Adam and Flora Hanft, New York - MEET THE COLLECTOR Series Part Fifty-Eight

Adam and Flora Hanft were suggested for my ‘Meet the Collector’ series through several other collectors. I have never met them, but I’ve read several of Adam’s written pieces for Ricco|Maresca’s blogs. It was fascinating to chat with them back in 2020, so here is our interview as part fifty-eight of my series.

Flora and Adam Hanft at Ricco|Maresca Gallery. Photo by Frank Maresca

1. When did your interests in the field of outsider/folk art begin?

Flora: A zillion years ago. We are big collectors across an undisciplined range of attractions; one of those accumulative obsessions is artists’ mannequins. A talented and pioneering dealer in this genre - who also dealt in outsider art, by chance – is Marion Harris. One definitive day, Marion had some works by Howard Finster in her booth, and we bought a few pieces. I think Finster is the first access point for many collectors. We’ve also collected folk art for a long time, and there is clearly both a connection and a distinction between them.

Adam: A lot of people get confused, because there is an untrained dimension to both. The distinction, though, is utility. A gorgeous hand-painted trade sign from a haberdashery store has utility, a clear function. Outsider Art has only expressive utility for the artist.

2. When did you become collectors of this art? How many pieces do you think are in your collection now? And do you exhibit any of it on the walls of your home or elsewhere?

F: I’d say our formal badging with the first Outsider Art Show in Manhattan. Marion offered us free tickets, and we’ll go anywhere with those in hand. Although they became the costliest free tickets of our lives.

A: When we saw the work displayed in its entirely, the visual wallop was unavoidable. Suddenly, the influence of training and the application of historical perspective made other art feel entirely self-conscious, if not manipulative, by comparison.

F: We should be better at inventorying and cataloging. But we have an Outsider approach to the conventions of collecting.

A: And besides, counting can put you dangerously close to realizing you have an addiction problem!

F: We have pieces that are hanging, while some are just hanging around, hoping for their moment.

A: We believe that wall space should not constrain one’s appetites.

F: It’s interesting to look back on the work you’ve acquired over the years; it’s kind of a living evolution of your personal taste graph. Some things grew even deeper in meaning, others provoked the “What were we thinking?” reaction. That’s not atypical. The eye grows more astute, whether you like it or not.

