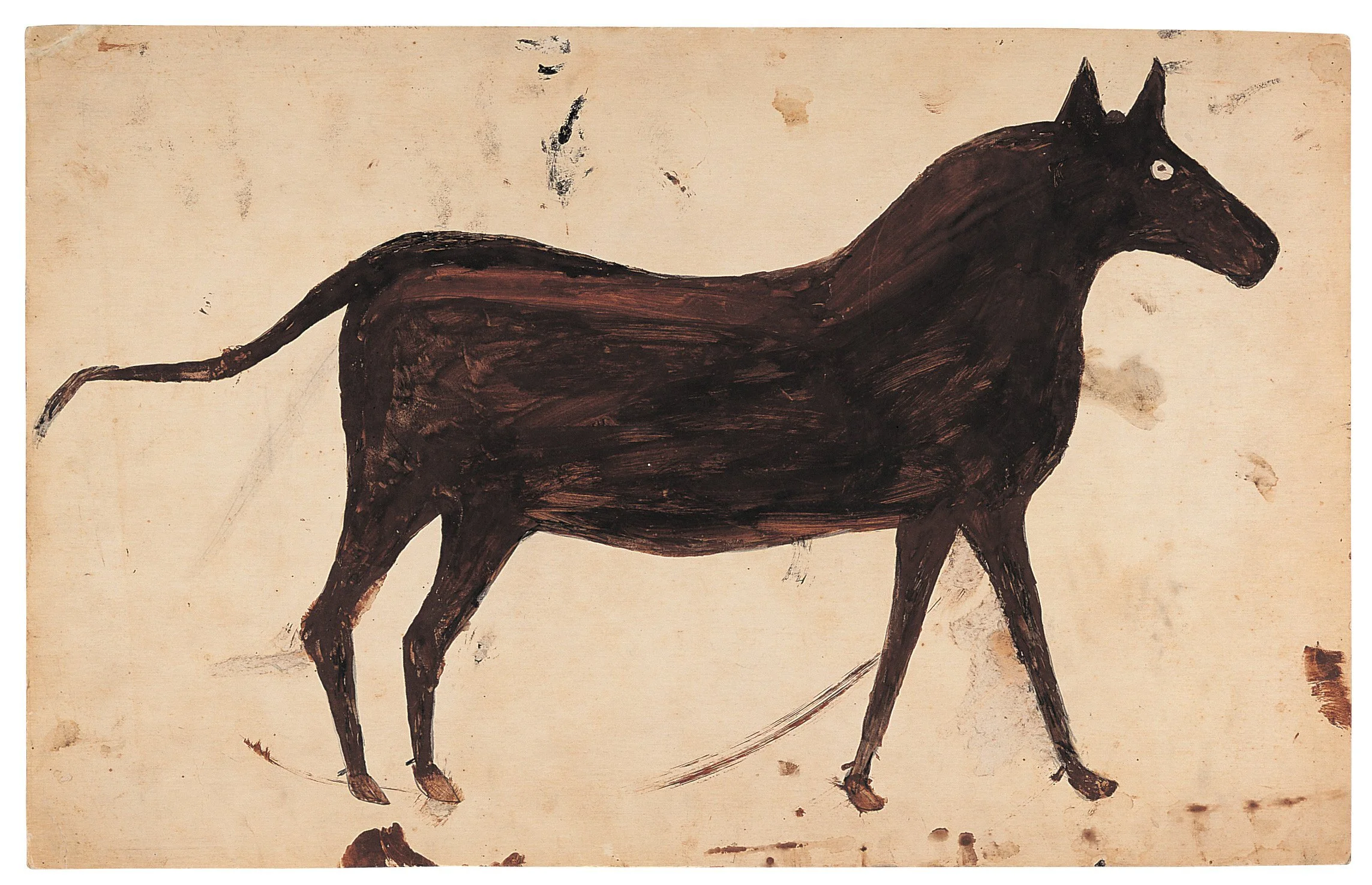

Bill Traylor’s Brown Mule

Jennifer: Yeah, he was lovely. So, I've read this on your website, but when did your interest in this field of outsider, self-taught, folk art begin?