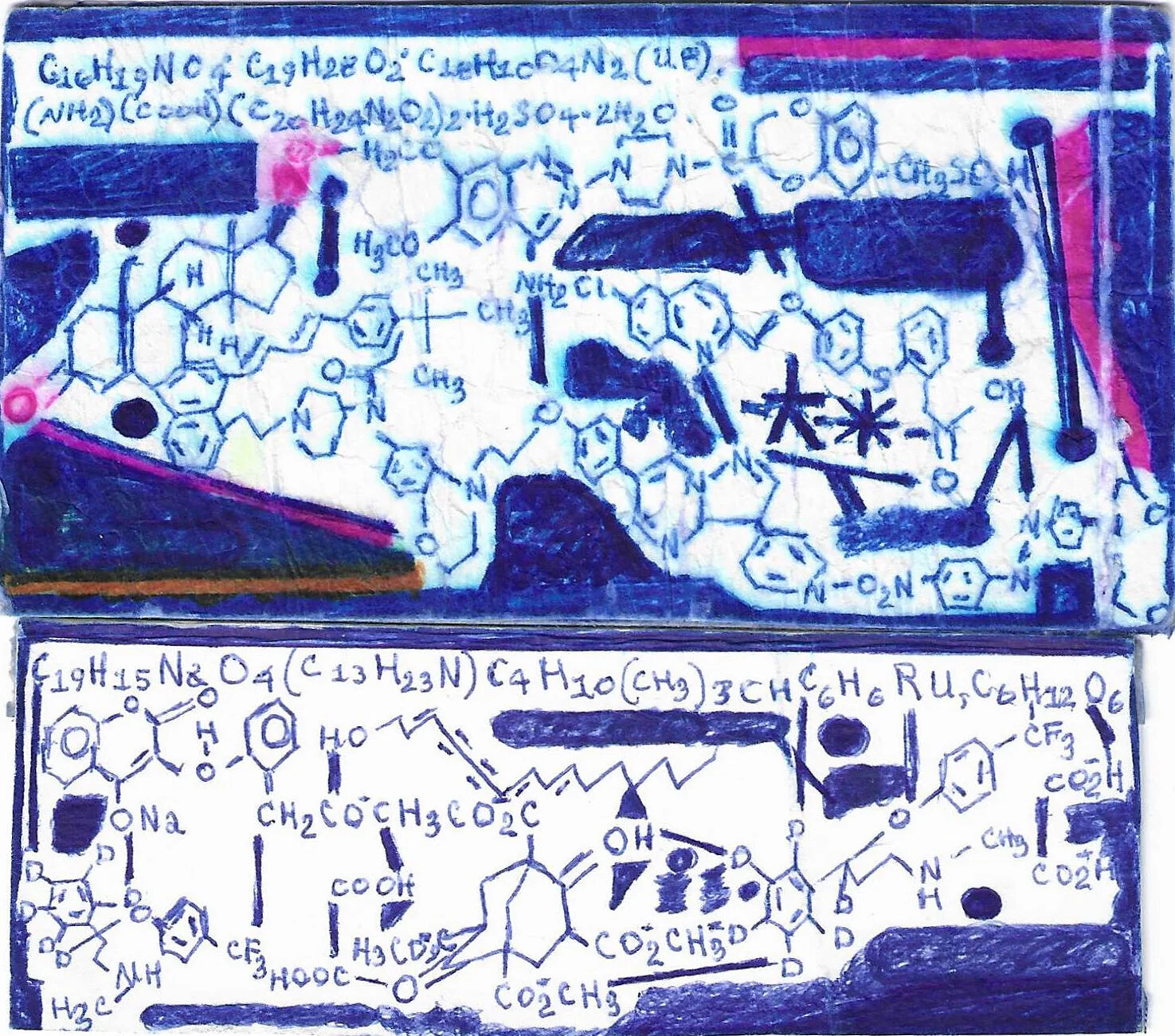

Melvin Way, NH2, 2018, Ballpoint pen on paper, 4 x 4½ inches. Courtesy Andrew Edlin Gallery

3. Can you tell us a bit about your backgrounds?

A: I worked as a comedy writer, but soon realized the human race didn’t deserve to laugh. I went into advertising as a copywriter, because I thought the human race should acquire more stuff. Eventually I started and ran a creative agency, so basically I am in the strategy, branding and messaging business. The propaganda industry. Design and visual presentation and aesthetics have always been part of what I do and what I find compelling.

F: I was an art major in college – I went to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, which means I was the opposite of untrained. But I started my career as a copywriter, worked in agencies and on the client side, and eventually set up my own business. I still love the act of writing, although I am, well, untrained.

4. I understand that you like to collect contemporary art alongside outsider/folk art - What is it that draws you to each field?

A: Our interests, I would say, are at this point 90% outsider vs contemporary. What draws us to Outsider is the sheer velocity of emotion, un-mediated by what Harold Bloom, speaking of the literary world, famously called “the anxiety of influence” in his iconic and persistent book title.

F: With Outsider, you feel like you are listening in, or should I say, “looking in” to artists in conversation with themselves.

A: And the range is so vast. We are drawn to many different kinds of material, but I will say we are most lured by works that tend to have an obsessive quality, like the mathematical savant George Widener, or disciplined yet id-driven work of Ramirez, an obvious master. They are working something out, over and over and over. They live inside their own rigor.

F: What’s so stunning is that without training, without frameworks, their visual language is so immediately recognizable and inescapable. I mean, think about Edward Deeds locked up in the institution, and we see this captured in his drawings, creating work that is monumentally distinguishable.

A: Or James Castle, locked up in himself.