Tony: I was a volunteer at the Milwaukee Art Museum Lakefront Festival of the Arts, eventually becoming president of the Friends of Art. I got to know many of the artists, curators, dealers, and media. I began collecting a variety of inexpensive prints, drawings and watercolors, but was particularly drawn to the self-taught. On a trip to the UK I purchased a print by English printmaker Graham Clarke, and then many more of his prints. Through Graham, I met Alex Gerrard, who at the time was Graham’s publisher. Alex also had a small gallery in Battle, just up the road from Hastings, and we soon became fast friends. Alex introduced me to the work of many European self-taught artists and he became my principal UK and European dealer. At the time, few Americans were collecting European self-taught artists, so I got in early, before the prices really escalated.

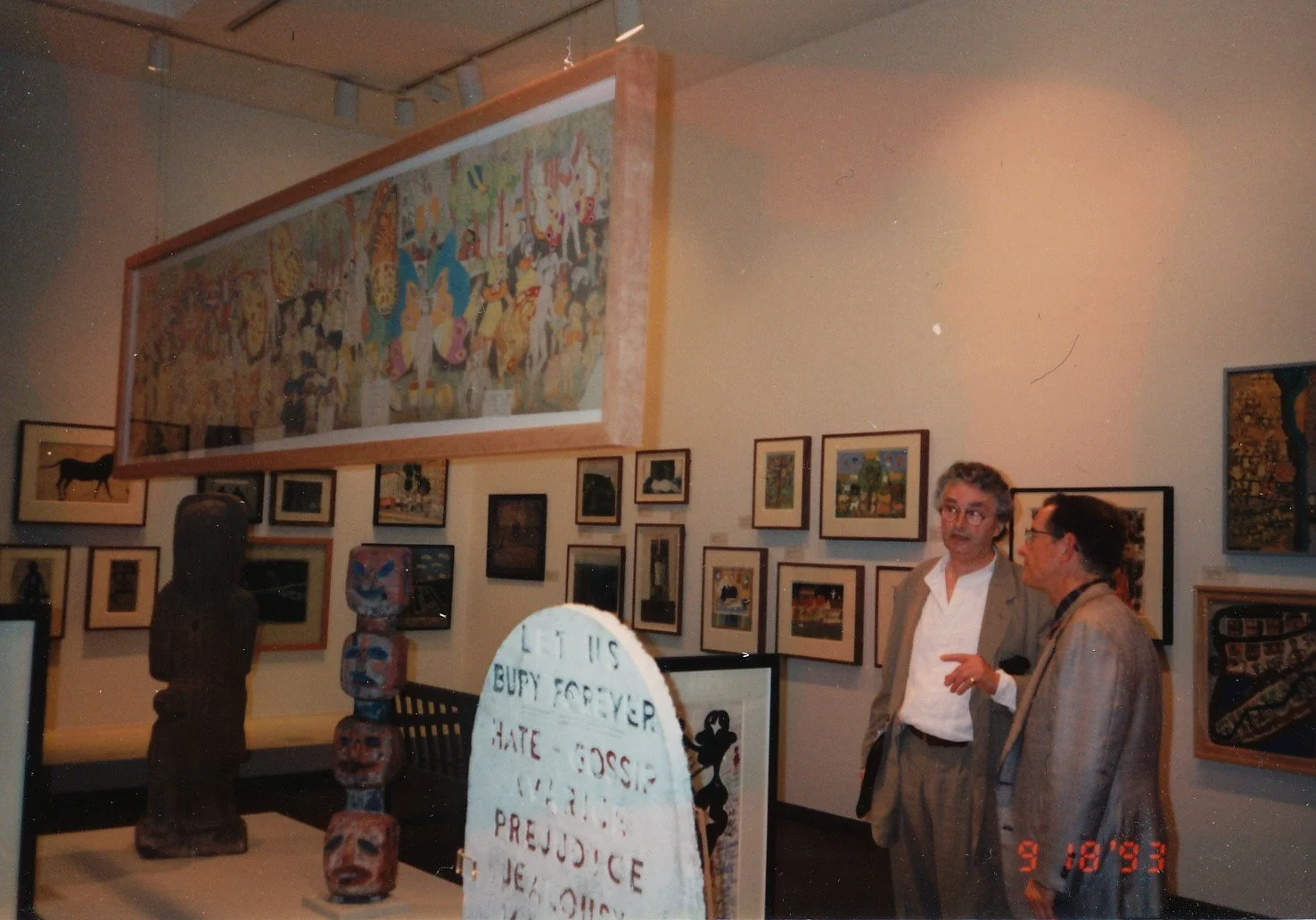

In January 1990, Alex called me to say that he was holding a catalogue of a Sotheby's sale to be held in New York City, and on the cover was Brown Mule – a work by Bill Traylor, born into slavery in Alabama. He suggested I buy it, which I did. I had to place a blind bid because I couldn't be NYC, and I couldn't be on the telephone. But I did win it. Alex called me later in the month and said, I have found an Alfred Wallis, the Cornish self-taught naive artist. And you know, they don't come up very often because most are in university or museum collections, or private collections. Traylor and Wallis became the anchors of my collection. In about three and a half years I collected more than 150 self-taught works that I would judge as museum quality. I kept showing them to everyone including the Director of the Milwaukee Art Museum, and he suggested, well, you have to have this artist and this artist, to which I said, I'm just going to collect what I want. By the fall of 1993, we opened a 95-piece exhibition at the Museum of American Folk Art. It was the first time that the museum had ever shown Europeans, and the first time they had ever shown outsiders.

Jennifer: So am I right in thinking they were more showing folk art objects then?

Tony: Yes, essentially American folk artists. In fact, the museum was called the the Museum of American Folk Art. To properly reflect what they now collect and exhibit, the museum is now the American Folk Art Museum. Several NYC art dealers came to the opening of the collection and were very happy because the museum was exhibiting what they were selling. The New York Times wrote a favorable review of the exhibition. That was a very good start.

Jennifer: Did they contact you about doing that show? Or did you contact them?

Tony: The Milwaukee Art Museum had already confirmed museums in Tampa, Florida; Akron, Ohio; Milwaukee, and the Krannert at the University of Illinois, but we were hoping to commence the tour in NYC – so the Folk Art Museum was the logical place to start. After much hesitation, the Folk Art Museum finally said OK we’ll take it. That was June of 1993. We had only three months to prepare the art and publish a catalogue before the September opening. The Milwaukee Art Museum art preparators and registrar staff descended on my corporate offices and my home and removed 95 artworks. The collection and a supply of the catalogues were delivered with time to spare for the six week run at the Museum of American Folk Art. After the NYC exhibition and good reviews, the Little Rock, AK, Museum asked to join the tour, which we accepted. The tour was then six stops. A few years later, the collection was exhibited at the Kohler Art Museum and the Intuit Center of Intuitive and Outsider Art in Chicago. I presented a talk at each of the eight museums.

Anthony outside Alfred Wallis’ house in St Ives, UK

Jennifer: And for you, why is it important that you have shows from your collection?

Tony: Most collectors are probably proud of what they've collected. And I just thought it would it be wonderful to share my collection with the public. Besides, early in my collecting I had decided the majority of the collection would be donated to museums. And I had the teaching gallery, so that more people could appreciate the collection. In fact, we would participate in the arts district gallery nights. Our gallery exhibitions were very well attended. Many visitors became regulars because we kept changing the “thematic” exhibitions. One exhibition was titled, “A British Invasion.”

I thought it would be better if we allowed the public to see the collection. That's why I gave 300 works to the Milwaukee Art Museum, so that they could then exhibit a portion of it at all times. There’s also no way I could maintain over 600 works if I didn't have that gallery or give some to the museum. It's been great fun. Later in 2022 there will be a small exhibition of 30–35 artworks of the “The Collector’s Favorites.”

Jennifer: So when you gave it to them, did you stipulate that they'd have to have some works on show from your collection at all times?

Tony: Yes. Milwaukee Art Museum is obligated by contract to have a certain percentage of the collection on view in the Museum’s Petullo Gallery at all times.

Jennifer: And when did the gallery room get set up that is named after you?

Tony: A few years later after the Museum renovated the permanent galleries. There are other self-taught artworks not from my collection in the Petullo Gallery that the Museum has collected in prior years.

Jennifer: And this teaching gallery that you had, what years was that open?

Tony: From 2000 until 2010.

Jennifer: And did you close that gallery because pieces from your collection went off to Milwaukee and other places?