F: Or the snug tightness of a Melvin Way. There’s something so powerful about Outsider artists struggling with their demons – art becomes a simultaneous escape from, and into, themselves.

A: In terms of contemporary art – and the term is so slippery because an Outsider working today is a contemporary artist – we are drawn to the same qualities. We don’t like those who play to the audience, who are too “performative”, who beg or sometimes scream “look at me.”

F: We collect Joe Coleman. He is alive – at least last time we looked. Is he Outsider? The Mandarins who ran the Outsider Show didn’t think so, when they booted him.

Jennifer: So which artists from the contemporary field are you interested in?

A: We don't have any of his work, but I would love to own something by Grayson Perry. I think he is crazy talented, is fearless, works in different media and his cross-dressing is part of the satiric boundary-blurring that drives his transgressivity. His paintings also have an Outsider vibe in their chaotic sprawl, but are anything but.

Morton Bartlett, Standing Boy

5. Do you ever loan pieces out from your collection to other shows? And are there any plans for you to do a showcase just of your collection anywhere?

F: We do loan pieces out. It’s a responsibility.

A: We have loaned several Joe Coleman paintings. One came back with a slight damage to the frame and he came to our place and repaired it. That’s something you wouldn’t trust to TaskRabbit. We have one of the Morton Bartlett boy figures, there are only two, so we have lent that. We’ve also made some of Bartlett’s photos and a Ramirez available.

F: There is an increasingly level of interest in the category. As the arbitrary barriers break down, and auction records for Traylor and Darger shatter the ceiling, museums that were not interested in the material before are increasingly de-snobbified.

A: I would be interested to mount a virtual show, given the way the quarantine has opened the door to new, virtual viewing experiences. There are interesting new technologies like ARTMYN, which deliver immersive experiences using sophisticated digitization that could open up a new world, where collectors could make their works universally available like never before. A new kind of peer-to-peer viewing experience.

F: That is the future. Any takers?

Jennifer: Love that!

6. What style of work, if any, is of particular interest to you within this field? (for example is it embroidery, drawing, sculpture, and so on)

A: As we said, it is less the particular style or form, and more the underlying psychic energy, however it might be expressed.

F: We even have a moneybox and a cigar box, which were created by Felipe Jesus Consalvos for his own use. Sadly, his money box wasn’t filled with the sums that would be available to him today.

A: He was a cigar roller, who worked in weird zone between Dadaist montage and decoupage. His entire body of work was dependent on the holding power of Lepage’s glue.

F: Also in the three-dimensional world, we have several works by the Philadelphia Wireman. That’s his handle because no one knows his name; he lived on the streets of Philadelphia and wrestled found objects into Freudian shapes. His body of work was essentially discovered by Fleisher/Ollman, in the same way that Edward Deeds was first identified by Harris Diamant: the art found its way to the right curatorial hands, although the journey was crazily fortuitous.

A: The Wireman created something totemic out of urban detritus. His work reflects his own despairing sense of self. It wasn’t clever commentary like a contemporary’s artist’s use of discarded objects would be. I see them as hard versions of Judith Scott’s softer, tactile works; found objects that lack representational grounding.

Drossos P. Skyllas (1912-1973), A Pair of Portraits of Pete and Kirtina

7. Would you say you had a favourite artist or piece of work within your collection? And why?

A: You’re not going to make us do that, are you? These artists are neurotic enough as it is, without making anyone feel they are less loved.

F: We were one of the first to buy George Widener when Henry Boxer brought him to the Outsider Art Fair. He continues to invent new narrative modes that channel his obsession with numbers and history and the geometry of time.

A: George has his Titanic period, his Megalopolis period, his Magic Squares period, and other experimental romps. But there is a George-ness that beams through it all.

F: It’s a matter of what speaks to us at different times, in different ways. The explosive energy of Hawkins is full of a crazy organic optimism. He gulps life. Drossos Skyllas is the opposite – he’s not Outsider at first glance, because he’s obviously working in a conventional, painterly vernacular. But there’s a pervasive oddness, beginner flaws in perspective and other basic gaps that collide with intention in a riveting way.

A: We have a pair of portraits over our bed that most people would run from by Skyllas.

F: We can always spend time with Ramirez. Of course, it’s obvious he’s a genius; his mastery of the frame and the way he captures energy and motion, and allows it to interact with the stillness of architectural forms, is uncanny.

A: He created his corpus in the indignity of a mental institution. Yet the work has a quiet and omnipresent dignity. There’s also a magisterial elegance, and whimsy, in Traylor. What can we say about him that hasn’t been said? The more you look at the complexity beneath the minimalism, the more you are rewarded.

F: By the way, there is no whimsy in Ramirez, which speaks to the difference between their lives. Traylor lived in the world and breathed in all its humor and ironies and complexities – including the relationships between men and women, embodied in the repeating, pointing-woman-figure. Ramirez lived in an irony-free mental institution.

We must call out Joe Coleman. He’s a friend and a pure genius. We also are seduced by Dellshau and Yoakum and another Columbus Ohio artist – like Hawkins – Morris Ben Newman. A new gallery called Venus Over Manhattan recently held an all-Yoakum show. It was revelatory.

A: Favorites change at different times based on the emotional climate. Great art is not static. So the pandemic draws you to the Gugging artists who are dealing with their own demons, entrapment, and overwhelming uncertainties.

F: We have some works by Johann Fischer and Leopold Strobl and Gunther Schutzenhoefer, which seem well suited to today’s shapeless anxieties. We bought Leopold and Gunther from our pal Frank Maresca; Ricco/Maresca represents both, and each are tidily brilliant.

Leopold Strobl. Untitled, 2014. Graphite and colored pencils on newsprint cut and mounted on paper. 3.1" x 3.8". Courtesy of Ricco/Maresca Gallery

8. Is there an exhibition in this field of art that you have felt has been particularly important? And why?

A: There have been so many important shows over the years; it’s hard to single one out.

F: It was before our time, obviously – I hope obviously – but the Edmonson show at MOMA was the first time that Outsider was granted stature as a co-equal domain of creative and artistic excellence.

A: And it was the first one-man show of an African-American artist. But in the 50’s and 60’s, Edmonson kind of fell off the map, was relegated to “folk art” as the art world became one-dimensionally focused on abstract expressionism.

I don’t know if you would call it an exhibition, but what Sandy Smith did by creating and promoting the Outsider Art Fair was critical to legitimizing this material and catapulting it onto the public’s consciousness as more than the quaint sentimentality of Grandma Moses.

F: Not that there’s anything wrong with quaint sentimentality.

A: Sandy brought the category to the attention of Roberta Smith and others, and attracted talented and visionary dealers. Some of the major discoveries of the last few decades were introduced there, like when Marion Harris unveiled Morton Bartlett, and the Crist Gallery showed James Castle.

F: The Fair is now in the hands of Andrew Edlin. I thought it was very bold of him, as a dealer – and by the way, he is a friend and we’ve bought from him – to take over the show. And he’s done a great job of injecting relevance, quality and media attention. And bringing in younger collectors, which is the lifeblood of any field.

A: We were in Paris last year and got to see a wonderful exhibition at Musee Maillol that featured French self-taught artists like Rousseau, Bombois and Bauchant. The French love this stuff for its primitive viscerality. It flattens perspective and opens sensibility at the same time.

F: The show presented the convergence of the French aesthetic and culture, and the psychological dynamism of Outsiders, resulting in some massively compelling work. We have a Bauchant portrait of the French aviator Jean Mermoz that is striking as hell.

A: The Traylor show at the Smithsonian was crucial and astounding. To see the extent of his output, and to consider it in the context of the conditions he worked in, was quite moving. And ironic, to see it in the august formality of that setting. Where was the art establishment when Traylor was sleeping in the back room of an undertaker’s establishment?