Tony: Yes, the museum was preparing works for the exhibit to begin in 2012. The show was on for six weeks in beginning of January 2012. And I'm told something like 65,000 people toured the exhibition. I’ve been a trustee of the Milwaukee Art Museum for 25 years. Our primary exhibition gallery was large enough to exhibit much of the 300 artworks I gave to the Museum. It was quite popular, having had a considerable publicity because I was a local collector. On the two two opening nights I gave a talk featuring photos I took of the staff preparing the exhibition. To my knowledge, no-one has ever done that at our museum. When visitors come to see any exhibition, only people who have worked or volunteered at a museum have any idea how much prep work goes into an exhibition, from conservation, reframing, wall texts, curatorial layout with the designer, and all the art handlers doing the installation. Somewhat like all the people behind making movie. I just thought it would be nice to highlight the staff.

My website, as you probably noticed, has sections on how to start collecting, how to care for your collection, because I have had so many questions about those topics at the various venues where I have spoken.

The living room of Anthony’s home in Wisconsin with artwork by artists from ten European countries and the U.K.

Jennifer: And if we come back to your website, it's quite rare for a collector, from what I've seen, to have a website. Is it just because so many people were asking you these questions all the time that it just made sense to kind of keep it all in one place?

Tony: Thank you for that. Because I knew that I would be one of the few collectors who has a website. It’s because I have this desire to share. But also I wanted to preserve what I built. Early on in my collecting I had decided that most of what I collect was going to go to museums. So while I collected, I always had that thought in mind. When I would go to a gallery or to the Outsider Art Fair in New York, I would ask myself if the artwork I was considering was going to fit in the collection. What’s also important, if you're going appreciate the work of an artist, you should see more than one or two works. My collection has depth: Scottie Wilson for example, I think I had close to 25 images. Works by James Lloyd’s are in the teens, Albert Loudon in the teens, Sylvia Levine in the teens. These are all British artists and there were lots of others where I had multiples. Most people now can't afford multiples of Darger or Ramirez. I bought my Ramirez and Darger from the original collectors. I wouldn’t buy either one of them at the current price. I can afford it, but I don’t want to spend that kind of money on one piece of art. Besides, I’m a “reformed” collector. My wife and I still buy eclectically, but nothing of great value.

Jennifer: Well, yes they are a lot of money now.

Tony: You know, my Brown Mule by Bill Taylor is large. Today I'm sure it would be at least 10 times what I paid, probably more and the Darger, maybe 20 times more than what I paid for it.

Jennifer: Are these ones that you have kept in your home or have you given like the big named pieces to the Milwaukee Art Museum?

Tony: You'll see on my website, underneath each artwork image – if it says Milwaukee Art Museum they own it. If it doesn’t say the Museum, I still own it. Except for the Darger and Ramirez, I kept some works from almost every artist, so I have plenty left. I probably have at least one museum quality left by each artist. I would say 150 good quality left, and a lot of other things. I'm an eclectic collector and I collect other things too. I’ve stopped collecting in this genre.

Jennifer: So the Darger and Ramirez are both in Milwaukee Art Museum then?

Tony: Yes. The Darger is double sided and 90 inches long. It's a big Darger and I bought it from Nathan Lerner, who was Darger’s landlord. I had my choice from a large number of works. The Director of the Milwaukee Art Museum went with me to make sure that we got a really good one. And then Ramirez… I bought that from Jim Nutt, who was introduced to the Ramirez work while a graduate student in California. Art dealer Phyllis Kind told me she was initially selling Ramirez drawings for a couple of hundred dollars each. It’s hard to believe.

Alex Gerrard and Anthony Petullo at exhibition Driven to Create: The Anthony Petullo Collection of Self-Taught & Outsider Art at the American Museum of Folk Art, 1993

Jennifer: Oh my god. That's laughable now. So you said that you've now stopped collecting the genre. Was there something that stopped you or had you just got to the point where you were like, I'm quite satisfied that I've got everything that I want?

Tony: Yes, satisfied is a good word. Also, much of what I would buy would go into storage. I’ve run out of wall and floor space. I’ve never sold a piece and I've never traded a work. That was not the purpose of my collecting. The purpose was that I was going to give it away eventually. Like a big game of “show and tell.” Or that I would keep some as they make me happy. Which they have. Monica Kinley gave me a couple of works, as did Michel Nedjar and Albert Louden. They knew that most of my collection would eventually end up in a museum.

I mean, if you look at English artist James Lloyd, I’m always amazed at his pointillism. I sometimes look at his works and wonder what if he had never been discovered. What a great loss to the art world. He had been discovered by an art critic who had a summer home near where Lloyd lived. Lloyd’s wife contacted the critic and he and a friend visited.They were so fascinated that they arranged for a gallery show in London. The BBC eventually interviewed him, and they talked about how much his artwork looked like that of Rousseau. The BBC had him wear a beret like Rousseau, when he was on their telecast. However, if you asked people in the UK, even art dealers, if they have heard of James Lloyd, almost all never have.

Jennifer: I certainly haven’t, so I’ll look him up now.

Tony: And if you have my book Art Without Category, you can see the pointillism up close, and on my website as well. It’s remarkable. The Portal Gallery in London, now closed, was rather small, but they had the most number of James Lloyd works for sale.

Jennifer: Well because you live in America, what is your fascination with European art? Is it because, like you said, lots of people in America weren't collecting it?

Tony: I found so many self-taught artists in London and around the UK that I very much liked. More than I found in the US. Perhaps it was the naive style, which is less popular in the US. But it was my connection first to the East Sussex printmaker Graham Clarke. He was a fantastic printmaker of historical scenes. He made copper etchings on handmade paper, which were then hand colored. Most of his output was sold in Japan and Germany, where they would be sold for two or three times the price in the UK. I brought him to the United States to lecture at the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design. He spoke with faculty and the students about printmaking and running a business as an artist, which is rare, very rare. The business side is usually not uppermost in an artist’s mind. I bought my first Clarke in a gallery in Broadway, in the Cotswolds, in 1976. Later I called the gallery and asked how I could get more. The gallery said they couldn’t get anymore, as all his prints are being exported. So I said well, who's the publisher? And they said a fellow named Alex Gerrard. So I called Alex and on my next trip to England, I met with Alex and sure enough became good friends and off we went.

I’ve never studied art, not even an art appreciation course. I am just like my artists. I'm self-taught.

A wall of works by artists from the Gugging and others

Jennifer: And coming back to another point, you said earlier that you've never done any swaps and you've never sold any artwork. And I know when I speak to other collectors, they often do swaps. Is there something that stops you doing that?

Tony: Why would I do that? I spent considerable time selecting what I liked and I still like them. I built it as a collection and I wanted to keep it as a collection. So why would I sell? If I wanted to sell something today, I could make a lot of money, but why? I'm a philanthropist, and I support many non-profit organizations and one university. It just didn't seem right. The worst thing that can happen to a “collection” is to sell it at auction. That’s like building or refurbishing your favorite classic car and then selling. What’s the point? Terrible. When I lecture I say, you know the way to build a collection is not letting other people to tell you what to buy. You build it because it's very personal. Once you get some basic knowledge on what is apparently good, not good, you start buying only what you like. Really great collections are the work of one person. You can get advice here and there, that's fine, which I did from artists, art dealers and academics, and Roger Cardinal, but it didn’t have significant influence on my basic instincts. The great outsiders and the authentic self-taught artists are not influenced by anyone. All you have to do is look at the group and how all these artists are so different. Not one of them is like another.

Jennifer: I know quite a few collectors that are quite influenced by art dealers in America around the stuff that they buy and very much rely on the art dealer to kind of say, oh, you know, this is a good piece of art, you should buy it, as opposed to them personally thinking, oh, that's a good piece of work.

Tony: You're absolutely right. How could those “art acquirers” say they personally selected all their art? How can they show their art to others and explain how and why they bought it? As I’ve said, a great art collection is very personal and built by one person. The dealer has the inventory, but a discerning collector buys only what they like from the dealer or not at all. When I went to the Outsider Art Fair… I used to go every year in New York. I would go on the opening night, but I would make sure to get to the front of the line when the door opened. And I would rush through the entire show. Most dealers knew me. And I would quickly look at the art in their booth and if I saw one or more things I liked, I said, “red dot”, which means I just bought it. You have to have mutual trust to do that. When I returned to the dealers where I had indicated “red dot”, they frequently would say, I could have sold this one once or twice since you left. It was not uncommon for me to buy 10-15 pieces at a time, and they just shipped them. I usually didn't even have to pay. They just shipped them with an invoice. Wow. It was like a business. They knew it was a business with me.