Charles A.A. Dellschau, Plate 4329 LONGTOUR AEROCOD, 1919, watercolor pencil and collage on paper, 16 x 16.5 inches. Image courtesy of Stephen Romano Gallery

9. Are there any people within this field that you feel have been particularly important to pave the way for where the field is at now?

F: There are some hugely important figures. We spoke about Andrew Edlin, who is a superb dealer and evangelist. Frank Maresca has been pioneering, advocating and codifying this work through books and seminal shows for three decades. He represents the Ramirez estate, what better validation is that? And Frank is still making discoveries and building reputations, like Renaldo Kuhler and Domingo Guccione. Carl Hammer in Chicago, Henry Boxer in London, and Duff Lindsay – who is doing great work in Columbus, Ohio - they have all made significant contributions.

A: Henry has a wise eye; he was the first to bring George Widener to the Outsider Art Fair, and he introduced the world to William Hall, who spent two decades homeless and lived in his car for half of them. We are privileged to have some of William’s works; in them, the car, far from being a prison, is rendered with transcendent, fairy-tale fantasy and virtuosity.

Of course there is wonderful Stephen Romano, who introduced us to Dellschau – he wrote a brilliant book on him – and has championed the work of Mortenson with enormous dedication. Our dear friend Marion Harris, who introduced us to the field and – as we mentioned – also introduced the field to Morton Bartlett. She had the impeccable eye to spot what was almost his entire oeuvre in a booth at the Pier Show. Drawn by its ineffable power, without knowing anything about him, she swept the booth clean and then set about to research Bartlett’s entire life. She published a book, and sherpa’ed one of the true greats to the status he deserves.

A: And then there are those who were so early that credit passed them by. The Ed Sherbyn Gallery had an exhibit of Yoakum in Chicago in 1968. That took guts and vision.

F: Of course there’s James Brett, who has been in hot pursuit of everything context-scrambling and gutsily authentic for decades. He has been an essential force.

A: That’s why his whimsically yet ambitiously named “The Museum of Everything” – and now “The Gallery of Everything” - are so apt. Of course it’s not literally everything, but to James it’s everything that matters, and to the artist, it’s everything lodged between their ears. Their artistic world is their everything.

F: If we left out anybody, please don’t hold it against us. Extend that collector’ discount, to assure you’ll be name-checked next time! Oh yeah, there’s Kerry Schuss, we bought an intimate Birnbaum self-portrait – with his wife - from Kerry. Steven Powers has a far-ranging, but thematically coherent sensibility; we absolutely love the Ray Materson we acquired from him, which has deadpan irreverence. And Galerie St. Etienne, who was there at the creation, and was an agent of genesis. We bought a luminous Jakob Radler from them.

10. Where would you say you buy most of your work from: galleries, a studio, art fairs, exhibitions, auctions, or direct from artists?

A: A combination of auctions, shows, websites, and of course, dealers directly. Less from the artists themselves, as it’s not really a practical opportunity given that dealers work hard to shut down private access.

F: I think that’s okay, though. It protects the artists, many of whom are fragile.

A: Yeah. While there is something appealing about having a whiskey at 11am with an artist on a front porch in Mississippi, artists need ethical and reputable dealers to protect and advance their interests.

Ray Materson. Public School Girls, ca. 1994. Unraveled socks. 12" x 14"

11. A conflicted term at present, but can you tell us about your opinion of the term outsider art, how you feel about it and if there are any other words that you think we should be using instead?

F: I happen to love it, I think it’s great. I know it’s embroiled in controversy – scholarly and otherwise - but I am quite delighted with the term. It feels accurate when the words pass your lips. One of the things we do in our business is name things and if I had to name this complex and noisy field, that probably would have been on my top ten list.

A: When we debate Outsider versus self-taught versus visionary vs Art Brut, it’s an argument about a continuum. Is Joe Coleman banished from the definitional house because he took one art course? Dubuffet said that these artists were “uncooked by culture”, and that works for me.