One of the things I never did was buy directly from an artist who was part of a dealers stable of artists. I bought from some artists because they didn't have a dealer or they had abandoned their dealer. There is trust there. I became known as a guy who really knew what he wanted. Instinct told me what to buy. Once I trusted my judgement, which took a while, I made fewer mistakes. In starting a collection you’re going to make some mistakes. And a lot of those that no longer work for me, my children have, and they love them.

Jennifer: You’ve said there are some pieces that you don’t hang, why is that?

Tony: Yes, there are some pieces I don’t usually have on view. But they would be very well situated in a museum. I like them, but they aren’t the most suitable for a happy environment. I like to be surrounded by work that we really enjoy. I'm a happy person, so there are certain works that I just can’t have up on a regular basis.

Jennifer: Would you say that you've got a favourite piece, like if your house was burning down? What piece would you think oh my God, I need to grab that before I leave?

Tony: I was asked that question recently. I would go around and grab as many important small works as I could possibly get, and walk out. The first thing I would grab, well I've got a shelf that's got Alfred Wallis on it, and I’d take that and some other works on that shelf – like four or five works. I would grab as many as I could, take them in a bag or something.

Jennifer: So you don't have one particular favourite, you would just try and grab as many as you could?

Tony: Yes, it's like asking which is your favorite child? I have four and they’re all favorites for one reason or another.

Paintings by Dora Holzhandler, British, (b. France), table by Gerard Rigot, France, and above a painting by Syvette David, British, (b. France)

Jennifer: And would you say of all the exhibitions that you've seen over the years, is there one that you think has been particularly good for kind of showcasing this field of art other than your own? Lots of collectors say that the Black Folk Art Show, which I think was like 1982 or something, was the show that they thought was like a really seminal show for this field.

Tony: Oh, I think that was Edmondson, right? I think Bill Taylor was in the exhibition too. Yes, that was good, but I never saw that show. I hadn't started collecting seriously at that point. You can see that from my website. Oh back to the website. The reason I put that together was that I wrote everything that needed to be written in there. I created the website for three audiences. First of all, there's the curious and those who want to learn more about art. Secondly, there is the collector who may collect in this genre, or may collect anything. And there’s collectors asking where did you get all this stuff? And the third is the scholar. The site has a brief history of the genre, and links to other important resources. There were a couple of scholars in in the UK who wrote to me that my book Scottie Wilson: Peddler Turned Painter was very well done and much needed. I had never done any serious writing and neither had my curator, a graduate art history student. I even started a publishing company to publish the my books. I also published one for the Milwaukee Art Museum on all the artwork the Museum’s Friends of Art had financed. It just shows that if you do it the right way, and thoroughly, it will be appreciated. That's one of the reasons I created my website. It’s a historical record of an art collection and the collector. It's more than just showing nice pictures.

Jennifer: I’ll look it up. So if we're looking at people, do you think there's any people within this field that you think have been particularly important for raising awareness of it?

Tony: You'd have to include John and Maggie Maizels. They continue to broaden the self-taught world, highlight new artists, and write feature stories on the “great ones.” They’re wonderful promoters of the genre. Certainly, among the academics, Roger Cardinal is at the very top. If you go back further – Jean Dubuffet, artist, collector, promoter – would be a standout. His definition of Outsider Art is still valid, at least for those who were in institutions and those he placed in his so called “annex,” such as Madge Gill, Scottie Wilson, Albert Louden and more.

Jennifer: You said that you've stopped collecting this work, so what sort of work do you collect now?

Tony: Well, when my wife and I visit juried fairs someplace, we might buy this little thing or that little thing. So, nothing serious, and certainly nothing like some of the giants now in our collection.

Jennifer: What’s a juried art fair – do we have those in the UK?