F: It’s a great phrase because it recognizes the idea of being in one’s own bubble.

A: Actually, Joe Coleman may not be uncooked, more like parboiled. A similar framework came from Hans Prinzhorn, the psychiatrist who studied the art of the mentally ill in the twenties – he said they were unscathed by trends. That lets the Gugging artists, along with Castle, Dellschau and the under-rated Dwight Mackintosh through the door.

F: You end up in a reductionist spiral that isn’t useful or helpful. I mean, you can have a Talmudic discussion about whether creating with an eye towards selling, a capitalist outcome, eliminates you as an Outsider. That would discount Traylor. Who would credibly argue for that? His work is purely a brain-to-paper journey, not concerned about marketability. But he sold it.

A: If you peel it back and peel it back again and if you are going to be super-fundamentalist about this, be an Outsider art jihadist, you would only fully accept people who are locked in emotionally, who have no idea of the world around them, which I think is an unnaturally limiting, narrow – and ultimately damaging - definition of this field.

F: There are many who can be on the outside looking in, distanced from the art industrial complex.

A: When I see an outsider artist who has a website, though, I get suspicious immediately. But lots have them, so I need to let go of that bias.

Joe Coleman, Albert Hicks

12.Have you managed to persuade many friends to become interested in this field and what do they make of the art in your collection?

F: No. Zero success there. They all come here and wonder what is wrong with us. These are our non-collecting friends. You see them observe and the eye rolling is palpable, if not visible. One time we took a friend of ours who is a psychologist, and unfamiliar with the field, to the Pier Show, thinking she would deeply appreciate it. She did, because she could look at the art through a trained eye. It was fun to watch her react in real-time, to the first time.

A: It is very much like the reaction to non-objective art in the 50’s and 60’s. There were these cartoons in the New Yorker back then with people looking at a Mark Rothko or Kenneth Nolan and a caption that said “My kid could do that.” And people say that sort of thing about outsider art - they look at it and they don’t understand what’s operating there, the mix of simple and sophisticated that is literally outside their structure of what normative art should be.

13.Is there anything else that you would like to add?

F: It’s a wonderful thing to collect. For us, it’s not just collecting the art, but also collecting the people that are involved in it – that includes the artists and the dealers. It is a wonderful, fascinating and enriching experience.

A: I agree and in a world that is increasingly fake and affected, the authenticity and the immediate connection to the artists and the work is more important than ever. I’ve been blogging about living with the intensity of this art-to-brain synapse during the pandemic’s for Frank’s website. Contemporary art is and always has been a marketing platform, but it has become even more so. It is very manipulative. The artists have become so self- aware and so self-conscious, so much playing to an audience and playing to a critical audience, that much of it has lost any emotional weight as a result.

F: The cross-over phenomenon is real. Just look at Yoakum, who has been featured and collected by Venus over Manhattan. I worry, though, about gazillionaire dealers coming in and dominating the field. It’s the equivalent of gentrification in the art world.

A: Yes for sure. The pandemic is changing the entire art world; we are seeing a consolidation in bigger galleries and their inventories. Dealers are marketers, and marketers look for new opportunities. Even the most expensive outsider artists are still decimal points removed from the most expensive contemporary figures. This work is still way undervalued in this way, which is not what draws us to it.

F: Back in the early days, dealers and collectors would load up their cars and haul down back roads in search of the next Traylor or Purvis Young or Finster who whoever. It was the artistic equivalent of what happened with American blues music, when Alan Lomax from Folk Ways Records, tracked down old blues men and recorded them. That’s still the dream. To find decades of sequestered genius.

A: Yeah, But it’s random. When this private work is revealed to the public, it’s a thrilling moment.

F: Yes, and predatory collectors are always waiting. So I guess that’s everything for now, as we could talk forever.

A: We could and did.

Martín Ramírez, Untitled (Man at Desk), ca. 1960-63, Gouache and graphite on pieced paper. Courtesy of Ricco/Maresca Gallery