Tony: My art exposure began in 1973 as a volunteer at the Milwaukee Art Museum’s Lakefront Festival of Art. In its almost seventy year existence, there are usually about 180 artists from all over the United States. But someone had to screen them first. So, three or more academics and/or respected top notch artists are part of a jury. Today works are submitted digitally, originally submitted as slides, so the jury reviews all the submissions and selects the artists to be included. The artists include those working in all mediums – fabric, painting, drawing, ceramics, wood, glass, jewellery, etc. It's still the same today. There’s often a big volunteer committee that puts the fair together, working several months in advance. Then on the first day of the fair, another jury visits each of the artists’ booths and selects awardees for cash prizes and ribbons, so buyers can see who won awards. A very nice perk for the winners.

So, on my website, I tell people a juried fair is a good place to start your search for art. There they find a large group of accomplished artists who have been pre-screened. The choices are up to you. Talk to the artists about their art, they love to talk about the their passion.

Anthony in his home with two Lucy Casson sculptures and a Mona Lagerholm, Sweden, on the left

Jennifer: And then my final question is, and I know you write about this on your website, what do you think of the term outsider art and do you like to use it?

Tony: I mentioned that in the foreword of my book, Art Without Category, that it's still a dilemma for the genre. There are varying degrees of self-taught, from the neighborhood artist at a street fair who paints pretty pictures – to the creative genius in a mental hospital. Picture the types of self-taught artists on a linear scale, with the neighborhood painter on the far left side. Those artists may simply be working in a naive style because it’s cute and sentimental and doesn’t require trained art talent. Or they may be more accomplished but may (1) imitate other artists, (2) learn from other artists, and (3) on request, will reproduce a work they have already done. A “genuine” self-taught or outsider artist would do none of that.

Then in the middle of the linear scale there are those that create in two or three dimensions, who are just doing their own thing. Uninfluenced by anyone else. Typical American folk art painters like Bill Traylor, born into slavery in Alabama, or naive Cornish painter Alfred Wallis, a retired mariner. Two older, widowed, poor men drawing and painting experiences and observations from their lives with crude materials, just to pass the time. But so ingenious and innovative that many decades later their artwork is selling at unheard of prices, rather than for a few dollars or shillings. And their artwork today is considered contemporary, hanging in art museums along with the contemporary super stars of their era. With no mention of being self-taught.

Next comes the visionaries like Scottie Wilson and spiritualists like Madge Gill, who create driven by visions they perceive, or a spirit that guides them. They are totally unaffected by society or other artists. They may not even have any interest in other artists. Finally, on the far right, are the Outsiders: Dubuffet said, “they are outside the cultured art world and outside of mainstream of society, creating artwork in which there is no mimicry.” I subscribe to that definition of Outsider. The artists of the House of Artists in Gugging in Austria is a perfect example. Others would be Ramirez and Darger.

On one occasion I took Albert Louden to lunch in London. During lunch I asked Albert if someone asked you make another painting just like one you had done before, could you do it? He just looked at me like he didn’t know what to say. I don’t think he would or even could do it. For Scottie Wilson, almost everything Scottie did was a vision and he had to get it down quickly, so he didn't lose that vision. So yes, I think the best thing is just keep calling it self-taught art.

Jennifer: Well, yeah. It's a shame because I think in England, still to this day, lots of these artists are overlooked. And I think this whole field in general is overlooked I think, because a lot of people still don't know about it. It's kind of often dismissed and there's these big shows that come in and then disappear and then there's like nothing around for a while again.

Tony: Yes, I wrote a few books and created a website specifically to preserve the history of the artists I collected. The vast majority of art in early American history, specifically early nineteenth century, was made by self-taught artists. Utilitarian objects like retail signs, canes, weathervanes and even portraits were done by self-taught artists which, in most cases, was self evident. Budding young, and not so young, American artists traveled to France, Italy, Spain and England to work with trained painters and live in their environment. The fact that those countries have so much classical art may help explain why there is little interest in art by self-taught artists. The art world in those countries already has plenty to keep them busy. This left a wide open category for me in the UK. I had little competition for works by great self-taught artists. The UK’s loss is my gain.

Jennifer: Finally, is there anything else that you'd like to add that I haven't asked you already?

Tony: Well, yes, I'd like to compliment you on so many wonderful interviews. Thank you so much.

The catalogue Driven to Create: The Anthony Petullo Collection of Self-Taught & Outsider Art published for a six-museum tour 1993-95